Like many modern women married to modern men, I was blindsided by the amount of childcare labor that defaulted to me once my husband and I — both full-time therapists — had kids. In our home, no amount of discussion (and that’s the polite word) tipped the scales. I decided to use my research and reporting skills to answer what became the burning question of my early years of motherhood: why do women who work outside the home continue to do so much more unpaid labor in it? Here is what I learned:

1. It wasn’t just me. I understood before I began my research that many women I knew were in the same predicament. I didn’t know how strongly empirical evidence validated our mutual subjective experience. According to Pew Research, 63 percent of full-time working mothers report that they do more to manage their children’s lives than their husbands. Since the turn of the millennium, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has consistently found that women who work full-time take on about 65 percent of their household’s childcare labor. Fathers of babies engage in about twice as much leisure time on weekends as their female partners. Working mothers are 2.5 times as likely as working fathers to get up in the middle of the night with their preschool-aged children. I could go on (and on), but I have a word limit.

2. A mother’s anger about inequity tanks marital happiness. Sociologists find that a male partner’s contribution to childcare is the most important factor predicting relationship conflict and mothers’ satisfaction. Women who report that they do more childcare than their husbands are 45 percent less likely to describe their marriages as “very happy” than women who say responsibilities are shared. Studies in the last decade in the UK, Sweden and the United States have all found that couples with low levels of male partner participation in domestic chores are more likely to separate than couples in which men do more. As satisfaction with a male partner’s involvement with childcare increases, so to do positive marital interactions, closeness, affirmation and positive affect. As it decreases, thoughts of divorce, negative affect and depression go up—for mothers. Although perceived unfairness predicts both unhappiness and distress for women, it predicts neither for men, who often do not seem to fully register the problem.

3. This has next to nothing to do with biology. Fathers, like mothers, are actually biologically-primed for parenthood. Throughout the prenatal period, men in close contact with pregnant partners undergo physiological changes. Though lesser in degree, expectant fathers experience a rise in the levels of the pregnancy-related hormones prolactin, cortisol, and estrogen in proportion to that of their baby’s mother. Additionally, testosterone, associated with competition for mates, declines. Second-time fathers produce even more prolactin and less testosterone in the company of a pregnant partner than do first-timers.

4. Mothers feel a lot of social pressure around parenting, and fathers don’t. The ideology of “intensive mothering”—a term coined by sociologist Sharon Hays in the late 1990s to describe the parenting ethos of the day—mandates: the best mothers always put their kids’ needs before their own, the best mothers are the main caregivers, the best mothers make kids the center of their universe. Hays defines intensive mothering as a gendered model of child rearing that is child-centered, expert-guided, emotionally absorbing, and labor-intensive. In her interviews with women, Hays found that no mother is spared this mandate, no matter her age or race or class or ethnicity. Fathers are lauded for showing up. Mothers are criticized for failing to meet intensive mothering’s impossible standards.

5. Boys are not raised to consider the needs of others all of the time. From the cradle, girls gain positive regard by behaving in feminine ways that signal accommodation, while boys earn praise for behaving in masculine ones that signal assertiveness. As they grow, boys learn to do for and think of themselves (behaving “agentically”), while girls learn to do for and think of others (behaving “communally”). Women’s self-reported feelings of agency have increased on a dramatic slope over the last decades as women have equaled and even surpassed men in earnings and education; men’s self-reports of communality have remained stagnant.

6. Men may just be ready to step up. When an op-ed I wrote for the New York Times went viral a couple weeks ago (What ‘Good’ Dads Get Away With), I expected the angry comments I got from men detailing all the yard work and automotive repairs that apparently occupy so much of their time. What I did not foresee were the e-mails and Tweets from men who spoke of seeing themselves reflected in the not-doing-their-share fathers I interviewed for the article — men who felt ready to make a change. “People are always telling me what a good father I am,” wrote one dad, “It’s always uncomfortable for me because in the back of my head I know I do so much less than my wife. Thanks for articulating this for me, and helping me to think about what I can do to contribute more.”

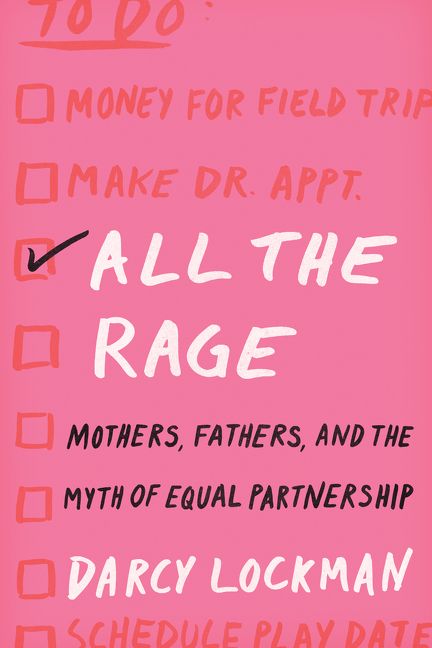

For more information on this topic, read Darcy Lockman’s newly published book, All the Rage: Mothers, Fathers, and the Myth of Equal Partnership

Follow us here and subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

Stay up to date or catch-up on all our podcasts with Arianna Huffington here.