Since the first predecessors of the American people stepped on Jamestown, Virginia, they brought with them a revolutionary ideology of “city upon a hill.” Over a history of 400 years, American society matured this into a national ethos known as the “American Dream.” As an idea of limitless opportunity and prosperity for those who committed their efforts to achieve their dream, this ideology has shaped the fundamental societal framework for the United States. The Great Gatsby, despite being referred to as a masterpiece reflecting the Jazz Age during the Roaring Twenties, it is actually a critical reflection of the American Dream by F. Scott Fitzgerald. Through the stories of futile efforts of Gatsby in achieving his self-conceptual life, Nick’s rejection of NYC- an iconic symbol of the American Dream’s opportunities, and the Wilsons’ bitter destiny, The Great Gatsby depicts the demise of the American Dream in the Roaring Twenties. This demise of the Dream is expressed through three aspects: its fundamental limitation, its duality of opportunities and equalities, and its exclusive alignment to materialism.

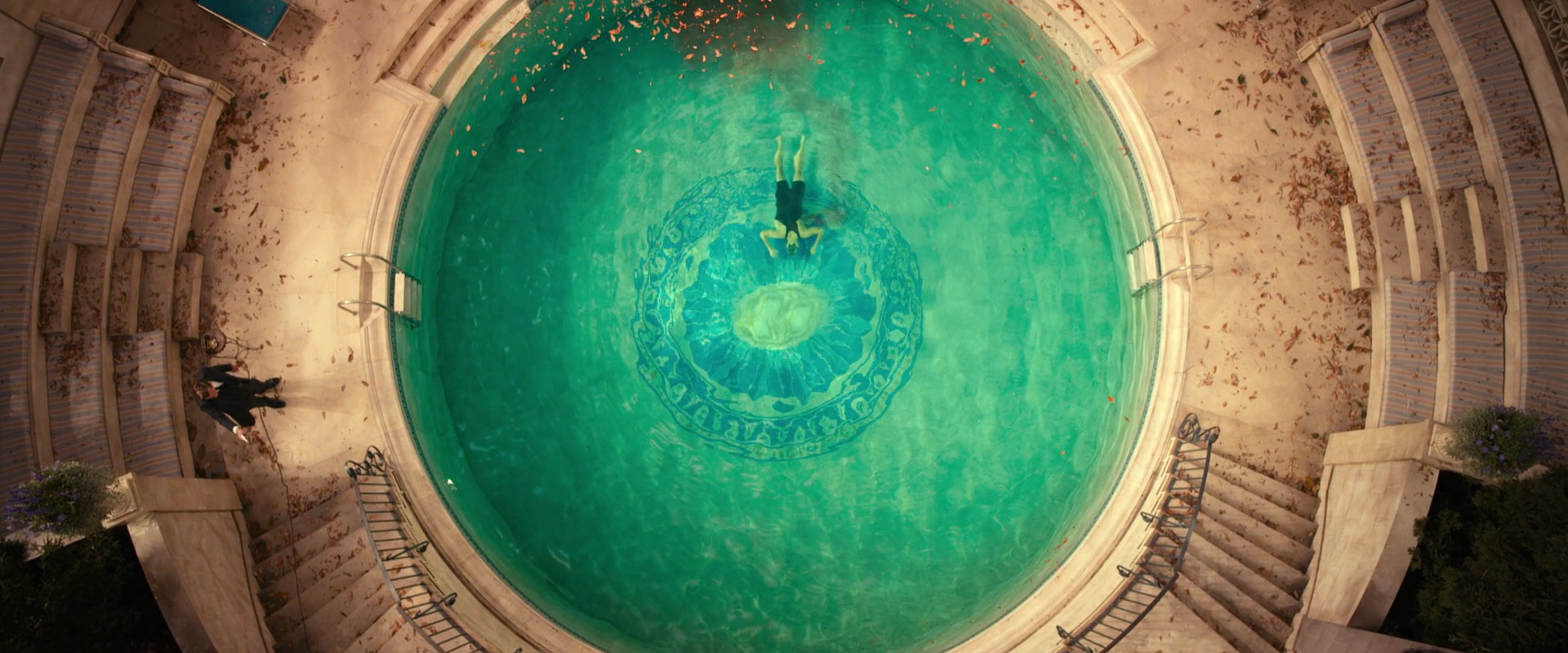

Firstly, Gatsby’s failure to integrate into the aristocratic elite class and possess Daisy depicts the fundamental limitation of the American Dream since the early days of America. In an op-ed for the Modern Age academic journal published in 2007, John A. Pidgeon emphasized the significance of the influences of Puritanism and Calvinism doctrines in the American Dream. According to Pidgeon, since the arrival of the first Europeans in the American Continent, “Doctrine of the Elect” has played an essential role in the function of the society. “… [A]lways in the background is the belief that the only truly worthy achievement is that leading to material gain” (Pidgeon 179). Jay Gatsby tried to achieve massive wealth, for the sake of gaining admission to “the Elect” class. As Pidgeon concluded, “since hard work was associated with God, and since hard work often resulted in wealth, […] wealth came to be a sign of goodness since it indicated membership in the Elect” (Pidgeon 178). However, he never really integrates successfully in this aristocratic class, as seen from the fact that he was almost alone all the time in his own magnificent parties. All the interactions with his guest appeared to be artificial and shallow. He has a palace full of all elite people of New York City, yet he feels lonely and just needs a single friend- a friend who can hang out or go swimming with.

