Food Not Bombs is a 30-year-old global movement. Initially based in Massachusetts, US, the grassroots organisation has now spread worldwide, working to unite and care for people by feeding them, and maintaining an ethos of anti-poverty and non-violence. In recent years, the Yangon, Myanmar sector of the Food Not Bombs movement has become well-known. Mohawked, black-clad and silver-studded, the group spends their time recording and performing punk music, and caring for Yangon’s homeless community. Recently, they have also developed plans to set up a school for children living in the city’s slums.

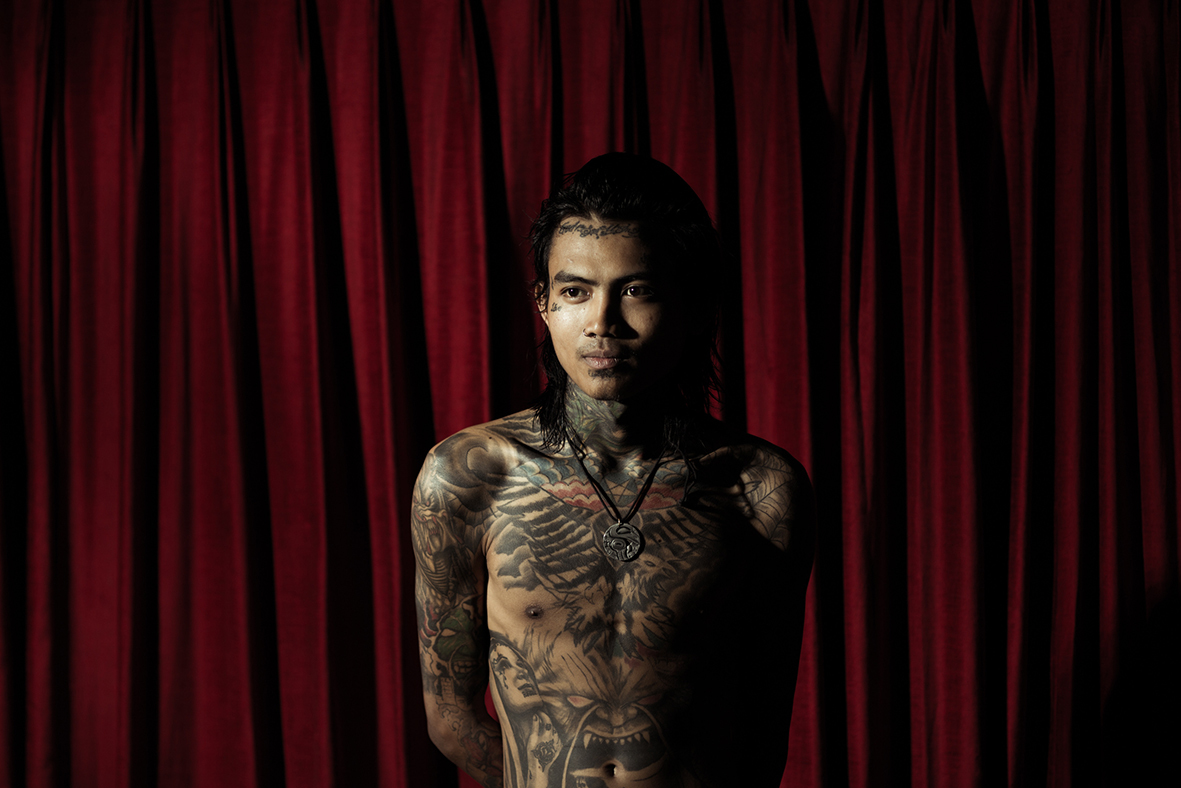

Nico Djavanshir’s series Punk, Love and Kindness follows Yangon’s punks through their daily lives, in the hopes that his work can shed light on their own. The series combines our shared values of individuality, community and unity, and embodies the aims of Portrait of Humanity; we see the subjects with their families, singing into microphones, teaching groups of smiling children, and sometimes campaigning for the Food Not Bombs movement. “I wanted to take positive images,” says Djavanshir. “We’re used to seeing tragic work that makes you cry, but I want to create work that touches people in a different way.”

Having performed as a musician himself, Djavanshir has spent much of his career as a photographer taking portraits of other musicians. Punk, Love and Kindness marries many of his interests; “Photography is a good way to show what is happening all over the world, in different places,” he says. “In Indonesia, when some punks are caught by the government or police, they are given a bath, shaved, and put in jail, and people try to clean them in a religious way.” Djavanshir hopes to break down people’s stereotypes by showing punks in a new light. “There’s this idea that they are antisocial,” he says, “People are shocked to see people with tattoos on their faces, and punky haircuts, giving to people who are very poor.”

Those leading Yangon’s Food Not Bombs chapter are members of a local punk band called Rebel Riot. Their interest in activism comes partly from their music; they realised that while many of their lyrics were about their desire to change the system, there was more they could do to really help. This was combined with Yangon’s increasingly serious problem with homelessness. As rent began to soar following a barrage of foreign investment after the 2010 general elections, and salaries remained low, more and more families lost their homes. “In the slums, you see children who are about eight years old holding small babies,” says Djavanshir. “It’s very sad to see.”

“The punks who organise Food Not Bombs do not have much themselves,” Djavanshir explains. “They gather every Monday under a bridge and give out food to the people living on the streets, the kids from the slums, and those earning a low income.” When shooting the images of the punks, of whom there are about 30 helping on any given week, Djavanshir was overwhelmed by their kindness. “Sometimes they play music for the kids, and tell them stories. They speak very kindly to everyone.”

The punk movement first arrived in Yangon in 1997, uniting an oppressed youth with its powerful modes of expression. An underground network of punk bands began to evolve. In 2007, a second wave broke out after The Saffron Revolution began, and thousands of people protested across Myanmar against repressive military rule. “People are always strangely shocked to see that there are punks in Asia,” says Djavanshir. “I just went there to take pictures of lots of great people doing good things in the street.”

Do you want to be part of the movement? Together, we will create a Portrait of Humanity. Enter before 8 January 2019.

Written by Sarah Roberts

Originally published at www.portraitofhumanity.co