It was a bit of a shock.

After 12 years of increasingly high-profile leadership positions, Jay felt confident he was the best candidate for the CEO chair. He had survived steep financial downturns and pivoted his divisions so they could ride out their shrinking market share to a savvier and more sustainable model.

He was a survivor, but he was not going to be CEO.

Jay’s story’s is one we often see played out. A resilient leader who bounces back after each fall, only to hit a promotional wall. Why is that?

Looking at his 360 feedback, Jay recognized a troubling pattern. Although he had frequently saved the day and bounced back, he had done it at the expense of his team’s and partners’ trust and good will. He never really thought about what that really meant and the negative impact he was creating. His survival was dependent on draconian measures that hurt others in the name of short-term gain. Jay was not seen as an effective leader who could engage his people and shepherd the organization into the 21st century. Rather, his reputation was that of a volatile and punishing executive who only cared about his survival, his success.

Jay is an example how we, as leaders, may blur the lines between resilience and effective leadership. Many of us have seen and experienced how resilience is critical when we are in a triage situation – where the need is to survive and at least get to the next moment. It is relevant when we are in a transition phase – when we are learning from a setback and figuring out what’s next. Resilience is also a tool for the future, one that helps us transform using adversity as a springboard to create something new. In short, resilience allows us to recover – independently of how effective or strong our leadership is. Jay bounced back, consistent with the leader that he was, not the leader that was needed.

Rather than equating resilience with effective leadership, we can see it for what it is. A capability (set of skills) that builds agility and allows us the choice to up our game, challenge our growth and create a wider impact. If we are to embody resilience and increase our leadership effectiveness, we first need to build our capacity and capability for self-leadership.

How do we actually do this? How can we embody resilience and increase our leadership effectiveness through self-leadership? Is that even possible?

First, we can pause and take a breath. We inhale and as we exhale, we can consider and embrace a new definition of success. In this definition, success might mean making and acting on purposeful choices. It means taking care of ourselves, our teams and our organization while we pursue critical business results. It means proactively building strong and meaningful relationships that will help us weather the onslaught of change and crises that we almost certainly will face in the future.

Centuries ago, the old Painting Masters explored perspective, light and relationship to bring the subject of their paintings to life. So, too, we can explore three different orientations and what becomes meaningful with each. Specifically, we can look inward, outward and forward to better understand what is possible as a resilient leader.

Looking Inward

Unfortunately, there is no app for resilience; we must develop it. This process starts with self-awareness. Understanding and re-defining how we see leadership and resilience, as well as reflecting on the quality and effectiveness of our resilience, will help us best invest our energies and efforts. Here are some reflective questions you need to ask yourself to be that effective leader:

- How does my resilience show up? How do these behaviors/actions help me not only bounce back, but also be effective and conserve or grow my reserves for the next crisis?

Here we have to be brutally honest with ourselves and recognize when our resilience practices could be limiting our choices and ability to grow. We can take the opportunity to honestly assess ourselves. Are we being reactive to our triggers, our demons and fears? Or are we making thoughtful choices that build our reserves and allow us to be effective?

- Are the ways I show up as resilient consistent with my “best self”? Is the resilient leader I am now the same person as the resilient leader I aspire to be?

Gary Burnison, Korn Ferry CEO, wrote about his daughter, lamenting how so many people asked her, as a high school student, “WHAT do you want to be?” instead of “WHO do you want to be?” Creating clarity on who we want to be, regardless of title, as we lead others, as we influence and navigate a chaotic world can help us align our resilience practices to buttress our best selves.

- Where am I in my learning journey?

