Eric Schleien (ES): All right John, so thank you for taking the time to do this interview. I wanted to talk with you about some of the frameworks and principles that are brought up in “Principles of Power”. Some of these principles are principles and frameworks that you invented, and, [I] wanted to take a deeper dive into them so that when they’re brought up later in the book, readers will have a better understanding of what I’m talking about. Does that sound good?

John King (JK): That sounds great.

ES: Ok perfect. Let’s start with the cultural map. In the book, I mention things like Stage 2, Stage 3, [and] you’re quoted a few times where you talk about that and its relationship to givers and takers, push and pull, and flow. Can you give us a little sense of that world and what you mean by the different cultural stages and how that interacts with some of the other models that you’ve invented?

JK: Sure. The cultural map is a diagram that shows how people group together and how they talk when they are working together. It’s designed for groups, [and], it’s designed for looking at culturally how people work together. The backup on that is how they connect or clump up together. What I noticed was that we live in a culture where it’s pretty much about your individual effort, and therefore, people are not very good at forming partnerships. When they do form partnerships, they form them in a hierarchical manner, that is to say as a junior to senior in the partnership, which is in my world, is not actually a partnership. Mostly what we’re trained to do when we work is we work inside of what is called a zero-sum environment. A zero-sum environment is where somebody wins and somebody loses. The purpose of the cultural map, and the structural map that goes with it, is to show people exactly at which point things tip-and-change to the next level of the zero-sum game, and, then where the zero-sum game becomes bankrupt if you’re trying to accomplish something at the level of group, and, at which point there needs to be a mental shift into something called a non-zero-sum positive outcome. In a zero-sum game, there’s a winner and there’s a loser. I win you lose and we can kind of count it. I win by 3 points you lose by 3 points, the sum is 0. In a non-zero-sum game, it’s actually a participation in which we’re all in the same game together and we all win together or we all lose together. My purpose was to have people look at this, see how they talked, and how their language actually impacts whether they’re in a zero-sum or non-zero-sum game, and, what level or stage—I called it a stage—of the game that they’re playing it—and at which point—if they happened to find themselves in a non-zero-sum game, what level they are there. And what we noticed—I didn’t know this going in—what we noticed was when people go from a Stage 3 zero-sum game which most everybody knows how to do it to, and go into a Stage 4 non-zero-sum game, their productivity goes up by a factor of about three times to five times. And so, I became interested in that because I’m interested in productivity. I’m interested in partnership and I’m interested in “how does partnership affect productivity”, and, I’m interested in the role that language and structure play in productivity and partnership.

ES: You mention there are five stages of culture, five ways that people organize themselves in groups.

JK: Yes.

ES: Can you say a little bit more about that?

JK: Yes. In ascending order, people are more effective, that’s the first part of this. At Stage 1, there’s only about 3% of the people that are organized at Stage 1. It’s a kind of a place where criminals are, and, it’s an area that we call undermining. People who are in an undermining [relationship to their environment] and alone [in their environment] because it’s a very alone sort of thing are at Stage 1. The next level up is something like— we experience this on a bad day—at Stage 2. Stage 2 is ineffective. When I notice that I’m not really being effective at what it is that I’m committed to, one of the things that I notice is that I am not really well connected. In fact, not connected at all to the people around me. I’m kind of there and I’m amongst them. But, I’m not connected to them. So at Stage 1, one of the things people at Stage 1 say is: “life sucks”. At Stage 2—it’s a big change—it’s “my life sucks.” I mean, I could see that your life works. I can see that the things you do work well. I can see it’s a great life. I just don’t have an access to participating in it. I’m not connected in a way that I can participate in it effectively, so I’m being ineffective, and “my life sucks.”

ES: To make a further distinction, most people, when they say “life sucks”, what they actually mean is “my life sucks.”

JK: That’s actually what they mean. We tend to speak hyperbolically. And for the most part, very seldom, do people actually get into the true “life sucks” unless they’re in wartime or [involved in] criminal activities, or, they’re trying to bring down the whole structure. But the truth is, that “my life sucks” is kind of the place where you feel ineffective and then we kind of dramatize it.

ES: Right.

