Losing your job for any reason is tough. Being unemployed in the chaos of this coronavirus pandemic makes it even more challenging.

I’ve lost my job three times during my career in corporate America. Fired twice, laid off once. I went through phases of fear, anger, resentment, anxiety, depression, hopelessness, physical illness, financial hardship, shame, and guilt, for many months at a time. The climb back into full balance and acceptance sometimes took over a year.

I had to claw my way through each situation. It was hard work, and it didn’t seem to matter that I practiced meditation regularly or had done mental strength training as part of my tennis career.

My knowledge about change management theory or the archetypal pattern of learning described in Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey didn’t make me immune to the psychological, emotional, physical, and financial difficulties either.

Was I a slow learner? Did I enjoy wallowing in my suffering, or was I terrible at adapting to change? No. My reactions to losing my job were completely normal.

Here’s what I learned about how to bounce back.

When I Lost My Job, I Lost My Identity

Suddenly, whatever my business card said, no longer applied. If I’m not the VP of Sales anymore, who the hell am I? That was a mind-bender. Within a matter of hours, instead of getting hundreds of emails a day, I was getting none.

My status didn’t exist anymore. I was no longer “important.” Most colleagues simply went about their business as if I had never been there. Very few reached out to see how I was doing. I thought, Is this what it’s like when you die?

My amygdala (reptilian brain) was now in overdrive, going into defensive mode, telling me my life is at risk- doing precisely what it is supposed to do: protecting me from threats. Losing your job is undoubtedly a significant threat.

The Neuroscience of Social Behavior

David Rock, Co-founder of The NeuroLeadership Institute in his brilliant essay, “SCARF: a brain-based model for collaborating with and influencing others,” says, The perception of a potential or real reduction in status can generate a strong threat response. Eisenberger and colleagues showed that a reduction in status resulting from being left out of an activity lit up the same regions of the brain as physical pain (Eisenberger et al., 2003). While this study explores social rejection, it is closely connected to the experience of a drop in status.

Mr. Rock goes on to explain that there are five aspects of human social experience: Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness. He says that the underlying driver of our behavior is the deeply imbedded desire in our brain to reduce threat and increase reward or positive experience.

The Five Aspects in the Context of Job Loss

1.Status– loss of identity, loss of value in the eyes of others, and shame associated with not having a job, being unemployed, or furloughed.

2. Certainty– having no idea what the future holds, and dealing with questions like: will I get unemployment, how long will it last, will I get my job back, how long will I be furloughed? (Not to mention the uncertainty of not knowing how long the lockdown will be in effect or what the future will look like post coronavirus).

3. Autonomy– loss of control over the current situation. Not being able to support yourself or your family financially, and not being able to maintain regular daily routines, which now include not going shopping, visiting with friends, attending, or playing sports, or going out to eat.

4. Relatedness– Not being part of the organization and being eliminated from a social network (your work tribe). Finding yourself on the outside looking in. Work relationships fractured.

5. Fairness-Feeling singled out when the organization still employs other people.

Any or all of these trigger a threat response from the brain, so it’s no wonder that losing one’s job can send us into a tailspin.

We are dealing with all five when we lose our job.

The brain is screaming; my life is in danger.

Psychiatrist Elizabeth Kubler Ross wrote about the five stages of grief (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance) in On Death and Dying. Author William Bridges outlined three stages of transition (endings, neutral zone, and new beginnings) in Managing Transitions.

There are certainly differences between the two theories; however, they both describe that we go through predictable patterns when dealing with significant and traumatic change. For anyone going through loss and grief, it’s beneficial to understand the process you will likely go through.

My experience is no matter what those stages are; we need to make good choices to reach the acceptance stage, the new beginning, where we have learned, matured, grown, and have found our balance again.

If we don’t make good choices, we linger in the process and potentially get stuck in resentment or bitterness.

Here are some ideas that can help you make good choices as you face the challenge in front of you.

My Learnings

- I’m a human being, not the title on my business card.

As I went through two of my three transitions, I struggled mightily with this one. I discovered I was deeply attached to my work identity. I managed teams who looked to me for guidance and support, had long term positive relationships across the organization, was proud of what my colleagues and I were doing had accomplished.