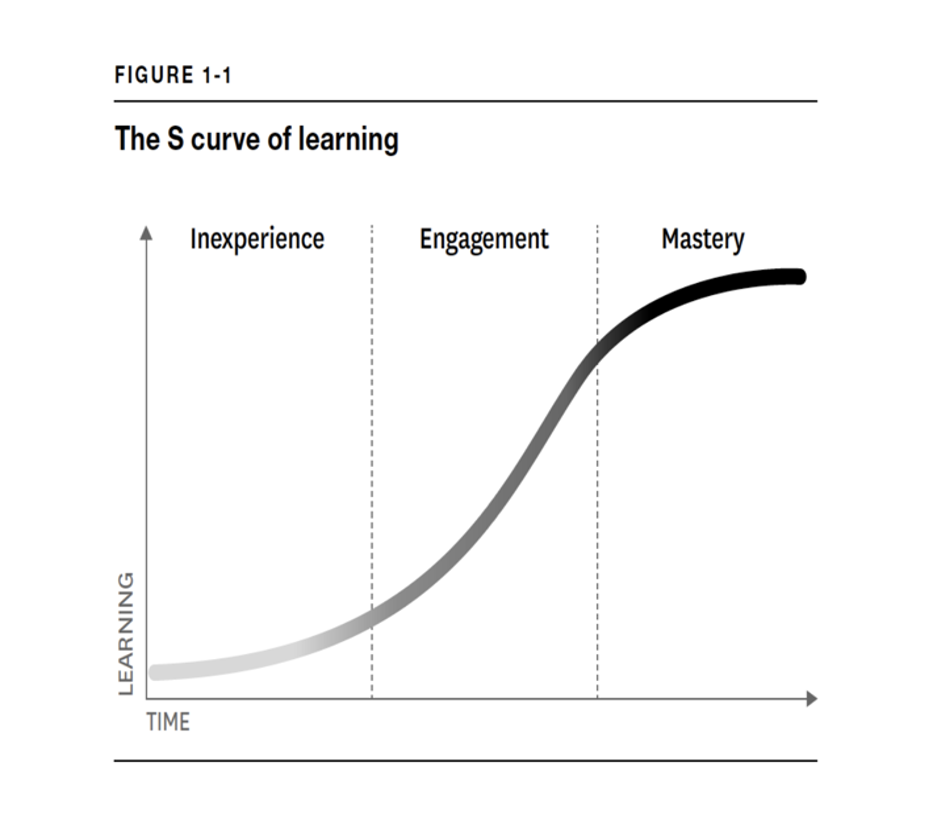

Wandering into the contractor’s section of a home improvement store can be daunting or fun, depending on your perspective. Knowing when and how to use a tool is critical for being effective, yet acquiring this knowledge is a process. Whitney Johnson has illustrated the learning journey in any particular domain as an S-curve[1]. It may be that we have mastered resilience in one context, yet in a different context we are inexperienced and find ourselves, again, at the bottom of the curve. Acknowledging where we are on our learning journey can help us determine what we may need to let go of and what we may need to embrace, consistent with the tenets of intentional change theory[2]. Are the successful practices of yesterday harmful today? What is an opportunity to grow now, today? As the masterful coach Marshall Goldsmith observed[3], “What got you here won’t get you there.”

- How am I showing compassion, forgiveness and accountability?

Too often we may feel shame and guilt for not being “resilient” enough or allowing those triggers and our behavioral tendencies to hurt us and others. It is precisely at those moments when it is crucial that we pause and interrupt the ingrained pattern. In that pause, can we can be compassionate and forgiving to ourselves? If a good friend was in the same situation, would we shame them? Would we make them feel “less than”? Hopefully not, so why do that to ourselves?

Yet, activating self-compassion and forgiveness does not mean we give up our accountability. In fact, the opposite is true. We are more likely to be able to restore our equilibrium, our center where we can exercise choice. Recognizing we have derailed, we can own it, call it out, apologize for it and even explore how to repair the damage done to trust and relationships. Our more effective choices offer a proactive and mindful stance essential to building our resilience and self-leadership.

Looking Outward

- What is my impact?

As we learn how to best embody resilience, we are giving shape and life to our best self. That will have a positive impact for you, your team and organization. The question is this: Do our resilience practices create a positive impact for others? Are we modeling and fostering engagement, collaboration, teamwork and courage? What works, not just for us, but for those we intend to lead and inspire? Analyzing our impact requires curiosity, openness, flexibility and humility in asking for and receiving feedback. How will others step up to contribute and help us on our journey? It requires courage to then apply what we have learned and willingness to keep the feedback loop open, healthy and ever expanding.

- Is it time for a new narrative and new practices?

As leaders and as humans we seek and create order and structure to help us make sense of the world. David Epstein writes in Range:

Chris Argyris, who helped create the Yale School of Management, studied high-powered consultants from top business schools for fifteen years, and saw that they did really well on business school problems that were well defined and quickly assessed. They employed single loop learning[4], the kind that favors the first familiar solution. Whenever those solutions went wrong, the consultants usually got defensive.

Epstein notes how Argyris found this particularly surprising as the consultants were charged with teaching others how to do things differently, yet they bristled when their usual solutions had to be abandoned for something different.[5] Sound familiar? Creating a narrative, a structure, a “hack”, helps us execute and deliver. However, we can be mindful that this does not become a “learned inflexibility”[6]. We want to capture the opportunity to author a new story that better serves our current individual and collective needs. The story need not abandon past lessons. In fact, it can be an opportunity to curate different factors and weave them into a more effective, nuanced approach to manage present and future demands.

- What wolf am I feeding?

In Cherokee folklore, there is a story of two wolves that represent opposing forces within each of us. The story teaches us that our future, our destiny is in our control. Our choices about what we nurture and feed shape the quality of the future we create and experience.

