Where most philosophers concern themselves with “how to be good,” there’s one guy named Epicurus who concerns himself more with “how to be happy.” Later, he formed a philosophical school called Epicureanism.

Among many Epicurean concepts, there’s one called “tetrapharmakos,” also known as the “four-part cure.” As the name suggests, it’s a set of four principles that Epicurus recommends to live a happier life.

While these ideas are ancient, they are still relevant today. I’ve been practicing tetrapharmakos for a few years now, and I’d say it’s been tremendously helpful. You might want to try them yourself and see if they work for you.

Before we start, if you are completely unfamiliar with Epicureanism, you might want to read this introductory guide first.

Otherwise, let’s get right to it.

Tetrapharmakos

The etymology of “tetrapharmakos” is quite simple: “tetra” means “four” and “pharmakos” means “remedy” or “medicine.” They are both Greek words.

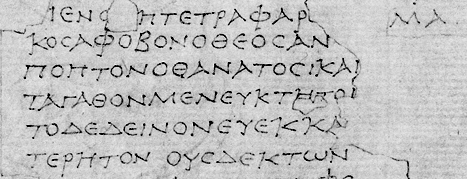

Originally, the term refers to a compound of four actual drugs: wax, tallow, pitch, and resin. Later, it’s used metaphorically by Philodemus, one of Epicurus’ disciples, to refer to the core principles of happiness in Epicureanism, since both of them function as a “cure” and are four in number.

Philodemus put together the tetrapharmakos from fragments of his master’s teachings, and summarized it into four points:

- Don’t fear God.

- Don’t worry about death.

- What is good is easy to get.

- What is terrible is easy to endure.

Sounds simple enough? Let’s examine each one closer.

Don’t fear God

While some people regard Epicurus as an atheist, he doesn’t necessarily advocate atheism. He merely points out that our fear of God is can be a huge factor in our unhappiness. Think about it: Some religious people are overly afraid of receiving divine punishment that they can’t live their life to the fullest. They overthink their morality so much it paralyzes them.

Well, if we fear God, it’s likely because we view Him less as a benevolent creator, and more as a spiteful being hell-bent on punishing our misdeeds.

As Epicurus wrote in Fragments:

“If God listened to the prayers of men, all men would quickly have perished: for they are forever praying for evil against one another.”

While this stern conception of God is still present in modern religions, Epicurus’ observation is originally directed towards the gods of the Greek pantheon: Zeus, Poseidon, Hades, Ares, Athena, and so on.

He argues, why would an all-powerful being concern themselves with the activities of puny mortals? Also, destructive emotions like anger and partiality are human traits that imply weakness and imperfection — why would a divine being possess those traits?

Of course, every religion has its nuances, and Epicurus’ thoughts might not resonate with everyone, so take these words with a grain of salt.

However, there are perhaps some lessons we can all try to understand:

If you’re religious,

Don’t get overly fixated on God’s anger and divine punishment, focus on His mercifulness instead. By all means, embody what is good and avoid what is evil — but not because you’re afraid. Do it because it’s the right thing to do.

If you’re an atheist,

Even if you don’t believe in a supernatural deity, this increasingly secularized world still houses authority figures that have a certain degree of control over your life: The government? The media? There are still a lot of “gods” you should be wary of. As an atheist, who do you fear?

According to Epicurus, once you learn to not fear God, an enormous burden will be lifted from your shoulders — and it’s incredibly relieving.

Don’t worry about death

This second cure is a huge one. Why? Because death is the mother of all anxieties: pain, aging, hunger, illness, abandonment — if we trace our fears to the source, we will arrive at one thing, and one thing only: Our mortality.

We all have our traumas and phobias, and surely you understand how these afflictions can be debilitating. But they are actually defense mechanisms that our minds develop to protect ourselves from danger, therefore reducing the risk of death. For better or worse, these anxieties prolong our lives.

In both length and intensity, death is the greatest anxiety of all, Epicurus said. It pains us more, not with its actual presence, but with our expectation of it.

He wrote in Letter of Menoeceus:

“Death, therefore, the most awful of evils, is nothing to us, seeing that, when we are, death is not come, and, when death is come, we are not. It is nothing, then, either to the living or to the dead, for with the living it is not and the dead exist no longer.”

Epicurus argues it’s useless to worry about death. Unless you believe in the afterlife or reincarnation, death is simply a return to oblivion. What awaits after death is the same condition we’ve been in before we were born.

When it’s absent, we exist. When it arrives, we cease to exist.

Thus, if you can erase your worries about death, you will free yourself from a whole lot of other worries. It’s cathartic.

What is good is easy to get

Epicurus wrote in Principal Doctrines:

“The wealth required by nature is limited and is easy to procure; but the wealth required by vain ideals extends to infinity.”

Humans don’t need much to survive. Basic needs like sustenance (food, water) and shelter (a roof to sleep under) are relatively easy to obtain.

Things only get complicated when we move beyond the basics, for excessive luxuries serve little more than to feed our greed and gluttony. Moreover, the process of fulfilling these vain desires often puts us through needless anxiety. In the end, they won’t add that much value to our lives, so why bother?

Epicurus himself was believed to only possess a wardrobe of two cloaks, and a daily diet of merely bread and olives — sometimes with a side of cheese.

Granted, “what is good is easy to get” might be an over-generalization. As you surely know, there are poorer parts of the world where basic necessities like decent food and clean water are difficult to obtain, but they are outliers, not the norm. The majority of the world is now living in abundance.

If anything, this gives us another reason to not seek pleasure beyond our basic needs: So we can give them to those who need them more.

What is terrible is easy to endure

This last point is perhaps the most controversial among the four cures. Some people might even say that it’s stupid. After all, many of us may have seen those who are closest to us (or even ourselves) undergo terrible suffering, and we know for a fact that it’s anything but easy.

Well, the life of Epicurus himself isn’t free from suffering. In fact, it was quite ironic that, as a philosopher who spent his life exploring how to be happy, he died from a painful disease (some people believed it was kidney stones).

Despite having to endure such agony, Epicurus wrote in Letter to Idomeneus that, on the last day of his life, he was happy.

At another time, he wrote in Fragments:

“Let us not blame the flesh as the cause of great evils, nor blame circumstances for our distresses.”

Perhaps, if the previous cure teaches us to lower our threshold of pleasure, the lesson in this one is to increase our threshold of pain. We are more resilient than we think we are, and we can endure more than we think we can.

To put things into perspective, medical science has come so far today that most diseases that are lethal during Epicurus’ lifetime can now be treated with ease. If anything, this just made “what is terrible is easy to endure” even more relevant. We now have more means to diminish our suffering, and that’s huge. It’s a gamechanger.

If something terrible happens, ask yourself: “Is this something I can endure?”

It’s surprising to realize how often the answer is actually “Yes.”

Final thoughts

There you have it. An ancient four-part cure to help make your life happier, as prescribed by Epicurus the philosopher. Hopefully, at least one of them works for you (if not all four). I wish you the best of luck.