“Your place looks like the World’s Fair,” I said.

“Does it?” He turned his eyes toward it absently. “I have been glancing into some of the rooms. Let’s go to Coney Island, old sport. In my car.”

“It’s too late.”

“Well, suppose we take a plunge in the swimming-pool? I haven’t made use of it all summer.”

“I’ve got to go to bed.”

“All right.” (Fitzgerald 81)

Since his teenage age, Gatsby built for himself a self-conceptual elite life and his whole life revolves around it. But after all, all those parties, all that immense wealth never made Gatsby a member of “the Elect” class. His origin itself made him “unworthy” to be in the aristocratic class, despite how hard he tries to climb up the social ladder. Thus, Gatsby is particularly sensitive and humiliated about his identity. Pidgeon supposed “[t]he scene in which Gatsby shows his pile of shirts to Daisy is not vulgar but pathetic” because he wants “to show her that he has been “cured” of poverty,” not “out of vanity or pride, but in humility and reverence” (Pidgeon 180). This angle of analysis of Pidgeon once again reinforces the idea of the “unworthiness” Gatsby is feeling. Due to his inferior origin, in order to possess Daisy- a typical individual of “the Elect” class, Gatsby has to display his eligibility in an awkward and humiliating way. This limitation of the American Dream, as aforementioned, originates itself to the very first days of America, with the notion of Puritanism and Calvinism that a “worthy” one is predetermined by God. Furthermore, Pidgeon supposes that “[i]n the end, Gatsby’s insistence on maintaining the dream kills him.” “It is obvious that Gatsby is aware that Wilson will come to kill him. He can run away, but he chooses to stay because he really prefers to die rather than face up to the fact that his dream was not worthy of him” (Pidgeon 181). Pidgeon depicts that Gatsby’ rejection to confront reality and insistence on living with his delusional dream kills him. He is fully aware of the threat to his own life but refuses to run away, just for a hope that Daisy will call him and they will leave and live happily together. His whole life revolves around achieving his dream since every single decision he ever made is to bring his ideal self-conceptual life come true. It is his obsession with the possibility that his own version of the American Dream might come true that led to his tragic death. This aspect of Gatsby’s motivation depicts the desperation of American people in believing their ability to achieve the dream. Although Gatsby’s death due to his obsession with the dream is an extreme and symbolic exaggeration of this notion, Fitzgerald wants American people to be aware of their delusional belief in the American Dream. In a nutshell, the American societal and philosophical fundamentals during the Roaring Twenties were still heavily influenced by the notion of “the worthy,” “the elect,” “Social Darwinism,” originated from the very beginning of America itself. By analyzing Gatsby’s failure to gain acceptance into the aristocratic class of “the Elect,” his sophisticated yet futile efforts in possessing Daisy and his own death due to this delusional obsession, we understand the limitation of the American Dream during this era.

