At 18, Leon Wilson was getting quite a reputation for selling cocaine in the Pierson neighborhood on the North Side of Flint, Michigan. His name started ringing through the streets, eventually reaching Leon Parks. His dad.

Father and son hadn’t seen each other in about six years. When they reunited, Leon Wilson expected an explanation for his dad’s absence. He braced for a lecture.

It turned into a business meeting. Leon Parks wanted to buy some cocaine. If he got a good price, he’d bring his son more clients.

“That,” Leon Wilson said, “is what made my heart harden.”

With his illegal lifestyle validated – honored, even – Leon dug in deeper. He worked his way up to a supplier. A turf war broke out. Masked gunmen shot out the windows of his car from behind; when Leon turned to fire back, he took bullets in his head. He’s now deaf in his left ear and has shrapnel in his skull.

After a month in a coma, Leon sought revenge. Police got to him first. They raided Leon’s home, handcuffing and pinning down his mom, two sisters, a brother, an uncle and several nieces and nephews.

Leon pleaded guilty to drug and weapons charges. On the first day of his 12-to-20-year prison sentence, he saw the body of an inmate dangling from a higher floor. Leon would soon witness things far worse than suicide.

What really got to him were the phone calls to his mother, siblings and grandmother. In their voices, he heard the pain he caused them. It echoed in his mind during the 22 hours a day he spent on lockdown.

“That,” he said, “is what softened my heart.”

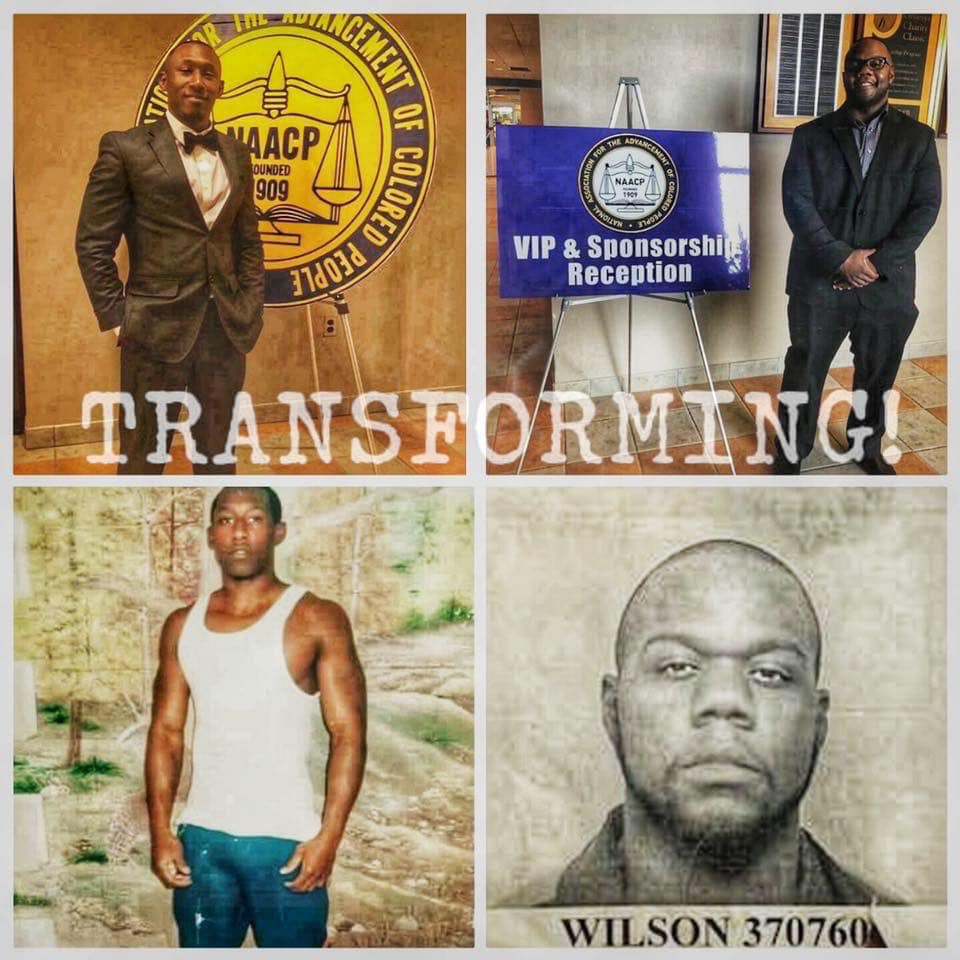

Empowered by a new outlook, a new religion and a new name, Leon Abdullah El-Alamin left prison and refused to become another statistic. Along with a friend from prison, Leon created the M.A.D.E. Institute, an organization that is giving hope and opportunities to felons looking to improve themselves and youths at risk of going down the wrong road.

Essentially, they want to turn people like them into … well, people like them.

***

Leon was a good kid.

