How an unexpected act of kindness can come back in an unexpected way.

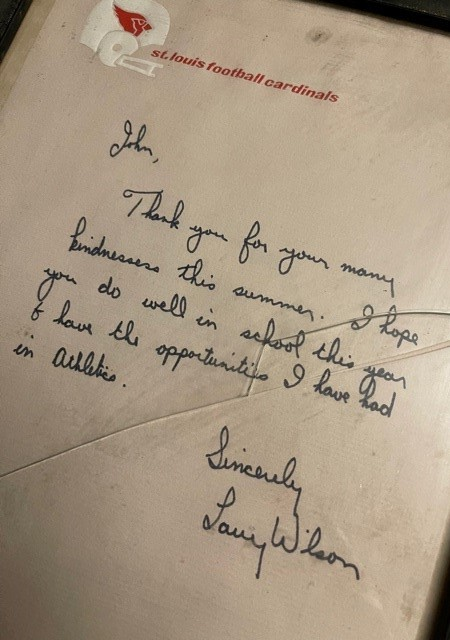

One September Saturday morning in 1969, my Dad and I got in the car to drive to the Five and Dime to buy a frame, one suitable for a letter I’d just received from my idol, Larry Wilson. It was a two sentence letter: “John, Thank you for your many kindnesses this summer. I hope you do well in school and have the opportunities I have had in athletics.” Simple, thoughtful words… and to me it was as meaningful as any letter I’d ever received. Of course, at twelve years old, I hadn’t received a whole lot of letters. We bought a black wooden frame and after slipping the letter under the glass I bent the little metal latches to hold it in place with a piece of cardboard behind it. When we got home I hung it on a nail next to my bed.

Then in the prime of his career, Larry would later be inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame as the greatest safety who ever played the game. He was the first to attempt, and then perfected, the “safety blitz”: storming the quarterback by surprise from deep behind the lines. They called the play the “wildcat,” and Wildcat Wilson became his nickname. He made up in intensity for his relatively small size. The New York Times later reported that at one of his eight Pro Bowls, “Wilson went to shake hands with Y.A. Tittle, the Hall of Fame quarterback who was on the receiving end of more than a few of Wilson’s safety blitzes. ‘If I’d known you were this small,’ Tittle told him, ‘I’d never have been that scared of you.’

I met Larry in the course of doing the first job I ever had. That summer I worked for the St. Louis Football Cardinals. This was long before they moved to Arizona, back in the day when NFL teams made their summer training camps at outposts far from the distractions of home. I came into the job by sheer luck. My family home in Illinois had a backyard patch of woods with a path that twisted through a hole in a chain link fence protecting the perimeter of a football field. Back then the Cardinals did “two-a-days”—a morning practice and an afternoon practice—on that field, all through July and August under a broiling Midwestern sun.

Each morning when practice started I’d sneak through the fence and hang around on the sidelines watching the Cardinals practice. At first I didn’t think anybody noticed me, but it turns out that a kid with no shoes and a shock of white hair got noticed by a few people including the equipment manager, a friendly Midwesterner named Bill Simmons, who one day asked me if I’d mind picking up the towels strewn around the sidelines. He asked my name, and I told him that my real name was John but my friends called me Mudball. That got a laugh.

Pretty soon I added shagging punts to my towel duties, which meant chasing balls during punting practice and running them back to the punter. That was fun, but my biggest break came when I was asked to work on “valuables.” The “valuables” job meant sitting at a desk in the locker room to collect the items each player wanted locked in the safe during practice. The system included a boxful of green canvas bags with drawstrings, each one with a number stenciled onto the front of the bag. The numbers corresponded to the jersey number for each player. Mornings would start with each player approaching the desk. He’d give me his number, I’d give him the bag, then he’d load it up usually with a wad of bills in a money clip, a watch, car keys, and sometimes a chunky ring. I’d put the bag in the safe behind the desk, which was locked up before practice and at the end of the day the ritual was reversed, with each player coming back to collect his things.

The beauty of the valuables job was that I got to talk with each player individually every day. At night I would study old programs and football cards to memorize the face, name, and number of every player. Pretty soon I was able to greet each player by name and pull out the right bag without having to ask what their number was, which usually generated a laugh and often a high five. There was a lot of banter and along the way I was fascinated to check out the players’ valuables: what kind of watch they wore, what kind of car they drove, and how much money they carried around. For a 12-year-old, it was high entertainment.

Nobody was nicer to me than Larry Wilson. He’d ask me what I was studying in school, what sports I liked, things like that. It was always about me, never about him. A few weeks after training camp ended Larry’s letter arrived in the mail. I was blown away by the fact that such a mega-star would take the time to write a handwritten letter to 12-year-old me. It was just like him. He was kind to the core.

When you’re twelve, it’s hard to repay someone for a nice gesture like that. It took me 50 years to find a way to do it. Earlier this year, after coming across Larry’s obituary in the New York Times, I wrote a letter to his widow, Nancy Drew Wilson. I took a photo of Larry’s letter from 1969, still in the black frame but with a crack in the glass now, and slipped it into the envelope. “Surely this is the most random letter you’ll receive about Larry,” I wrote, “but I wanted you to know how much I appreciated his kindness more than 50 years ago when I was a kid.”

A few weeks later, Mrs. Wilson’s reply arrived, written in a beautiful cursive. It said: “Your kind note and wonderful letter from Larry really made my day. It is the most special correspondence I have received. Stories like yours will keep his memory alive for me and others.” She told me that Larry would have been a teacher if he hadn’t joined the NFL, closing with “My heartfelt thanks. Fondly, Nancy Wilson.”

Larry Wilson inspires me to this day. He was a guy who found the time to say thank you, something that most of us who live busy lives tend to forget. Luckily, it’s never too late.