Being a leader of a team wasn’t just a job for me- it was something I loved and enjoyed. I was very mentally, emotionally, and psychologically invested- always on, working many nights, weekends, and on the road a lot. In fact, I had allowed my job to become who I was rather than what I did professionally. Workaholic? Yes.

Gradually, I felt my mental attachment to my role dissolve. Honestly, it was one of the most challenging parts of the process. I knew from my meditation practice that I had to peel off the layers of identity and get down to the essence: I am not my title. I am a human being, and I need to get back in touch with who I am.

The process was painful, and for me, and it often took months to disconnect from my corporate identity. There were reoccurring dreams with the key players responsible for my dismissal. There were replayed conversations in my head and endless “what ifs.” I felt like I was shedding my skin, my mask, and rediscovering who I was. Ultimately that served me well. Getting there was just not fun.

–What I did: Shifted the focus from “doing” to “being.” Translation: slowed down, stopped being a workaholic, spent time in reflection, and reconnected to the real me.

2. Focus on what I can control.

We always have a choice regarding how we behave. I knew I faced a challenge during each one of my transitions, and I knew the way I responded would determine my future. I could feel sorry for myself, or I could pick up the pieces and move on, which is what I did.

During one of my transitions, I started morning journaling, meditated regularly, read inspiring books, and started a blog, writing ten articles in six months.

I set small, achievable goals. I felt my confidence grow when I accomplished something. For a job search, I made a list of all the people that I knew and reached out to each one, a minimum of five per week. I had many conversations and built some long-lasting relationships.

If I went to an interview, I prepared well, which was in my control. I focused on doing my best, no matter the outcome. There was a time when I felt a bit desperate. It’s not attractive if that leaks out. I recall a few interviews where the desperation must have been wafting off me like cheap cologne. I didn’t get called back. I was disappointed, and all I could do was try to learn from the experience and move on.

-What I did: Worked on my attitude, created a plan, and took action.

3. Let go of resentment.

Resentment is defined as bitter indignation at having been treated unfairly. I certainly had a bad case of this once. It’s a nasty state of mind where you want to do things you’ll regret later, like write an email to the people that sent you packing and tell them off.

Go ahead, write the email, just don’t send it. I know people that have done this, and they say it was cathartic and helped them move through resentment into forgiveness and acceptance.

At first, I recall demonizing the people that let me go. My mind made it very personal. They did something to me and should be punished! This attitude is the classic victim, and the world is out to get me, mindset. Remember, it’s a phase, a place you are visiting. You don’t want to take out a long term lease on it.

-What I did: Stopped being a victim and played the cards I was dealt with the best of my ability.

4. Focus on learning and growth.

I shifted my mindset from this really sucks to I have an opportunity to learn and do something new. I knew that my dark night of the soul would lead to a new and better chapter in my life if I continued to make smart choices regarding how I behaved.

I visualized the past as a room with the door closed and saw another door open to a brighter future. I stood in the hallway between these two doors with a choice: I can see my situation as a disaster or an opportunity to grow and learn. I chose growth and learning.

I defined my reason for being, my Ikigai, (a Japanese word meaning “reason for being”). Ikigai has four components: That which I love, that which I am good at, that which I can be paid for, and that which the world needs.

I wrote down the answers to these four questions and drew it out on paper. Then each morning, I imagined myself doing and having exactly what I wanted. I was practicing active visualization, a powerful method of creating desired outcomes. It has really helped me through each transition.

-What I did: Defined and visualized what I wanted in the future.

5. Be patient.

While conventional wisdom says patience is a virtue, I often found it very difficult to practice. I wanted things to operate on my timetable, and yet, life doesn’t work that way. With no clear end in sight, I simply had to work on my mindset and stay as optimistic and positive as I could. Anything else was out of my hands.

In 2009, I knew I had serious work to do, given the economic climate and my age. Rejection from one interview after the next didn’t help either. I was hanging in there. The self-talk poured in: you’re 55 years old, no one wants to hire you. You’re done, pal. I just kept at it, accepting it might take more time than I’d like to find employment again.

I’ve been through long job searches before, but doing this during the recession proved to be a very tough challenge. Given this pandemic and the significant uncertainties that exist, regaining employment will likely be an even steeper hill to climb — all the much more reason to be intentional, planful, and patient.

Eventually, in 2011 I reconnected with a former colleague who was part of my networking effort and took a job where I was overqualified. Within a year, I was promoted back into a leadership role. I was on my way again and deeply grateful.

