An oilfield worker who read the dictionary for fun and called us from the field to go look at spectacular sunsets, my father wove wonder and awe into our daily lives. Especially that one night …

By KC Compton

Dad’s sense of whimsy taught us to view the world with wonder.

Throughout my childhood I learned to listen for a particular sound that signaled the end of daytime and the official beginning of the evening – the squeal of the brakes on my dad’s work truck as he rounded the entry to our subdivision from the highway blocks away. If for some reason my sister Donna and I missed hearing that faint sound, our two little Pomeranians would easily pick up the cue and begin dancing and whirling at the front door, signaling that their favorite person was about to come in, scoop them up (all the while reassuring them that, “I hate dogs. I just hate the doggies,” in a voice that, because they couldn’t understand words, sounded exactly like cooing) and hold each of them “sitting up pretty” in the palm of one of his beefy, work-roughened hands.

He usually would spend a few minutes greeting the dogs and my sister and me, his “darlin’ dodders,” who within seconds of his coming through the door in his khakis redolent of crude oil and other oilfield crud, would be wrapped around his legs, as eager as the puppies for some Daddy love. He would hug each of us individually for a minute – his special treat was “whuskering” our necks with his 5 o’clock shadow, which made us squeal with mock horror – then make his way to the kitchen where Mom would be ready with a cup of coffee and whatever treat she had made him that day. They would sit at the kitchen table – children were not invited to this tête-à-tête – and debrief his day. Then, after 30 minutes or so, he would go shower while Mom – with our assuredly valuable assistance – finalized dinner.

One of the few exceptions to this routine occurred when I was 8 years old, a fine, clear October evening when Dad came in with a bustle to his step — markedly different from his usual amble — and told us all to get our jackets and meet him in the back yard in 15 minutes.

This was bizarre. We spent hours in the back yard all summer, but this was autumn, with night quickly falling. More uncharacteristic behavior followed, but our dad was tight-lipped and purposeful as he dragged out the huge cast-iron skillet which had one purpose: popcorn. But popcorn was for Sunday nights while we watched the Ed Sullivan Show. This was a Friday. What was going on?

Mom appeared with the two big blankets we only took on picnics and lead the way out the back door. The puppies followed, dancing and yapping, Donna and I pulled our jackets on and followed our teenaged sister June, who by now had joined the party, outdoors – the four of us collectively mystified by what mischief our father had gotten up to.

In a minute, Dad showed up with a large bowl of freshly buttered popcorn and then told us to lie down and watch the sky. He pointed out the constellations, which we already somewhat knew, thanks to his tutelage. Suddenly, he said, “There it is!” He put his arm around Mom and directed her gaze to a blinking light at about 11 o’clock overhead. My sisters and I peered and peered and finally we saw it too. A blinking light making a slow arc across the star-splashed black velvet sky.

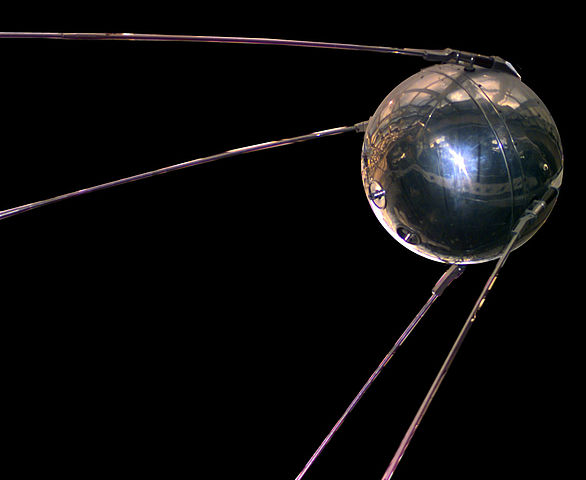

“That,” Daddy said triumphantly, “is Sputnik, the satellite the Russians just launched. That is man-made. Humans are in outer space now.” The awe and wonder in his voice directed our eyes for a closer, more appreciative look, and we all sat there mutually astonished, wordlessly eating our popcorn and watching as the tiny light, laden with human expectation, blinked its way across the star-spangled sky.

My childhood was filled with similar Moments of Wow, courtesy of my father, who was one of the most inquisitive, whimsical people you were ever likely to meet. He wondered and I learned to wonder, too. To be more precise, I learned it was completely possible and even desirable to keep wondering even as an adult. Most of what babies do is wonder, but that gets squelched early and often for most of us. With my dad, it thrived. I’m proud to say I inherited his playfulness and capacity for being blown away by how incredible our world is.

The major celestial events I showed my kids didn’t impress them quite as much. When they were 13 and 8 or so, I poured a thermos of hot chocolate and rustled them out of bed and into my elderly Toyota to drive into the country outside Albuquerque for a look at what I think was Halley’s Comet. My memory now is as dim as the comet was — underwhelming, as celestial events sometimes end up being. My 13-year-old son summed it up pretty well when he rousted himself out of sleep long enough to peer up with one eye open. “It looks like a damp Q-tip, Mom.”

I had to give it to him, it pretty much did. But at least we made the effort. At least we were out there, just in case it turned out wonderful. My father would have approved. He would have brought popcorn.