With the best intentions, organizations sometimes set up systems that cannibalize resilience and effectiveness. One organization wanted to encourage creativity to battle a new wave of competition in the marketplace. Their solution was to pit teams against each other in creative endeavors. In this zero-sum game, if our team won, yours lost. Compensation and promotion opportunities were dependent on your winning streak. One leader defined resilience as hoarding information, blocking other teams and ensuring his division made the best products. He was winning and, in his eyes, he was being resilient in the face of adversity. His counterpart saw this new system as hurting the culture of collaboration her team had so painstakingly created. For her, playing in the new system was creating burnout, not resiliency. As she explained to her SVP, “If I feed that wolf, he is going to destroy us.” This leader influenced, cajoled and sought to transform the wolf the organization had created into a workable system and ecology that not only was effective but fostered true resilience. What this meant for her was first looking inward and then aligning her values with what the system was asking of her. In seeing the dissonance, she had a choice to make – she chose to starve the wolf. When we look around and we see the wolf – the situations, the processes, the systems that hurt our and others’ resilience – will we be able to recognize it for what it is[7]? And if so, will we feed it?

Looking Forward

- How can I recognize when I need to upgrade my resilience practices?

Anxiety, worry and fear can create stress, triggering resilience practices that may no longer be sufficiently effective. An ever more pervasive VUCA environment and other disruptions may produce similar effects. What are we to do? A creative response can be to pay attention to our resilience fuel tank. When we are feeling empty, we can be alerted that it is time to sharpen or even re-design our resilience capability. Reivich and Shatté[8], in their research on resilience, found that there were seven different, learnable skills that upgraded one’s inner game and enhanced resilience. It included such skills as shifting limiting beliefs, reframing our interpretation, and taking different perspectives. Our mindful practice of these skills regenerates the dynamic nature of resilience, increases our engagement and accelerates our growth. - What do I need to model, coach and foster in others – both individuals and teams – to help them embody resilience?

I say “tomato” you say “tohmatoh.” Realizing that our resilience practices may not be universally adopted could be perplexing. However, in humility and in service to others and a shared purpose, we can reserve judgment and help those we lead explore how to develop their resilience. It might mean modeling, meta commenting[9] on and teaching various techniques they can choose from. It definitely will mean sharing objective feedback compassionately and constructively. And it ideally will mean coaching them to develop the ability to observe and reflect, look inward, outward and forward. This is about letting go of trying to mold (read as control) others to our way of thinking and behaving. Rather, it will involve helping them design and experiment as they create their own set of resilience skills.

To grow and become our best selves, we must practice self-leadership to elevate our game. This means upgrading how we think, feel, observe and understand the world around us, even creating new stories that will help us explain what it all means. No easy task, requiring adaptive responses to challenging times. All of this is predicated on awareness and choice. We have a choice of how we build our resilience and we have a choice, after bouncing back, to further our development as effective leaders. Resilience does not equal great leadership, but it does give us the choice to become great leaders. So, what will we choose?

[1] Johnson, W. (2019). Disrupt Yourself: Master Relentless Change and Speed Up Your Learning Curve. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press. The S-curve metaphor applied to learning was first developed by Charles Handy in his 1994 book, The Empty Raincoat: Making Sense of the Future. London, UK: Hutchinson. Subsequently, McKinsey & Company has extensively used the metaphor in its work. For a recent article, see Brassey, J., Kuo, G., Murphy, L., & van Dam, N. (2019, February 15). Shaping individual development along the S-curve. McKinsey & Company. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/organization/our-insights/shaping-individual-development-along-the-s-curve , June 12, 2020.

[2] Boyatzis, R., Smith, M., & Van Osten, E. (2019). Helping People Change: Coaching with Resilience for Lifelong Learning and Growth. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press.

[3] Goldsmith, M. (2007). What Got You Here Won’t Get You There. New York: Hyperion.

[4] Single loop learning refers to the process where performers modify their actions according to the difference between expected and actual outcomes.

[5] Epstein, D. (2019). Range. New York: Riverhead Books.

[6] Ibid.

[7] More broadly, it is possible that the wolf was invited in, shook things up, contributed to building resilience, but overstayed its welcome. The new leader may have recognized that it was time for the wolf to go, but the wolf would not leave on its own accord, it took an agile leader to escort it to the exit and kick it out. In other words, just because the wolf became negative, does not mean that it wasn’t a good decision at the time it was invited in.

[8] Reivich, K., & Shatté, A. (2002). The Resilience Factor. New York: Broadway Books.

[9] Meta commenting is commenting on what you are speaking about. It can provide context and shared understanding of intention for the speaker and listener.