-What I did: Made consistent effort and focused on the process, not the outcome.

6. Know and manage your weaknesses. It’s easy to get lost.

Self anesthetization became my best friend at various times. The mindless distractions took over: binging on the computer, TV, drinking, and unhealthy eating. There was a time when I needed an extra recycling bin to handle all the empty wine bottles.

I had my bouts with boredom too, masterfully described by couples therapist Don Rosenthal, in his book The Uncharted Journey, as the experience of being uncomfortable with one’s present reality and seeking distraction to avoid the discomfort.

He says. “When I allow myself to be bored, I see it as a “No” to what is. This moment is felt to be without value, except insofar as it can get me quickly to the next moment where the mind believes my satisfaction lies.”

Staying very present and living consciously in the moment is undoubtedly tricky when you don’t like your circumstances and are not fully engaged in meaningful work.

I knew, to manage boredom and not self medicate, I needed to stay active. I created projects around the house, started a local networking group, (could be done virtually right now), and spent time studying and reading.

I have to tell you; there were times when I didn’t do well on managing boredom. My impulses sometimes got the better of me; however, when they did, I learned to be kinder to myself and forgiving.

If I caught myself binging, I wouldn’t berate myself; I would say, ok, time to move on. I watched my language and eliminated “I should” from my vocabulary. Instead of focusing on what wasn’t working, I put my attention on what was working well and celebrated any small achievements.

-What I did: Stayed active, leaned into my strengths, and accepted it’s okay to be bored at times.

7. Don’t buy into fear.

Fear is like any virus. It needs to feed on something living. Without a host, it can’t exist. I could feel fear hovering about, looking for a way into me. Even the smallest fears, were carriers of dark energy, like miniature trojan horses, who disguised themselves as harmless thoughts. If I paid attention to one of them, I was simply welcoming it into my inner world, where it created doom and gloom.

I knew that fear could not exist in me if I didn’t listen to it. I found I needed to be hyper-vigilant to any negative self-talk. If I heard any, I’d turn away from it, or I would reframe it. Example: “Everything is getting worse.” Reframe: I am facing a big challenge, and I can do it.”

Fear, like darkness, cannot exist in the light. I kept the lights on as much as I could.

-What I did: Practiced meditation, reframed negative self-talk, used positive affirmations, and prayer regularly.

8. Ask for help.

I hired a life coach after the first time I got fired. I was quite a miserable person at the time, and the coach did everything he could for someone who was utterly lost and confused. I tried to put into practice the coaching and daily routines he suggested. They did help; it just took time.

Instead of a coach, friends that will support and challenge you are invaluable. There’s nothing like the care and love that can come from someone who can see what you can’t and call you out on what needs to be said.

Without a meaningful connection to those you value and trust, it’s too easy to contract and withdraw when things aren’t going well. I learned I had to make an effort to reach out, despite how difficult that was.

-What I did: Reached out to friends and colleagues.

9. Balance realism with optimism.

This principle, known as The Stockdale Paradox, was made famous by Jim Collins in his masterpiece Good to Great, where he described the philosophy of Jim Stockdale, former vice presidential candidate and a Vietnam prisoner of war who was tortured repeatedly over seven years.

Stockdale said, “You must never confuse faith that you will prevail in the end — which you can never afford to lose — with the discipline to confront the most brutal facts of your current reality, whatever they might be.”

I had to confront my brutal facts: I did not have a job, was draining my savings, and was struggling through the transition process. I also had a strong track record and reputation in the industry and many useful contacts.

My faith believed that I would come through this, and everything would be ok. Understanding both principles really helped me.

-What I did: Nevergave up.

10. Build Resilience.

Cy Wakeman, NY Times best selling author tells this story: We did this great experiment that I used when I was teaching a college course. We put third and fourth-grade children in a gym, turned the lights off, and watched how they behaved. Then we put only adults in a gym; we turned the lights off and watched how they behaved. The difference we saw was amazing.

When the lights went out on the adults, they sat quietly, isolated, without reaching out for one another. They waited for one or two innovative people to come along and figure out what might have gone wrong. They were so well behaved, they hardly moved from their spot.

When the third and fourth graders experienced the lights going off, they moved from their spot and reached out to others. It was hilarious! They were trying to figure out who was beside them by feeling each other’s hair, and asking their teachers who might have a cell phone.

