“You won’t be able to recognize the things you really care about until you have released your grip on all the things that you’ve been taught to care about.” — William Deresiewicz

At far too young an age, American children will become painfully aware of a strange new desire to “fit in.” In those first few days of school, kids will scramble to form allies in a world without the watchful loving eyes of Mom or Dad. Friends become the universe; confidants of secrets, companions to endure boring classes, or just grateful pals to share a dry and slightly smushed PB&J sandwich, friend making is essential. And what better way to make friends than by fitting in with the other kids?

But something interesting happens over time. As children mature into young adults, they’re increasingly praised less for their similarity to their peers, and rewarded more for their uniqueness and differentiating abilities.

As high schoolers begin submitting college applications, they’re introduced again to another painful reality; no admission officer cares if they’re cool or popular. Instead, the notoriously unimpressible collegiate gatekeepers want to know exactly how students are different. Do they play sports? Do they outperform on standardized tests? Do they dominate class rank? In other words, what makes them special?

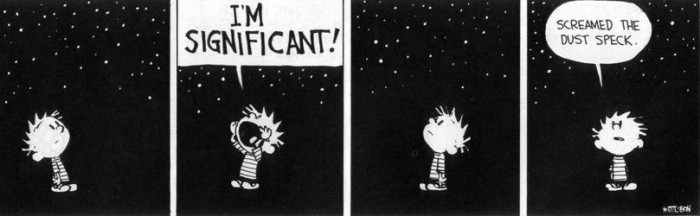

Thus, an internal conflict is born. On one hand, social instincts have been whispering into our ears from an early age that to make friends and be accepted, we should follow what everyone else does and chase what everyone else wants; but suddenly, we’re encouraged to differentiate ourselves amongst our friends and to declare our unique value propositions to the world.

When Corporate America management conducts annual performance reviews, they don’t sit there and say, “This year, let’s promote the five sales people with numbers closest to the average.” They promote the top five. Or, to further bolden this idea of value in originality, consider these artists in China who hand-paint thousands of Vincent van Gogh’s paintings to near identical precision. They sell them for $60. Meanwhile, a single van Gogh original costs $66M.

Whether we’re trying our hardest to fit in, or doing everything we can to stand out, I think deep down what we’re actually striving for is acceptance. Loving and accepting someone for who they are, regardless of differences is one of the greatest gestures humans can show each other. The irony of the situation is that often the people who crave homogeneity and fear differentiation are the same people seeking and accumulating status symbols as a way to signify their specialness and superiority over others.

I think the point I’m really trying to make here is that these conflicting desires to fit in and stand out, have lasting psychological bouts throughout our lives. We learn from experience when to strategically apply them as we edge our way closer, yet never quite arrive at the feeling of deserving acceptance. And that is because true and pure acceptance is intrinsic. No person, award, or institution can bestow this feeling upon you, it must come from you. And to begin this journey of unconditional love for one another, we start with ourselves.

Cartoon credit: Calvin and Hobbes by Bill Watterson

Originally published at brianhertzog.com.