This piece was first posted on Substack. To comment, please go there.

In public health, we talk a fair bit about diversity. This conversation is consistent with the broader goals of our field. Our mission is to serve populations with many different backgrounds and perspectives. Engaging with a range of groups—with all of us as different people united in our shared humanity—means celebrating the diversity we reflect, and working to ensure this engagement is fully inclusive. I have written previously about diversity. At perhaps the most basic level, a commitment to diversity calls on us to ensure that the public health community is a welcoming space for people of many races, religions, nationalities, and expressions of gender/sexual identity. This strikes me as a necessary condition for our efforts, worth pursuing, always, as a key priority.

But diversity does not just mean diversity of identity. It also means diversity of opinion. A benefit to having communities of people with different backgrounds and identities is that each person has a unique perspective they can bring to bear on the conversations that happen in these spaces. These perspectives can sharpen our collective thinking, helping us to do what we do better. It is important to note that diversity of identity is often closely linked to diversity of opinion, but one does not invariably follow the other. The deciding factor is whether or not we value viewpoint diversity enough to encourage it the same way we encourage diversity of identity.

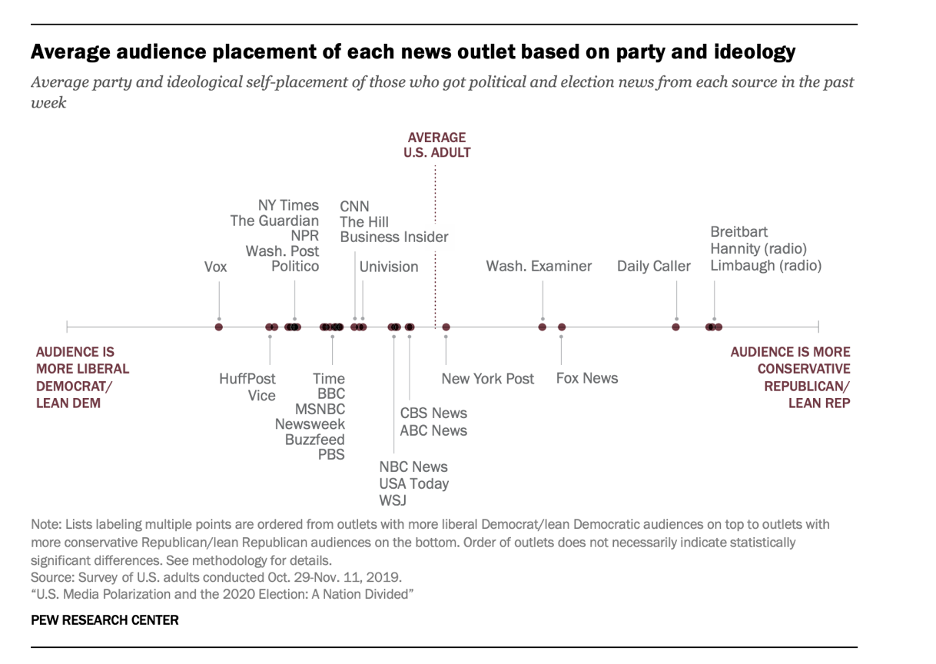

Many of us in public health would likely say that we believe in both kinds of diversity. We would say we understand that creating space for different views is core to generating high-quality thought that supports a healthier world. But belief is less about what we say, and more about what we do, and the fact is, it can be difficult to put into practice a belief in viewpoint diversity, which is why we do not always do it. Exposure to ideas with which we disagree can be uncomfortable, to say nothing of ideas we find abhorrent—and we will encounter both in a context of viewpoint diversity. It is far easier to say we value such a context, while doing little to welcome diverse views into our spaces, and raising no objection when attempts are made to actively exclude uncomfortable or heterodox ideas. This is perhaps understandable. Much about the past decade or so has reflected our tendency to prefer the company of the like-minded to people and ideas we identify with an out-group. This is seen, for example, in the polarization of news media audiences in the US (see figure below).

This speaks to a key point not just about promoting viewpoint diversity, but about the broader challenge of adhering to a vision for society and for public health which is rooted in the small-l liberalism and Enlightenment principles that do so much to support progress (see prior writing on this). This work, in fundamental ways, runs counter to the imperatives of human nature. It is not easy, or intuitive, to create space for the civil airing of different views. It is easier to simply embrace what is comfortable and familiar, and to avoid all else. It is not easy to actively seek out, and sustain engagement with, people who are not part of our in-group.

Why, then, should we bother to pursue this engagement? Why does a vision of diversity which includes viewpoint diversity matter? I would say that it matters because we aspire to a world where (with a few exceptions, discussed below), a plurality of perspectives can be aired, recognizing that the alternative—a world where ideas are suppressed—is much worse. It also matters because exposure to a diversity of perspectives helps us to sharpen our thinking about the issues that are core to health, and to see where we are potentially wrong. When we are exposed to viewpoints which challenge our own thinking or that of the consensus, such viewpoints can motivate us to ask ourselves how it is that we know what we know—do we hold an opinion simply because everyone says it is correct, or do we hold it because, if pushed, we are indeed able to make a solid, point-by-point case for it? In this way, even opinions we may regard as far outside the borders of good sense can serve a useful, even indispensable, purpose.

