“Oh, if we only knew what we do

when we hack and rack the growing green…”

Gerard Manley Hopkins, (from Binsey Poplars, 1879)

It was 1978, and my wife and I had recently moved to a remote cottage on the side of a hill (called “Tyn-y-fron” in the Welsh language) in North Wales. I had recently given her a spaniel puppy, but one warm spring evening we were distressed to find that it had strayed and was nowhere to be found. We reckoned that most likely it had followed a group of hikers along a nearby trail leading up to a large tract of heather moorland. It was getting dark, so we resolved to set off before dawn the next day to follow the trail.

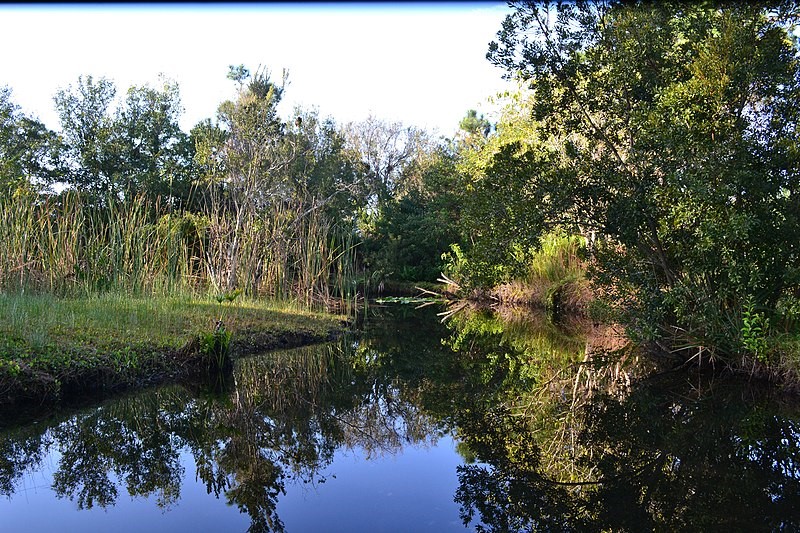

After a few miles we happened upon a fold in the moor concealing a small lake surrounded by low trees and a tangle of shrubs. The few open spaces were filled by waving grasses and speckled with brightly coloured wildflowers. By now the sun was creeping over the horizon and dozens of small birds were treating us to a cacophonous dawn chorus. The air hummed with insects. Dragonflies darted among the reeds. Frogs croaked from the muddy banks. Ripples from rising trout spread across the water’s surface. It was a little corner of wild, untouched paradise – a hidden gem, and it captivated us. We might have stayed all morning had our mission not been so urgent, so reluctantly we pressed on.

A mile or so later we came across another tract of woodland, but a starker contrast could hardly be imagined, with its closely packed, regimented ranks of conifers. We stepped tentatively into its gloomy interior, the snapping of dead branches under our feet shattering a tomb-like quiet. It was a barren, almost sinister landscape, devoid of all visible life. Our calls echoed through the silence. An ancient oak woodland had once stood here, we later learned, but it had been completely destroyed for its timber. A rich diversity of species born of thousands of years of evolution had been replaced with this bleak monoculture. It was a classic instance of the methodical, wanton destruction of the natural world repeating itself all over Europe, and indeed the world, and I had foolishly thought to escape it by retreating to the wilds.

It had been ten years since bulldozers had begun to rip though the wild-flower rich meadows of my home village in a picturesque corner of rural England. Here, ironically, a poster of the church and cottages had earlier been used to project the image of an idyllic, unspoilt England to American tourists. Now machines crushed the wild-flowers into the mud, tearing deep gashes in the earth into which concrete, steel and brick was implanted. That was just the beginning: by 1976 the stream, where as children my brother and I had played, caught minnows and sticklebacks, spied water voles and kingfishers, had dried to an evil yellow trickle emanating from a factory wastepipe. Not long later the remaining water-meadows, with their damselfly-haunted dew-ponds, legions of croaking frogs, throngs of iridescent beetles, multitudes of brightly coloured butterflies, its bull-rushes, meadowsweet, primroses and cowslips, were utterly destroyed – buried under six feet of landfill – discarded soil and building rubble – in a frenzy of ignorant money-making. Those responsible had no awareness or care of the true cost of their actions: to them it was just “progress” – the catch-all word that justified just about anything in that era.

Next, lines of vast electricity pylons came marching close by the village, blighting the views across the rolling farmland. The coup-de-gras was a 6-lane highway, carving a deep wide groove through the site of an important Roman settlement. At peace until then for fifteen hundred years other than the soft tread of plough-horses and later the occasional low thrum of tractors, now the constant moan of traffic intruded rudely. For me, every bird silenced, flower meadow lost, copse felled, peacefulness shattered, was a profound sadness. This was also the era of DDT, of anthrax, of the Cold War. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was one of only a very few voices warning of what was happening and was to come – extinctions on an unimaginable scale, yes, but also the loss of something equally precious in our lives – tranquillity. To compound all this, from abroad came news of the accelerating devastation of great tracts of south American and Indonesian rainforest with their precious cargos of wildlife, and of the insidious pollution and rampant pillaging of the oceans. All I could see was a one-way street to oblivion – to the destruction of our beautiful planet and its natural wonders that I passionately believe we have a duty to preserve for generations to come.

The Wales incident was thus the last straw. I realised then that there was no running away any more – the destruction was everywhere. But ten years on something profound changed in me: my anger and despair gave give way to a quiet determination to understand the reasons for our destructive behaviour – not superficial ones like money and greed, but the deep impulses that drive all living things. Science was plainly the only possible route. We are, after all, merely creatures of Nature like any other. We share the vast majority of our genes with great apes, our closest relatives. So could genes and their corollary, evolution, provide the answer to why we humans degrade and destroy our planet in the full knowledge of what we do, I wondered? And if so, could it provide us with the means to control our excesses before it’s too late?

So it was that I came to spend some 20 years exploring why homo sapiens knowingly degrades the thing he relies on for his very survival – Nature – and writing about it. It was a fascinating and absorbing journey. It began, as it had to, with the writings of the father of modern evolutionary theory: Charles Darwin, progressing from evolution to anthropology to the brave new world of 21st century economics. Despite occasional setbacks along the way I never once regretted or gave up on this journey, a perseverance that was eventually rewarded with the very answers I had set out to find.

“Junglenomics” represents the culmination of all those years of study and thought, and I passionately believe it holds the remedies the world so desperately needs. However, its publication last year didn’t mark the end of my journey – far from it. It merely presented me with yet another mountain to climb – the biggest of all. That mountain is to bring it to the attention of those that have the power to influence policy. Challenging though this is, the memory of those devastated meadows, moors and woodlands, and the stark reality of climate change and species extinction worldwide, means that this journey and this mission will probably never end.

During Lockdown I was sent the following passage by a well-wisher. It never fails to give me renewed energy and determination when I need it. I hope it may inspire you too:

“Never stop believing in you; don’t allow the doubts in your mind to control you. Your road has been long, it has been full of challenges, but you took all the blows and you are still standing. Don’t stop now! Keep pushing, keep growing and most importantly never ever give up on your dreams because you are capable of more than you ever imagine. Believe in the impossible.”

www.junglenomics.com