Despite his dad’s errant ways and his mom’s struggles with drug addiction, alcohol and abusive relationship with men, Leon found refuge with his grandmother, Mattie Wilson – or, as he called her, Granny. For years, Sundays were spent at the Baptist church in the morning and at Granny’s dining room in the evening.

He wasn’t completely shielded, though. One day when he was around 12, a drug dealer came into his home waving a gun and looking for money he was owed. Granny bailed them out.

Leon avoided gang life in high school. Then he graduated and couldn’t resist the lure of “guys with fast cars and fast money.”

Part of the problem was the lack of a father figure. Granny’s husband had provided it, but he died.

When dealing drugs brought Leon Parks back into Leon Wilson’s life, there might’ve been a chance to straighten him out. When it went the other way, Leon Wilson doubled down on snorting cocaine and spending his weekends in limos filled with booze, prostitutes and what he now calls “rented friends.”

Everything changed the day police raided his family home. He took a plea deal and, in 2003, headed behind bars.

***

In his cell, he cried. He cried and cried until he ran out of tears.

“I began reflecting on the damage I had done,” he said. “I began searching for answers.”

At 300 pounds and detached from his Christian roots (“The streets became my religion”), Leon began exercising and reading during the 22 hours a day he spent in his cell.

During his minimal free time, he noticed the serenity of a lifer from Detroit. What was his secret?

Mubarez Ahmed found salvation in Islam. Soon, so did Leon. After months of reading and praying, Leon DeWayne Wilson took his shahada – his declaration of faith – and adopted new middle and last names.

“Abdullah means ‘servant of God’ because I was striving to be righteous and connected to my Creator,” he said. “El-Alamin means the ‘trustworthy one’ or ‘the leader’ because my word is my bond.”

Mubarez was sent to another prison, where he found another disciple. He told the man about Leon. That man wound up in the same prison as Leon. They began praying together. When Tim Abdul-Matin realized this Leon was that Leon, their bond tightened.

Photo courtesy of Leon El-Alamin.

***

In July 2010, at age 30, Leon walked out of prison a free man. Tim got out the month before. They pushed each other to continue exercising, reading and praying to avoid falling into their old, bad habits.

It was tough. Jobs and schools turned them away; no second chances there. They finally landed in a federal program to rehabilitate houses. A year later, an unrelated scandal left them searching again.

Leon went to an event at the Flint Islamic Center. Hearing fundraising pleas for Muslims causes overseas, he took the microphone and respectfully said: “You guys earn your money here – what are you doing to help people here?”

The message struck a chord with neurosurgeon Jawad Shah. He hired Leon and Tim and gave them office space to start 3Rs, an organization seeking to refine, reform and rebuild people across Flint.

They struggled to gain traction. The problem: Their office was on the South Side, their target audience on the North Side.

Shah became a mentor to Leon. The doctor invested in his pupil, first by emotionally showing interest in his vision, then by purchasing a place for him to make it a reality – a North Side building called the Sylvester Broome Center. That’s where Leon and Tim launched the M.A.D.E. Institute.

The acronym stands for Money, Attitude, Direction and Education, everything the group aims to provide to everyone returning from prison and those seeking to avoid it.

“If you are serious about rebuilding a city or a community, you have to empower people,” Leon said. “From our surveys and what people tell me, I know they don’t want a handout, they want a hand up.”

***

Working with the Michigan Council on Crime and Delinquency, M.A.D.E.’s first big win was landing funding to get 10 people trained in skilled labor. The next year, the organization applied on its own and got $55,000 to rehab a house in North Flint. It’s now used for transitional housing.

The group has turned two more abandoned houses into transitional living sites. M.A.D.E. also provides therapy for mental health and substance abuse issues, an entrepreneurship program and training in green-energy jobs. Leon’s dream is to create a single facility to house all his ambitions.

“We’re very close,” he added. “We’ve gotten the attention of elected officials. If they get behind us, it’s going to be game-changing.”

I’m happy to say that my organization, the American Heart Association, is helping.

We recently gave the M.A.D.E. Institute $100,000 from our new Social Impact Fund, which is dedicating to investing in local entrepreneurs, small businesses and organizations that are breaking down the social and economic barriers to healthy lives.

***

One day in 2014, Leon turned on his faucet and out came yellow, smelly water.

“I’m not a scientist, but I knew that wasn’t right,” he said.

He arranged for donations of bottled water and began handing them out. He got the Muslim community and other faith-based groups involved.

He later set up a partnership with Wayne State University. Folks from M.A.D.E. gathered samples and the university scientists tested it for Legionnaires’ disease, offering yet another example of how connected Leon is to what his community needs and deserves.

“I came back here when I got out of prison because I felt it was only right to help repair what I was part of tearing down,” he said. “Once the full vision of M.A.D.E. manifests, I want to be the poster child for lifting distressed communities. If it can work here, it can work in other places, too.”