Welcome to our special section, Thrive on Campus, devoted to covering the urgent issue of mental health among college and university students from all angles. If you are a college student, we invite you to apply to be an Editor-at-Large, or to simply contribute (please tag your pieces ThriveOnCampus). We welcome faculty, clinicians, and graduates to contribute as well. Read more here.

Over twenty years ago, like many college students in the throes of existential questions, I had half-knowingly embarked on a quest for meaning. For much of the time, I felt like a castaway in uncertain seas with only gut instinct and grit as my guide. In retrospect, I can see that if I would have had better tools and guides, my disorientation, and the angst that followed in its wake, could have been dramatically reduced.

As a high school humanities teacher at San Domenico School, my classes are designed to make these disciplines relevant to students’ lives. My aim is to help students discover how the humanities can offer insight into the most meaningful facets of our lives – relationships, education, work, money, and belief itself. This is precisely what attracted me to an integrative educational model called Purpose Learning: the promise of helping students develop goals that are meaningful to the self and consequential to the world.

The latest psychological research has revealed a crisis of meaning is growing in our younger generations. Dr. Bill Damon, Director of Stanford’s Center on Adolescence, has said that, “The biggest problem growing up today is not actually stress; it’s meaninglessness.” While high school students are the most stressed-out demographic in the U.S., it isn’t simply because they have too much to do but largely because they don’t know why they are doing it. Purpose Learning provides a necessary antidote to our system of education that champions carrots and sticks over meaning and purpose.

There is an educational organization developed at the Stanford University d.School focused on helping to reimagine education with Purpose Learning curriculum. Project Wayfinder draws upon purpose development research and brain science to aid our next generation to develop meaningful goals that positively impact our world.

