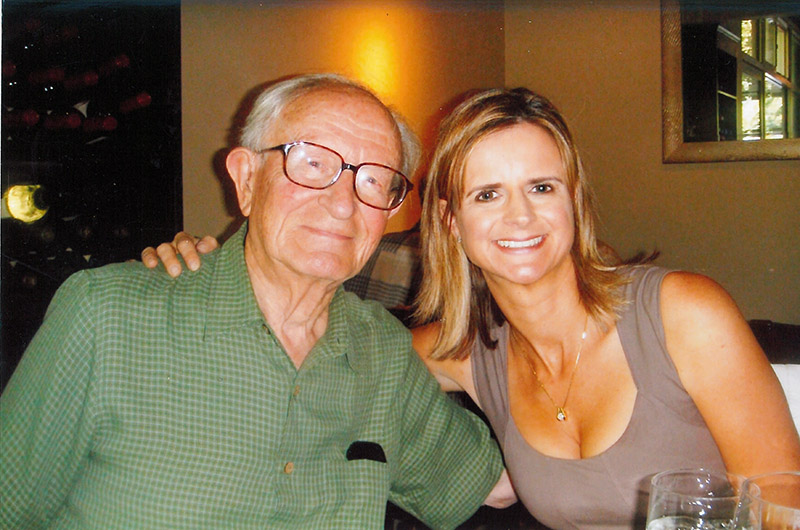

One of my new year’s resolutions this year was to learn another language. I talk to my students about what an advantage it is in today’s global workplace, and yet I can’t call myself bilingual, let alone a multilinguist like my grandfather.

As a child, I used to speak Polish, the language of my immigrant grandparents; but, like many teenagers, I started responding in English during my adolescence. My grandfather spoke nine languages, so it shouldn’t be that hard for me to re-learn one language, right?

Wrong.

Polish is tough, I tell myself. So many different cases and words with different genders. So many consonants piled up right next to one another. I feel like I’m on Wheel of Fortune asking to buy a vowel.

Understanding multiple languages was a matter of survival for my grandfather. Orphaned in Poland at the age of 13, he tutored kids in languages to make enough money to pay for food and shelter as a high schooler living alone with a younger brother. He loved languages so much that he earned a full scholarship to university to become a linguistics teacher. But on the day he arrived for his second year of college, Germany invaded Poland, and World War II began.

As newspapers printed in German started being delivered to Polish farmers, he translated them at the dinner table in exchange for food and shelter. At other times during the war, he would teach Polish to children in secret schools that were punishable by death if discovered. His knowledge of French allowed him to stay alive by translating job instructions to French prisoners-of-war. He even impersonated a Nazi soldier on occasion to escape arrest, as an intellectual on the run.

After the war, my grandfather escaped jail by the Soviet Secret Police and fled to Sweden in search of a better life. Learning another language, Swedish, helped him devise an elaborate plan to become a sailor and return to Poland to smuggle his wife, my grandmother, to Sweden.

Their search for freedom would not end there, as Sweden was not far away enough from the people that wanted to capture my grandfather. Once again, his knowledge of languages would help them survive. While in Sweden, he learned his ninth language, English, so that he would know enough to be able to immigrate to the U.S. and find a job.

My grandfather ordered an English course from the Linguaphone company in Stockholm, and received a set of records and a manual. He bought a Gramophone to listen to the records. When he played the first record, it sounded garbled and impossible to understand. My grandfather wrote a letter to Linguaphone, sending the records back, and requesting a course for beginners, not advanced English learners. They responded that this was indeed a course for beginners, and advised him to listen to each record hundreds of times to get a feel for the language.

My grandfather penciled a mark on a piece of paper each time he listened to the record, while he was cooking, washing, cleaning, or eating. By the time he listened to the record one hundred times, he opened the textbook, and could follow each word, even though he could not understand it yet. After completing fifty lessons, he’d learned the basics of English pretty well, even with correct pronunciation. He was able to use his new knowledge of English to read announcements for U.S. jobs and respond to them. He would later use parts of this method with students when he taught Polish at the Defense Language Institute for thirty-five years.

My grandfather’s method of learning languages was quite different from mine. I have been using a free app on my phone to practice a little each day by reading or listening to sentences in Polish, and typing my responses. I’ve also enlisted the help of Polish friends for practicing pronunciation. Although I seem to be slower to learn another language than my grandfather was, I believe that it will be worth it in the end to be able to build connections with Polish friends and acquaintances. I can remember seeing my grandpa’s face light up when someone asked him if he could speak their particular native language. He would happily respond with a few friendly sentences in their language.

I hope to experience this. When my app sends me a notification that it is time for my daily lesson, I am reminded that my lesson is not just about re-learning my forgotten Polish words. It’s a way to connect with my heritage and honor my grandpa’s extraordinary life.