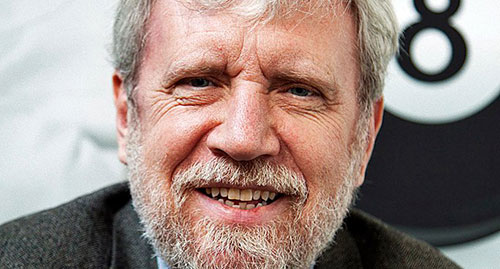

Have you ever thought you’re not cut out to do something due to a lack of talent? Karl Anders Ericsson would disagree and he has the data to prove it. Anders spent 30 years studying people who are exceptional at what they do, and trying to figure out how they got to be so good. His conclusion: in most cases, talent doesn’t matter but deliberate practice does. He and his colleagues provide new research that illustrates that outstanding performance is the outcome of years of measured or deliberate practice and coaching and not of any innate talent or skill. Ericsson, psychologist and author of “Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise”, has dedicated his career to understanding how people become exceptional within one field. I was so lucky to have interviewed him in 2019. He was very talented and a kind soul. I hope you enjoy this interview.

Could you tell us about yourself? At a very early point in my life, I found that I could improve my performance. I read biographies that focused on how people succeeded and tried to understand how and why and get into their mindset. Even a genius like Mozart had to work for at least ten years before producing something recognised as a masterpiece.

Take us back to the beginning. How did your research begin about being an expert? I have never seen an individual whose excellence was not the result of formal training. I had a lot of push back about that but all achievement we see is, in fact, the product of extended deliberate practice. I have yet to find attributes that cannot be influenced by training. Anyone can build proficiency in any field. The only reason most of us don’t build expertise is lack of the single-minded focus required to engage in deliberate practice over years

What is involved in deliberate practice? Deliberate practice is a specialised–and particularly effective–form of purposeful practice: An experienced teacher or coach designs the training exercises and monitors a student’s progress, modifying the training as necessary to keep the student progressing steadily. Anyone can apply these same methods on the job. Say you have someone in your company who is a masterly communicator, and you learn that he is going to give a talk to a unit that will be laying off workers. Sit down and write your own speech, and then compare his actual speech with what you wrote. Observe the reactions to his talk and imagine what the reactions would be to yours. Each time you can generate by yourself decisions, interactions, or speeches that match those of people who excel, you move one step closer to reaching the level of an expert performer. Simple practice isn’t enough to rapidly gain skills.

“Living in a cave does not make you a geologist. Not all practice makes perfect. You need a particular kind of practice, a deliberate practice — to develop expertise.”

How can this be applied to the work setting? This kind of deliberate practice can be adapted to developing business and leadership expertise. The classic example is the case method taught by many business schools, which presents students with real-life situations that require action. Because the eventual outcomes of those situations are known, the students can immediately judge the merits of their proposed solutions. In this way, they can practise making decisions 10 to 20 times a week.

In your opinion what is the path to true greatness? The crucial element is an awareness of what it takes to become an expert and, therefore, you are better equipped to maintain the deliberate practice essential to construct new skills. I don’t deny that genetic limitations, such as those on height and body size, can constrain expert performance in areas like athletics. However, I believe there is no good evidence so far that proves that genetic factors related to intelligence or other brain attributes matter when it comes to less physically driven pursuits.

What is the best piece of advice you were ever given? Bill Chase, (American trumpeter and leader of the jazz-rock band Chase), once said, “To be successful, you have to be the best in the world at something and that something can be very small.”

What’s the next challenge for us? If everybody were concerned about improving our world, our world would benefit so much. Once people retire, they can do so much for the younger generation; their experience, expertise, and knowledge are valuable and essential for youngsters.

“So, ask yourself about your impact on people and what you can do. That’s my mantra.“

What’s next for you? I want to continue to make a positive impact on someone outside myself. My parents were religious, and serving others and doing good were crucial to my upbringing. I was fortunate enough to meet the Dalai Lama, and his commitment to wanting happiness and ending suffering is remarkable.

So, ask yourself about your impact on people and what you can do. That’s my mantra.

Reference: Peak Secrets from the New Science of Expertise by Anders Ericsson and Robert Pool