The devastating impacts of COVD-19 on human health are increasingly appreciated. The world is also waking up to the pandemic’s apparently positive effects on the planet’s atmosphere, ecosystems, and biodiversity. Ever since it was first detected in late 2019, the pandemic and resulting lockdowns have dramatically slowed globalization, especially the trade and travel that powered the largest economic boom in human history. Notwithstanding the incalculable pain and suffering caused by the virus, it has one silver lining. Specifically, efforts to contain the spread of the disease have temporarily reduced air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions—especially carbon dioxide (CO2), nitrogen dioxide (NO2), and particulate matter, or PM2.5. The most important question, however, is whether these reductions will be sustained after restrictions ease.

Within a few months of the spread of COVID-19 across Asia, Europe and the Americas, global CO2 emissions fell a remarkable 17 percent. The principle reason for this was the sudden drop in large-scale manufacturing, power generation, shipping, and transportation. NASA and Planet Labs detected unprecedented declines in road traffic, which in turn resulted in a stunning drop in NO2 above the world’s largest metropolises. As promising as these declines appear, most climate scientists are not at all optimistic that these short-term changes will persist in the long run. Their best estimate is that CO2 declines may end up at around 4 to 7 percent by the end of 2020. It is far too early to celebrate because the resumption of industrial activity and energy use could wipe out any gains in 2021.

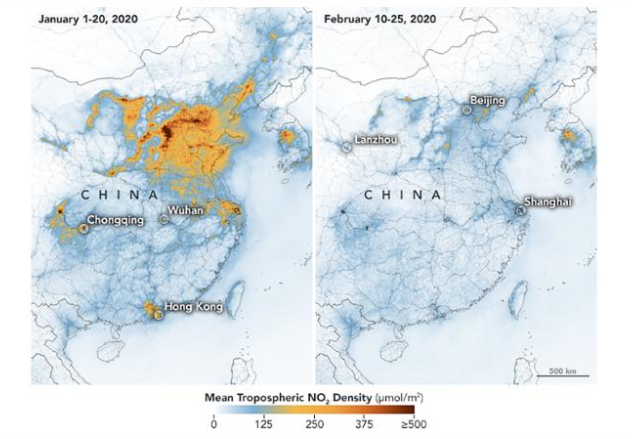

Clearer skies over China – Average NO2 levels (NASA 2020)

Few sectors were hit harder by COVID-19 than the airline industry. The outbreak is considered to be the worst crisis to have ever hit aviation, period. Around 70 percent of all flights were reportedly grounded by February 2020 and international travel declined by as much as 80 percent by the end of May 2020. The cost of air cargo tripled as shipping between countries ground to a halt. Not surprisingly, aviation’s carbon footprint shrunk by 60 percent by mid-2020. The sharp slowdown in aviation also disrupted the accuracy of weather forecasts, in part because the number of daily measurements of air temperature, humidity, and wind speed from airplanes declined from roughly 900,000 a day to only 300,000.

