In part 1 of this series, I shared my first draft at defining “empathy” as follows:

Empathy is a word invented to explain our potential to move from:

https://community.thriveglobal.com/stories/empathy-is-an-explanation/

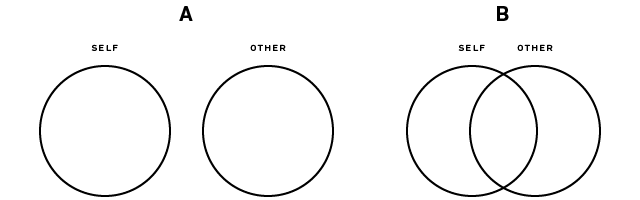

A. Feeling separate from an “other” to

B. Feeling one with them.

This definition will evolve in this article. So please stay tuned.

The Importance of Definitions

To be clear, I’m not defining “empathy” to claim authority over it.

“Then why are you doing it?” You may ask.

First of all, to reduce misunderstandings.

In Chinese, the character for “name (名)” is made of two characters 夕 and 口. The top character depicts the moon (夕) and connotes “night.” The lower character depicts a mouth (口) and connotes “to make a sound.” One interpretation of the character for “name (名)” is that when it gets dark outside, you have to say your name out loud so others can know who you are. The implication is that when it’s bright outside, we can see each other, thus a name is no longer necessary for recognition.

I feel the same way about defining words.

As I write this article, I’m imagining two people in the dark. One is you, the reader. The other is me, the writer. I’m in the dark on how you, the reader, define the word “empathy.”[1] I’m choosing to say my definition out loud in hopes that at least you know what I’m talking about.

To illustrate how easily misunderstandings can arise, let me show my definition of empathy with a graphic aide.

Empathy is a word invented to explain our potential to move from A to B.

When I ask people to point out any new information they have gathered from this graphic aide, some people say that they had imagined B to be one circle instead of two. Why? Because I had used the word “one” in my definition. That’s a reasonable assumption. Yet, what I had intended to communicate was two circles becoming one chain. Not two circles becoming one circle.

Having learned of this possibility of misunderstanding, I have since revised my definition as follows.

Empathy is a word invented to explain our potential to move from:

A. Feeling disconnected or separate from an “other” to

B. Feeling connected as one with them.

Going Beyond Agreeing to Disagree

The second reason why I have defined the word “empathy” is to take us beyond agreeing to disagree.

For example, I have often heard two people arguing in the following way, unable to go beyond agreeing to disagree.

Person 1: Empathy promotes bias!

Person 2: No, empathy helps us overcome bias!

How is it that one person says empathy can promote bias, while another person says empathy can help us overcome bias?

This makes no sense.

It’s impossible.

A paradox!

Except… This is very much possible when people use the word “empathy” to mean both an experience and an explanation of why such experience is possible. In other words, the moment we make a distinction between an experience and anexplanationof why that experience is possible, this paradox will be dissolved.

Let me explain.

Part of what Person 1 is saying is that it’s possible that we feel connected as one with someone while simultaneously feeling disconnected from someone else. If you’ve ever taken sides in an argument, you know this to be true. Not only that, but if we stay that way, it is also true that we may end up promoting a bias toward one person at the expense of another. This means Person 1 is right.

At the same time, what’s important to note here is that what Person 2 is talking about is the experience of coming to feel connected as one with someone. In particular, someone whom we previously did not. In other words, we’re not actually talking about empathy, since we defined empathy as an explanation, not an experience.

Then, what if we gave the experience of feeling connected as one a different name, like “empathizing”as opposed to empathy? While we’re at it, we can also label the experience of feeling disconnected or separate from an “other,” as “not empathizing.”

Once we do this, we can say that if we empathize with one person and not others, we may promote a bias. At the same time, since empathy is an explanation of our potential to move from not empathizing to empathizing, if we can develop greater empathy, then we can come to empathize with people with whom we currently do notempathize. Thus, empathy can indeed help us overcome our biases. This means Person 2 is also right.

Paradox dissolved.

Having learned about the frequency of such unproductive conversations, I have since revised my previous definition of “empathy” as follows to include both “empathizing” and “notempathizing.”

Empathy is a word invented to explain our potential to move from:

A. Not Empathizing: Feeling disconnected or separate from an “other” to

B. Empathizing: Feeling connected as one with them.

Becoming a Scientist of Empathy

My final reason for defining the word “empathy,” is to support our individual pursuit of a more in-depth understanding of empathy. Actually, this is less a reason for defining the word “empathy,” and more a reason for making a distinction between “empathy,” which is an explanation, and “empathizing” or “notempathizing,” which are experiences.

Basically, experiences allow us to acquire empirical evidence. In other words, we can know for ourselves when we feel connected as “one” with an “other.” We can also know when we do not. Now, if we were to ask why such an experience is possible, we could say “because of empathy.” After all, that’s what the word was invented to do: explain our potential to move from not empathizing to empathizing. At the same time, it’s just a word. It doesn’t actually explain anything. So to fill that gap, we have many guesses or hypotheses.

For example, you may have felt disconnected from someone who said or did something that, to you, seemed stupid. But after you appreciated their situation, their needs, and the thought process they used to navigate their situation to fulfill their needs, you may have felt connected as one with them. Based on this observation, you can come up with a hypothesis that says “To move from not empathizing to empathizing, we need to see things from that other person’s perspective.” This is one hypothesis often associated with how empathy works.

On the other hand, you may have also had an experience where you felt connected as one with someone, yet you did not see anything from their perspective. Instead, it was something about the way they listened to you that helped you feel connected as one with them. Based on this observation, you may come up with another hypothesis that says “To move from not empathizing to empathizing with someone, we need to be listened to by them in a particular way.” This is another hypothesis often associated with how empathy works.

How about another one? You may have taken a mime class, where you felt connected as one with another person while mirroring their behavior. Here, there was no seeing from their perspective or even being listened to in a particular way. Based on this observation, you may come up with yet another hypothesis that says “To move from not empathizing to empathizing, we need to mirror their behavior.” This is also a hypothesis often associated with how empathy works.

The list goes on.

In fact, I invite you to come up with as many hypotheses as you’d like. I also invite you to test them in different situations and discuss your findings with others doing the same thing. You may learn that there are different ways to hypothesize about the same observations you’ve made.

This is why I believe the distinction between empathy and empathizing can support our individual pursuit of a more in-depth understanding of empathy.

With the distinction between empathy and empathizing in place, we no longer have to take other people’s opinions on what empathy is as the gospel. We can think and decide for ourselves through experimentation. As physicist Richard Feynman once said,

I believe a provision of such a simple framework that empowers us to pursue a more in-depth understanding of empathy will make a significant difference in reflecting on the 3 questions I had set forth at the beginning of this series.

- What does it mean to thrive together?

- Why does it matter to be together?

- How can we thrive together?

Stay tuned for Part 3.

[1] Batson, Daniel. “These Things Called Empathy: Eight Related But Distinct Phenomena.” In The Social Neuroscience of Empathy. Edited by Jean Decety and William John Ickes. Cambridge, MA: MIT press, 2009. 3–15. 4.