Secondly, throughout the book, Fitzgerald wants to correct the misconceptions of the American Dream. It is a paradox of reality and idealism, which depicts the struggle of the American nation to fulfill the dream of its citizen as promised in its national ethos. The prospect of an equal opportunity for all to achieve his/her dream in the 1920s is challenged by Fitzgerald’s depiction of the duality of the American Dream. Many literary critics, such as Kimberley Hearne, an Arizona-based critic for The Explicator academic journal, attempt to analyze this angle of the book. In a featured article on the journal in August 2010, Hearne analyzes the connection between the language and philosophy of The Great Gatsby with Fitzgerald’s attempt to correct the misconception of the American Dream. “For Fitzgerald, the American Dream is beautiful yet grotesquely flawed and distorted. No matter what idyllic picture we paint of America and all of its promise, underneath the brightest of hues lies the stark white canvas of truth: No one is truly equal…” (Hearne 191). Hearne believes that The Great Gatsby is a depiction of the inequality of the American society in the Roaring Twenties. Amid the 1920s where fundamental conflicts of social classes, races, nationalities played a key role, The Great Gatsby symbolizes these inequalities into a storyline with individual characters representing different classes of American society. As Terry Doran said, “[a]ll men may be created equal, but some are more equal than others,” the analysis of Hearne re-emphasized that the American Dream may be exclusive for “worthy” and “elected” people of the elite class at the very beginning. It is just not feasible for an average, middle-class or working-class American to climb up the social ladder and truly integrate into a new life. Notwithstanding Gatsby’s immense efforts and hard work, he never achieved the self-conceptual life he always dreamed for. Regardless of Nick’s firm belief in the opportunities of NYC’s Wall Street in the first days, he realized an empty, grotesque mechanism underneath it. This duality of opportunity and quality via the story of the Wilsons is obvious. George Wilson, throughout the book, is pictured as a hard-working man trying his best with the garage business. Myrtle’s affairs with Tom Buchannan depicts her desperation for materialism and societal status. However, their fate is predetermined to be futile, which is similar to that of the working-class people in the Valley of Ashes- an iconic symbol of the inequality of American society in the Roaring Twenties. “Myrtle certainly has access to some of the “finer things” through Tom but has to deal with his abuse, while George is unable to leave his current life and move West since he doesn’t have the funds available. He even has to make himself servile to Tom in an attempt to get Tom to sell his car, a fact that could even cause him to overlook the evidence of his wife’s affair” (Wulick). On the other hand, the “old money” elite people like “Tom, who dragged Myrtle into an increasingly dangerous situation, and Daisy, who killed her, don’t face any consequences” (Wulick). The American Dream, after all, is depicted by Fitzgerald as a duality due to its exclusiveness for “the Elect” and rejection of “the poor working-class” who are not predetermined to have a place in the upward trajectory of this dream.

Thirdly, Fitzgerald depicts the American Dream during this era as a merely shallow alignment to materialism. The Dream altered itself from the concept of equality for everyone to achieve “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” as rooted in the Declaration of Independence, to the exclusiveness of materialism gain. We are made to believe that Gatsby’s life revolves around Daisy, yet the truth is that it revolves around a symbol of materialism, which is an indication of the American Dream during the Roaring Twenties. In a conversation with Nick in the Buchannan’s Residences, we can witness the validity of this claim:

“She’s got an indiscreet voice,” I remarked, “It’s full of -” I hesitated.

“Her voice is full of money,” he said suddenly.

That it was. (Fitzgerald 120)

Jay Gatsby is obsessed with the American Dream since his teenage, and he fully senses the sounds of “old money” when he hears it. The characteristics of Daisy’s accent and word choices infer of her privileges. Gatsby does not love her but the over-idolized symbol she represents- the indicator of the aristocracy, the worthiness of “the Elect” which all displays itself in the form of materialism. Or as Dr. Wulick said, “Gatsby’s less-than-wealthy past, which not only makes him look like the star of a rags-to-riches story, it makes Gatsby himself seem like someone in pursuit of the American Dream, and for him the personification of that dream is Daisy” (Wulick). With that being said, Gatsby hollowly degrades himself into a corrupted criminal businessman who gains wealth through illegal activities with people like Wolfsheim. Initially, the founding fathers of America intended the dream to be a full-scale spectrum of the fulfilled life of happiness, prosperity and equality, not just the mere pursuit of materialism at all costs. Yet in the Roaring Twenties, a unique era of American history where economics booms took an emphasis in the society, this national ethos aligned itself exclusively to materialism.

In conclusion, The Great Gatsby is a critical reflection of the demise of the American Dream during the Roaring Twenties. Fitzgerald’s mistrust in the dream is expressed through the fundamental limitation of the dream, the duality of opportunities and equality, and the exclusive alignment of the dream to materialism. The tragic stories of Jay Gatsby and the Wilsons through the bitter narration of Nick Carraways are meant as an effort of Fitzgerald to correct the misconception of the American Dream. Ironically, despite claiming its emphasis on social mobility, the Dream itself has always been criticized due to its exclusiveness to particular groups of people. For most of American history, equal opportunity for all people is a luxury. The Declaration of Independence itself reserved the natural rights exclusively for “[white] men,” and the original Constitution did not mention about the rights of women and black slaves at that time. Only until the last decades of the 20th century, the de jure segregation of American people based on races, genders and origins was officially ended with the ratification of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. However, de facto discrimination is still persisted in American society, thus restricting the opportunities and imposing artificial barriers on different groups of Americans. In nowadays society, “[a] lot of Americans think the U.S. has more social mobility than other western industrialized countries [but studies] makes it abundantly clear that we have less: your circumstances at birth—specifically, what your parents do for a living—are an even bigger factor in how far you get in life than we had previously realized” (Hout). After 94 years, Fitzgerald’s critical perspectives of the American Dream is still relevant and expresses fundamental flaws in this national ethos of the United States. After all, the Dream is just “a mirage that entices us to keep moving forward even as we are ceaselessly borne back into the past.”

For the full list of references, visit the original post on my blog The Cosmopolite Guru.