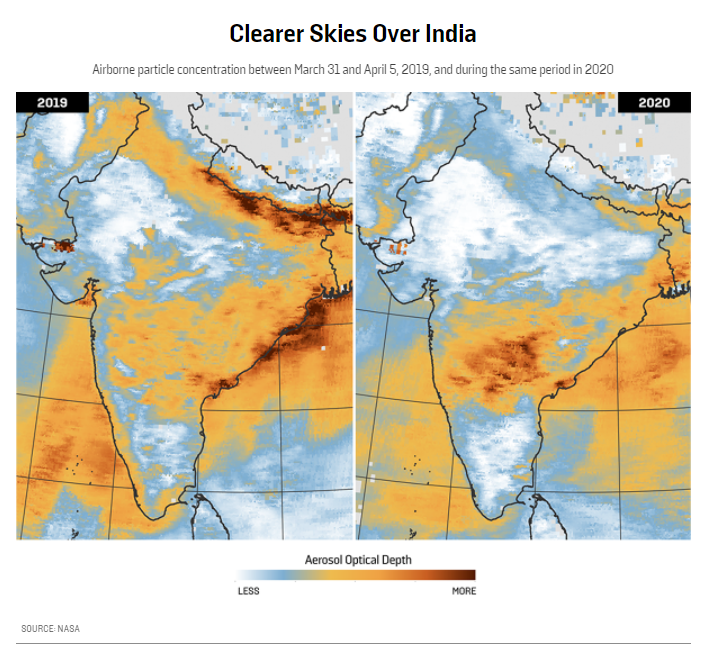

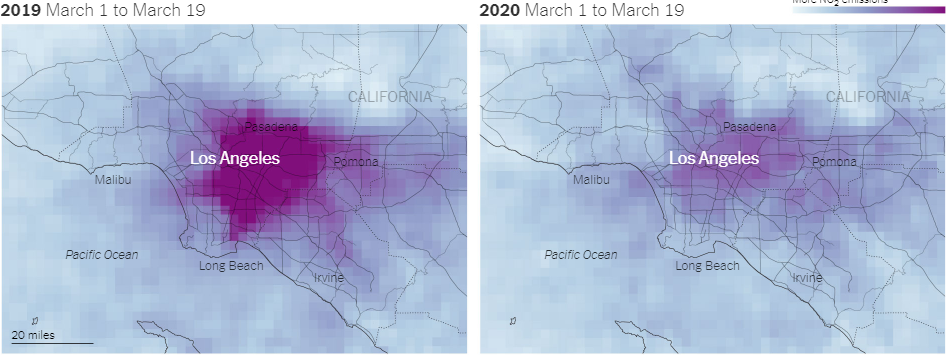

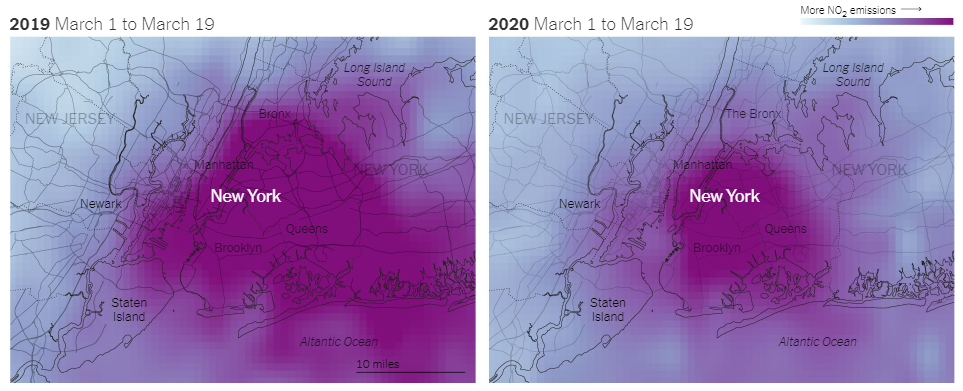

The pandemic also contributed to a sharp reduction in car, truck, and bus traffic when cities around the world went into lockdown. In a matter of weeks, weekdays became weekends and rush hours evaporated. In Europe, cities such as Milan, Paris, and London experienced declines in traffic of between 70 and 85 percent. In the United States, every metro area experienced a reduction in traffic of at least 50 percent, and the lowest amount of driving since the 1970s. Crowded Indian cities such as Bangalore, Delhi, and Mumbai saw traffic rapidly decline, which helps explain why levels of NO2 and particulates plunged by up to 60 percent. And in China, NO2 and CO2 emissions declined nationwide by 30 and 25 percent, respectively, after one-third of its cities went into lockdown. Wuhan experienced a stunning 63 percent drop in nitrogen dioxide emissions in the months after the city of 11 million people was shuttered.

