There’s a crisis in male friendships, in case you didn’t know. Male loneliness starts in boyhood, and it’s harder for us to make friends than it is for women. Some are even saying our definition of masculinity is broken. I must not be a good example of what a modern man is supposed to be in our current culture, though. I’m a poet and a novelist, so expressing myself comes more naturally for me than for most men, I think.

Back in 2010, when my friend John Robinette’s wife Amy Polk was killed in a pedestrian traffic accident on the streets of Washington, D.C., I wasn’t sure at all how to “be” with him. I was at a loss for what to do, besides tell him how sorry I was for his loss.

At that time, John and I had been friends for about eight years, having met on the job at Johns Hopkins University. We bonded quickly over lunchtime conversations on politics, philosophy, religion, and current events. Everything you’re not supposed to talk about. But for us, nothing seemed off limits. And our friendship thrived on our openness.

The funny thing was, by outward appearances, you wouldn’t think we would get along at all. John is a progressive Democrat; I’ve been a registered Independent all my life. John is a Unitarian Universalist (I had to look that up when he first told me); I’m a Christian. John is outgoing and gregarious, your typical first-born. I’m an average middle child; the peacemaker. The labels of our differences are varied and many, but I think it was just these great differences that attracted us to each other, to test our worldviews, and to test ourselves and what we believed to be true.

Seeing John that first week after Amy’s death was excruciating for me. I pushed myself to be with him during his time of mourning. I didn’t know what to do—what anyone could do—to help him in his miserable situation. Then the thought came to me: just be with John; talk with him—like you always do. And listen to him, in deep conversation.

If I didn’t already have a solid friendship with John, I don’t think I would have proposed to him my unusual idea: to interview him over the course of the first year after Amy’s death. My hope was to meet John directly in his experience of sorrow, explore his grief with him, and discover what lessons might be learned.

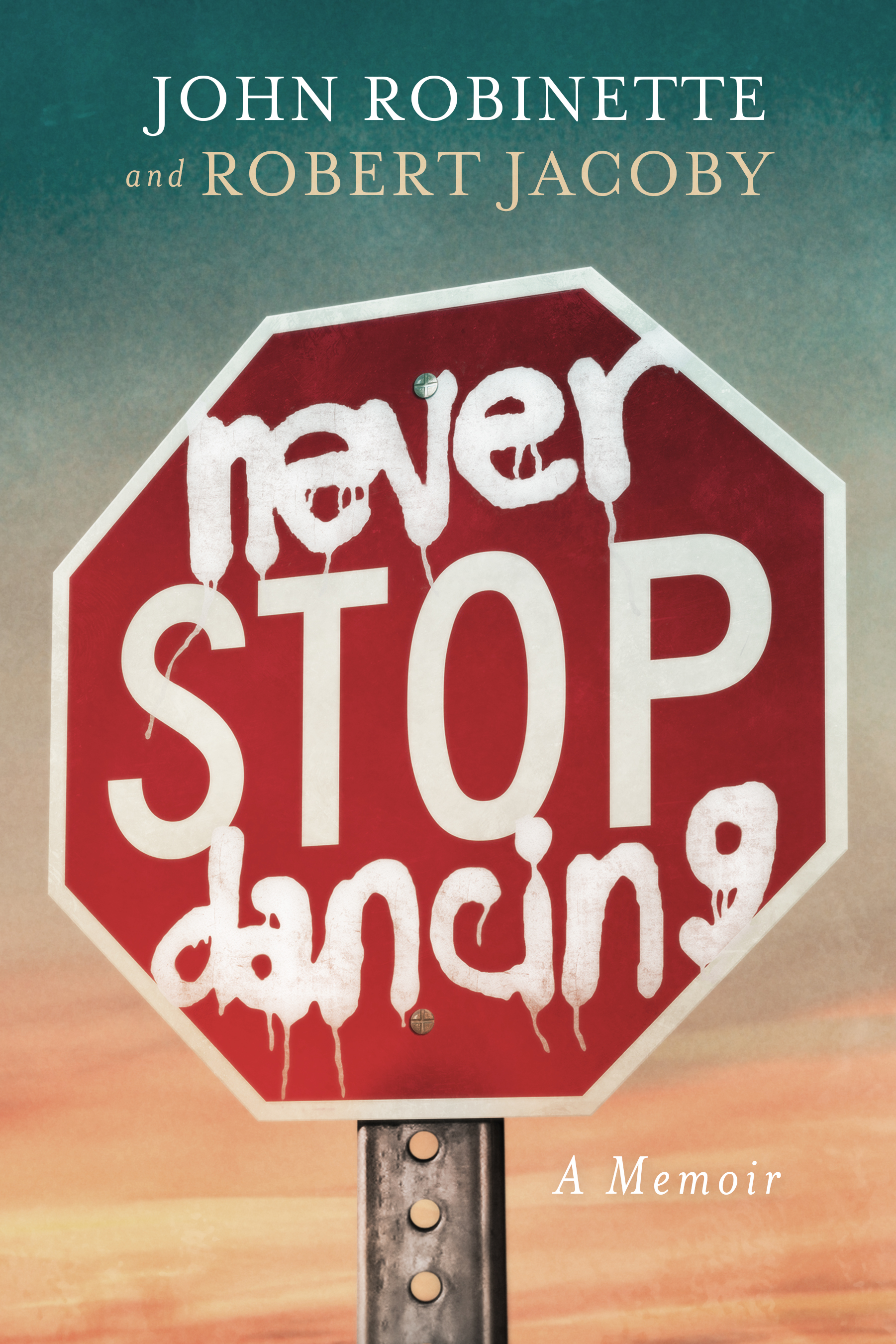

Now, nine years later, a book is born of our candid conversations and experiences. Never Stop Dancing: A Memoir examines how we look at life differently in the aftermath of a terrible tragedy, and at the same time how we understand the concepts of love, God, and religion in our lives. Our memoir-in-conversation also reveals a unique and enduring male friendship, and provides hard-won reassurance that one can and does go on after loss.

Some of the things I learned during that year of talking with John may help you be a better friend:

- Be genuine. Be who you are. Friendship is no time for masks, especially in grief.

- Give each other permission to be open and honest. A friend accepts the other person for who he is.

- Conversations can be medicine, and human “touch” can happen through words. It’s why we read books. To touch another life. To find ways to help us live a better life.

What John lived through may be common to humanity, but the experience he and I shared during that year is unique, perhaps, especially for men.

Based on excerpts from Never Stop Dancing: A Memoir by John Robinette and Robert Jacoby. A story of grief, male friendship, and healing conversations.