They were thinking about reaching out and connecting with others. They were very noisy and very extroverted. They were grabbing ahold of others, sticking together, looking beyond themselves. You see, while the adults sat alone, quietly persevering, the children were resilient.

Perseverance is “the continued effort to do or achieve something despite difficulties, failure, or opposition.”

Resilience is “an ability to recover from or adjust easily to misfortune or change.”

Isn’t there something loving and intelligent about small children reaching out in the dark to each other?

Are we not in the “dark” when we lose our job?

-What I did: Accepted my circumstances and practiced gratitude for what I did have.

Two Practical Exercises

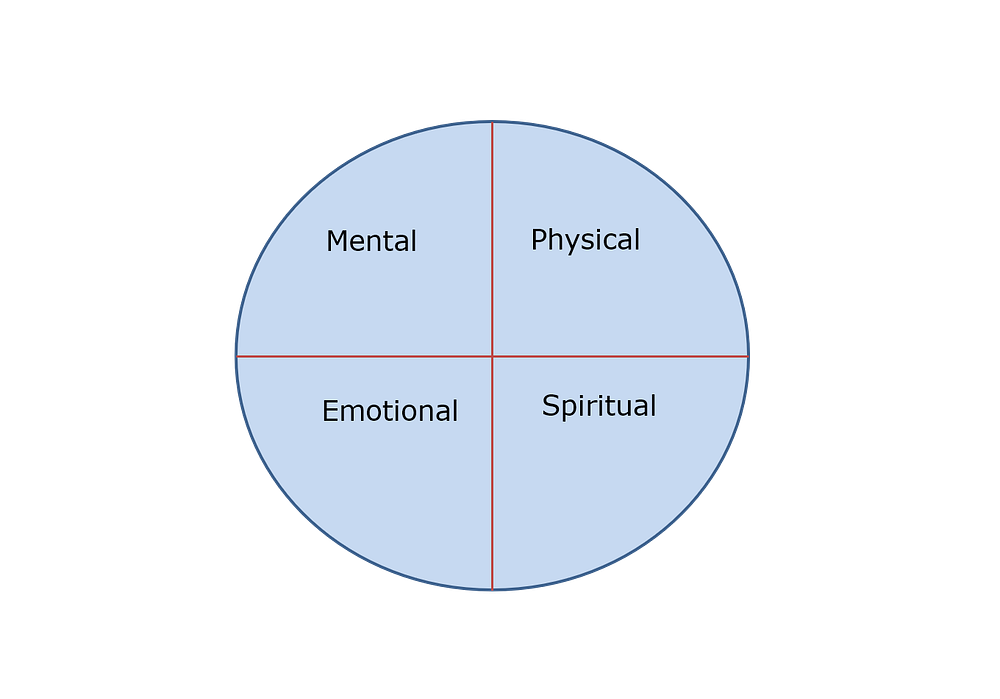

- Think of yourself in four dimensions: mental, physical, emotional, and spiritual.

Ask yourself these questions for each dimension and write down the answers. Share them with someone close to you and have a conversation.

What am I doing well? What’s not going so well? What could I do differently? Do I have the will to do something different? What help or resources might I need?

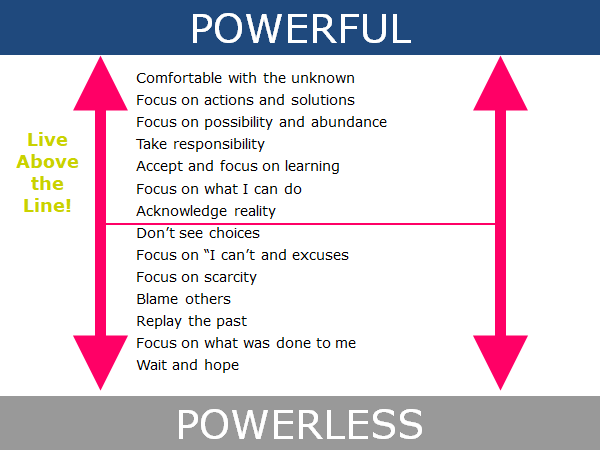

2. Read the statements below. Are you living above the line? If not, why and what would it take for you to live above the line?

And, let’s remember what Nelson Mandela said: “It’s always impossible until it’s done.”

First published on Medium