Smog above India – Average PM2.5 levels in 2020 and 2019 (NASA 2020)

Instead of lasting declines in pollution, there is evidence that industrial pollution and air-travel emissions are creeping back up around the world. Car traffic is increasing in many cities once governments relaxed quarantine measures. Since many city dwellers are justifiably anxious about returning to public transit, the risk of a surge in commuting by car is real. The future of greenhouse gas emissions ultimately depends on what national, state, and municipal governments do next. Some mayors, city councils, and urban planners are busily trying to modify their urban spaces to favor pedestrians and greener modes of transportation. They are finding genuine support from local residents: In a recent international survey, three of four people in the countries polled expect their governments to make environmental protection a priority when planning the post-pandemic recovery.

More positively, COVID-19 is intensifying support in some parts of the world for more investment in emissions reduction and “building back better” than before. Before COVID-19, climate action had shot up the agenda, fueled in part by widespread protest movements such as Friday for Futures and the Extinction Rebellion. And while governments are confronting massive fiscal challenges and soaring deficits, there are many people who are reluctant to go back to the old normal. Some politicians recognize that COVID-19 has created a space to push forward plans for a greener economy. Enlightened city leaders recognize that greener cities are healthier cities. This helps explain the clamping down on cars and the rapid spread of bike and pedestrian lanes and ride-share initiatives from Athens, Barcelona, Berlin, Brussels, Paris, and Rome to New York, Minneapolis, Seattle, and San Francisco. The United Nations even established a World Bicycle Day to spread awareness about how bikes can help power post-COVID-19 recovery.

Smog-free cities – NO2 levels in 2020 and 2019 (NYT/Descartes Lab 2020)

But there are also risks that COVID-19 will delay action to address the world’s multiple climate crises. Among other things, it has slowed down international negotiations such as COP26, the annual pledging conference to keep global temperature rises below 2 degrees Celsius, and diplomatic progress on agreements designed to protect biological diversity and the oceans. The pandemic is likewise distracting people from ongoing environmental calamities including rampant forest fires and the industrial-scale deforestation of the Amazon in Brazil, as well as Colombia, Cambodia, Indonesia, Nepal and Madagascar. The economic distress generated by COVID-19 could also weaken national climate policies and investments, as countries resort to fossil fuels, cut green subsidies, and abandon renewable energy plans. There’s also a risk of an increase in pollution, including increased micro-plastics entering waterways due to the massive increase in disposable gloves, surgical masks and other non-recyclable products.

Although they helped generate climate dividends, lockdowns are not the solution for meaningfully tackling climate change. Strict quarantining measures have slowed emissions and this in turn should at least partially reduce mortality and morbidity associated with air pollution, which causes more than 4.2 million deaths every year (it could also increase risks for poor, migrant and refugee populations who forced indoors). But the crippling economic, social, and psychological effects of restrictive lock downs are hugely damaging for people’s livelihoods, especially in poorer and more vulnerable communities. The fundamental point is that humans have unlimited needs, but the planet has limited capacity to satisfy them. The most important question in the short-term is whether governments, businesses, and societies can make the right decisions to ensure a downward trajectory of emissions over the next decade.

Clearer waters in Venice – 2020 and 2019 (Planet Labs)

While a comforting idea, COVID-19 will not heal the earth. In the first half of 2020, photos of wild boars in Barcelona, goats taking over Welsh cities, clear views of the Himalayas from Delhi, and aquamarine canals in Venice circulated across the internet. Hopeful memes on social media suggested that COVID-19 was healing the planet, that nature’s tremendous capacity for regeneration had been activated, and that humans were the virus. And while it is true that air, noise, and water pollution as well as greenhouse gas emissions temporarily declined in the first half of the year, there is virtually no chance this will be sustained in the post-pandemic era if radical measures are not taken to decarbonize the global economy and alter consumption habits. The only way to truly heal the planet, and save ourselves, is to take this opportunity to build radically greener economies, invest in renewable energy, phase out fossil fuels, and permanently shift to green mobility solutions.

***

Robert Muggah is a principal at the SecDev Group, a co-founder of the Igarapé Institute, and the author of Terra Incognita: 100 Maps to Survive the Next 100 Years.