This argues for an approach to diversity which embraces viewpoint diversity along with diversity of identity, to inform a context which generates the best possible ideas. A practical example of viewpoint diversity at work, with ideas outside the mainstream sharpening our grasp of foundational arguments, was raised by the late journalist Christopher Hitchens, an often controversial thinker, who once asked an audience what they would do if they met someone who thinks the world is flat. The vast majority of people believe the earth to be round, yet how many of us can marshal the specific arguments in favor of this position? Encountering someone whose views are far outside the mainstream on the issue can help make sure we are able to make the correct case, by reminding us that it is never enough to believe something simply because everyone else does, even on an issue as basic as the shape of the earth. We should never hold a position we cannot justify under scrutiny. Our aim should be to persuade people of our views, rather than to simply say “Trust us, we are right.” This means we must be able to argue persuasively in favor of our positions, no matter how self-evidently correct they may seem. Our role is to unify, not divide, and this goal is best served by a persuasive approach rather than a moralistic, lecturing one.

This is particularly true during the present stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, when a key challenge of the moment is encouraging vaccine uptake. We know that vaccines are safe and effective—this is among the most widely understood and accepted facts in medicine and public health today. Because of this overwhelming consensus, it is understandable that many of us may not have at our disposal the specific arguments on why vaccines in general, and COVID vaccines in particular, are indeed reliable. Yet now is precisely the time when it is most necessary to be able to express, in a compelling and clear way, why our beliefs about vaccines are correct and beliefs to the contrary are wrong. While it can be frustrating to engage with those who disagree with us on vaccines, such engagement is core to sharpening our arguments so they might cut through the mistrust of the present moment and help change minds on this most important of issues.

Given the stakes of these conversations, it is clear that we should not merely tolerate views we may not share, or the presence of people with whom we may vehemently disagree, but that we should actively seek out encounters where we will face intellectual pushback. In a past column, I cited—to some criticism, I realize—the Polish revolutionary Rosa Luxemburg, who said, “Freedom is always and exclusively freedom for the one who thinks differently.” This suggests the importance of creating space for those who indeed “think differently.” This does not mean, of course, that we should entertain all views in the spaces we inhabit. While a free society—rooted in liberal, Enlightenment principles—benefits from a maximalist approach to free speech, it is reasonable to exercise some discretion about the speech with which we engage in the specific context of our work. For example, in my role as Dean of the Boston University School of Public Health, I have long thought about how to support a space which maintains viewpoint diversity while also maintaining a respectful, inclusive academic conversation. To my thinking, there are three circumstances in which speech might be limited to the extent of refusing a platform to certain viewpoints.

First, we need not give a platform to viewpoints which are not open to rebuttal by those who take the opposing position. Core to viewpoint diversity is the tried-and-true principle that the best way to deal with unsound views is not censorship, but more—and better—speech. Views must always be open to rebuttal, and we have no obligation to shield anyone’s opinion from public critique. But it is also true that forms of speech that cannot be rebutted—for example, name calling—should not be tolerated, because they do not represent productive perspectives but rather systematic efforts to tear down others who cannot defend themselves. We should have little space for that in the context of our work.

Second, our pursuit of viewpoint diversity should not extend to views which endorse or encourage violence. Violence is inimical to health and to the proper functioning of society, and should have no place in any community. Indeed, a key achievement of the Enlightenment was to create a culture where passionate argument could take the place of physical conflict. It is necessary, then, to embrace the liberal principles of free speech and viewpoint diversity to support a context where differences can be addressed without a resort to violence and where those who would promote violence will find no welcome.

Third, we have no obligation to provide a platform to those who traffic in well-established falsehoods. This is to say that, while it may be useful to engage in a conversation with a flat-earther, we do not need to invite her to speak at any events we may be hosting. Just because we embrace engagement with views we may not share and which may not be supported by the data does not mean we should amplify them. A key tenet of liberalism is balance, moderation, and this is particularly applicable to our thinking about which voices we choose to elevate and which we do not.

Guided by this framework, our pursuit of diversity should include the viewpoint diversity that can do so much to improve our thinking and help us more effectively support health. This includes engaging with viewpoints which may seem so wrongheaded as to be useless. Such viewpoints can serve as intellectual whetstones, helping sharpen ideas and shed new light on old thinking. Indeed, I almost titled this essay “What is so bad about bad ideas?” While I ultimately decided that this might not fully reflect what I wanted to discuss here, the question is, I think, worth asking. There is a current of thought in the present progressive discourse that there is something corrupting, even harmful, about contact with bad ideas. And, certainly, such ideas should be approached with care, contextualized, and, when necessary, vigorously rebutted. But the notion that the correct approach to bad ideas—or different ideas—is to just ignore them, at the expense of viewpoint diversity, does no favors to a culture of thought robust enough to support a healthier world.