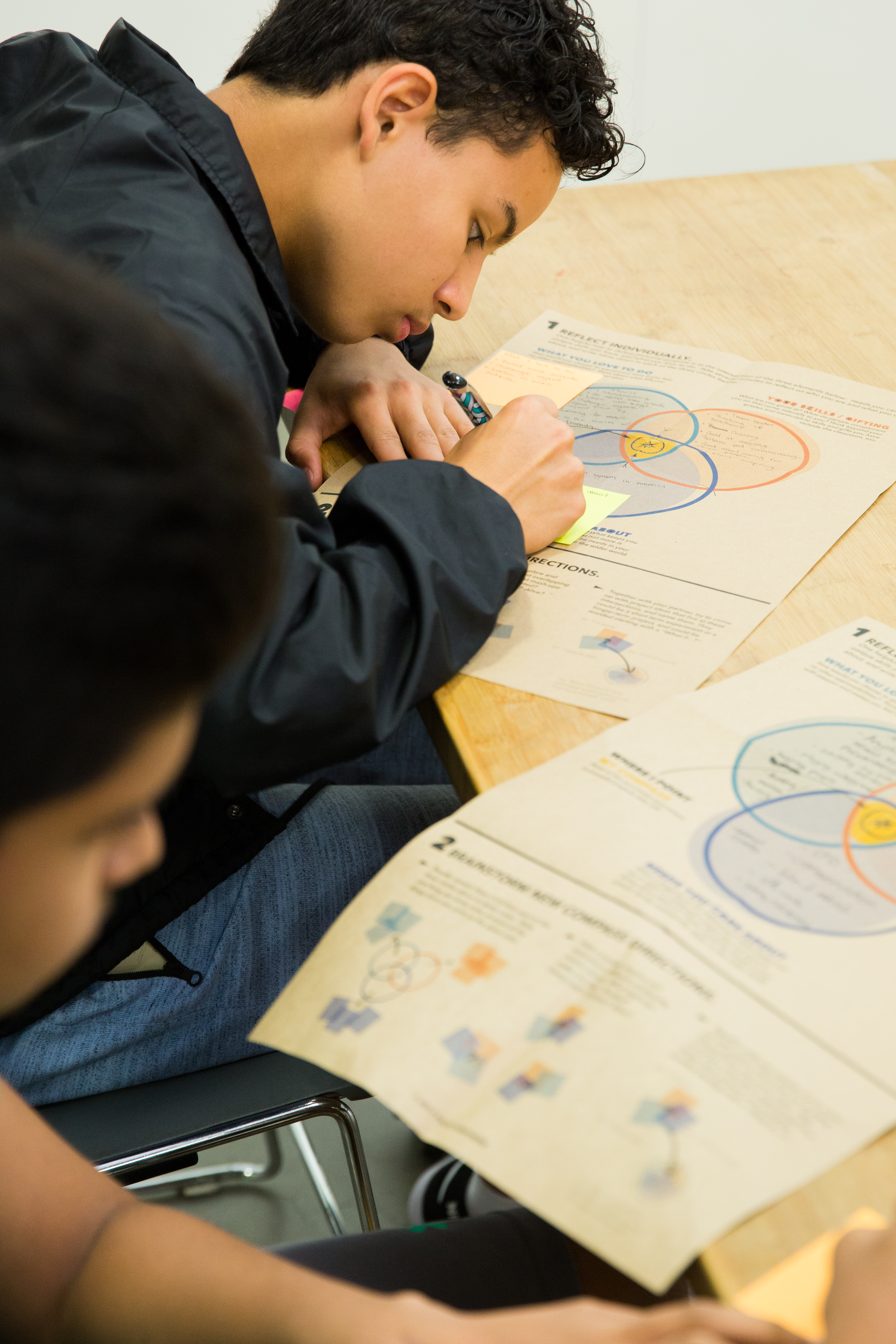

The lessons explore themes such as self-awareness, world awareness, and purposeful action. Underpinning each activity are “big life questions” such as: what do you value, what holds me back from new paths, how do I fit into the world? As students progress through the toolkit they begin to develop a purpose compass. The purpose compass enables students to distill their values, strengths, and concerns into a discernible orientation in life. Purpose isn’t singular and it can evolve throughout one’s life. This is why the metaphor of wayfinding is powerful. It helps shape our perceptions and actions so that we are more attuned and adaptable to life’s inevitable shifts and changes.

Wayfinding refers to the practices of people throughout history who have “read” the natural world to travel across immense areas of water and land. Knowledge of cloud formations, subtle changes of weather, the color of the sky or sea, absence or presence of flora and fauna, and the starry night sky, could reveal significant signs and patterns to help them find their way.

In a culture fixated on linear progress, randomness, disruptions, and uncertainty are to be avoided like the plague. Yet these features are baked into the fabric of life. The metaphor of wayfinding empowers us to become comfortable with, and even grow from, uncertainty. Traditional wayfinders, like the Polynesians, almost never travel on a linear path. Using the signs and patterns of nature, they are constantly calibrating along the way.

It didn’t take long for students to voice their opinions about Project Wayfinder. Into week two of the course, a unanimous sentiment emerged: this should be a required class. As we finished the course and completed the toolkit, one of the seniors had this to say about her Wayfinder experience, “This class gave me an opportunity to examine what actually matters to me and how I can make that relevant and purposeful in my life. No other class I’ve taken has provided me with that experience.” Another student captured their experience with this reflection, “Project Wayfinder allowed me to slow down and reflect on my own accomplishments, ambitions and intrinsic motivations. By writing everything down and analyzing my experiences and life values, I have found what it is to be present, to create meaningful goals and seek purpose in all that I set out to do.”

Project Wayfinder helps to map students and teachers alike back into a landscape of meaning and purpose. While purpose is a robust trait it doesn’t develop without the right conditions. In facilitating this curriculum I’ve experienced how psychological safety and vulnerability create the fertile ground for purpose to take root. And the teacher is the primary steward of this ecosystem. An atmosphere of compassion, respect, and support is vital for the exploration of purpose. Leading by example and with vulnerability creates a resonant tone. This includes doing the activities and sharing one’s own reflections and process around purpose. The journey of wayfinding is an ongoing process of growth, development, and self-discovery. It’s a countervailing force to our destination-oriented system of education. Though in the words of Ursula K. LeGuin, “It is good to have an end to journey toward, it is the journey that matters in the end.”

Subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

More on Mental Health on Campus:

What Campus Mental Health Centers Are Doing to Keep Up With Student Need

If You’re a Student Who’s Struggling With Mental Health, These 7 Tips Will Help

The Hidden Stress of RAs in the Student Mental Health Crisis