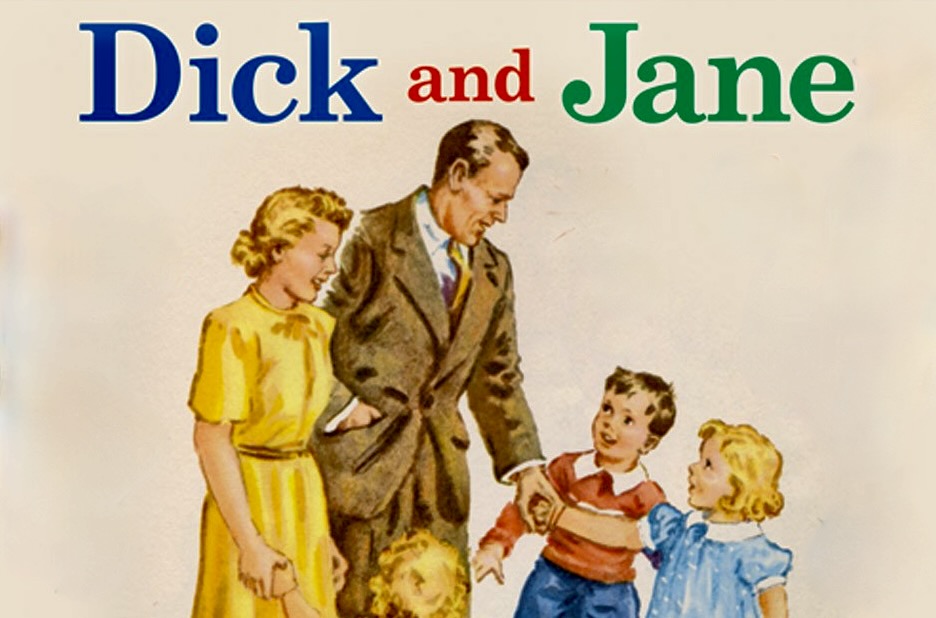

I was born in 1950, the youngest of five children in a white, working-class family living in a predominately blue-collar neighborhood in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. There were not many books in my household, but I distinctly remember the “Dick and Jane” series, which were the school textbooks that were used to teach reading, back in the day. And I definitely remember the illustrations and how the families in those books were portrayed.

Television shows like “Father Knows Best,” “The Donna Reed Show,” and “Ozzie and Harriet“reinforced a father’s image, always dressed in a suit and tie, which was not a common sight in my community. I remember asking my mother why my father or any of the dads we knew didn’t dress like the fathers represented in those books or on the TV shows we watched.

I have heard from friends who are Black describe what happened in their homes during that same time period when a person of color appeared on television… everyone in the family would excitedly come running to witness this rare occurrence.

These anecdotes illustrate a child’s natural inclination to look for a reflection of themselves in the world around them. This is what representation – or the portrayal of a person or group in books and other media – is all about.

And it matters!

Children need to see themselves included and represented, and that representation should be truthful and not based on stereotypes. How people are depicted shapes how they see themselves and how others see them. It also defines or limits possibilities that one can aspire to depending on whether the representation is positive or negative.

For those readers who responded to my recent blog: Should We Continue To Celebrate Dr. Seuss? with a “don’t like it, don’t read it” reaction, I would counter that continuing to publish children’s books with offensive illustrations sends the wrong message to anyone who comes across them. It is crucial for all children to be exposed to truthful and positive images, not just non-white children; otherwise, we as Americans have no chance at becoming a better nation where all are seen, heard and treated equally.

I hold out little hope for any mutual understanding from those respondents who replied with hate and disdain to my posting.

But I was heartened to hear from people who said they reconsidered their impulse to roll their eyes at the Dr. Seuss news. While they frankly expressed fatigue at times with the reexamination of misguided and immoral thinking and actions from the past, they acknowledged that they had discovered some understanding of the power of representation with further consideration. Many offered that when they recognized the significance of negative and offensive illustrations and how they contribute to division and hate – which is on the rise – they realized this fatigue was nothing compared to what non-white individuals had and continue to experience.

I have always cringed when people talk about the “good old days.” While I have many fond memories of the past, I am quick to recognize that it was far from perfect. I acknowledge that women, people of color, and any group considered to be “other” had to be submissive in that past. And that there were unjust laws in place or the mores of the time that limited the freedom of many of our citizens. That history must be confronted and identified for what it was… wrong. Calling it out doesn’t cancel anything or take away from what was positive about those times, nor does it proclaim that everything nowadays is ideal and without reproach.

Fortunately, progress is being made and representation in books and other media is becoming more inclusive and more positive; that said, we need to be vigilant in looking honestly at the past, as well as critically at how people are represented going forward.