JK: Stage 2 is connected by the way, kind of like I say joined at the hip to Stage 3. Stage 2 and Stage 3 have a symbiotic relationship. Stage 2, is ineffective, or you could say “a loser”, at least in this particular point [of view]. They have a point of view that “my life sucks.” Stage 3 is the winner. Think of sports. The person who is the champion is the Stage 3 and what they say is, “I’m great, you’re not, and I have the statistics to prove it.” So they are organized around winning. And if you’re organized around winning, in this particular way, it’s a zero-sum game. The people that you are winning over are the people who are at Stage 2. The trick about this is that Stage 3 does not exist without Stage 2 nor does Stage 2 exist without Stage 3. They live in a comparative world. This is where we form partnerships. But the partnerships are definitely senior and junior. Stage 3 is senior and Stage 2 is junior. What you have is a relationship where Stage 3 is dominating a Stage 2 and Stage 2 is avoiding the domination. It’s a relationship from [Stage] 3, “I’m great, you’re not and I have the stats to prove it”, to [Stage] 2, “my life sucks.” If you think about it just a little bit, you can actually see, when you’re being ineffective and then somebody is actually driving you, managing you, dominating you, what comes along with it is a kind of a glee, a sense of I’m better than you. So how we build our self-image quite often, particularly when we’re young, is we build ourself at Stage 3. It is not just a small thing, it’s a big thing. If you extrapolate this out to companies, it’s: “our company is better than your company”, which is a Stage 3 to Stage 2 sort of saying. “General Electric is better than Westinghouse”, or, you can say politically, the United States often represents itself as better than Canada. And so if you’re a Canadian, you’re in a Stage 2 relationship to most Americans and nobody realizes it because it’s all sort of in the background. So that’s Stages 1, 2, and 3.

There is a shift that occurs at Stage 4. At Stage 4, there is a realization that if I’m going to do something, I need to actually be generating leadership, effectiveness, or empowerment of other people around me. So what I need to put together is, I need to put together a small group or a team. Often it’s 3, 4, 5, or 6 people who are all in the same boat, and, we’re all—you know—paddling towards the same goal. So at Stage 4, it becomes “we’re great”, and, we begin to look at ourselves socially. For the first time for human beings they look at themselves socially. This is where leadership starts. This is where empowerment starts. This is where interesting results begin to occur. This is the beginning of something. This is a partnership. This is, literally, where people form effective partnerships and whereas Stage 1 was called “undermining”, Stage 2 is called “ineffective”, Stage 3 is called “useful”, it’s a useful place, however, Stage 4 is called “important”, and, important at the level of stable partnership and inside of a common languaging of “we’re great.”

Then, if you’ve done the work and put yourself solidly at Stage 4, then opportunities come along. They only come along for groups that are operating at Stage 4. And usually they’re the kind of opportunities that will make history, it will change the game completely. This is what we call a “vital stage” or Stage 5. At Stage 5, this is where team really shows up. Because your little group begins to connect up with somebody else’s little group and somebody else’s little group with somebody else’s little group to form a team. And when we form a team, the language around is generally “life is great”, and what we’re doing is accomplishing off-the-charts sort of results. Most people at Stage 3 think they’re doing Stage 5. Not accurate. When you get to Stage 4, and you do the work around building yourself at Stage 4, you have that Stage 5 opportunity. You actually get to see the remarkable difference between a zero-sum/Stage 3/”I’m great, you’re not”, and, a non-zero-sum/ “life is great”/ Stage 5. But in order to do this, you have to do the work, and you have to do the work with other people. Human beings are social creatures. In fact, they’re ultra social creatures. And so we work best, not when we’re alone, we work best when we work effectively with other people. So Stage 4 is all about effective stable partnerships, and, in Tribal Leadership, the whole name of the game is getting people stable at Stage 4 so that they are ready for the opportunity when it shows up. And it will for people who have done the work at Stage 4. It does not show up for people at Stage 3, and, they end up missing the opportunity and then—I don’t know—be weird about it.

ES: When you say getting people stabilized at Stage 4, do you mean, essentially, having people have their environments be conducive to Stage 4 as opposed to these peak Stage 4, oh we had a moment of partnership then it goes back to the old ways again?

JK: Yeah. Thank you, that’s actually really well thought through Eric. It’s about environment. See the thing is at Stages 1, 2, and, 3 it’s all about me, me, me, and, it’s only about my survival, and it’s all about me winning, you losing, and me getting ahead. However, at Stage 4, there’s a consciousness that: how I win is by making sure that other people win, so, what should become at Stage 4—and this is the beginning of leadership—you become not someone who is out for yourself, but someone who is out to create an environment for other people to perform well. So, it’s about being an ecologist. It’s about being an environmentalist. It’s about really providing an environment. It turns out, generally speaking, if you base your relationships with people properly, which is on merit, it turns out that people are probably pretty good at what they do and don’t need a whole lot of managing, but, they might need some leadership. Leadership—being kind of a code word for: a great environment to work in.

ES: Right.

JK: Google is a great example of it. Because what Google does is hire really smart people and then creates an environment for them to work well together. And as a result, they get off-the-charts kinds of results. This is also happening in our other programs that we see that are the flashy splashy great ones going on. The ones that seem to be passing away are the ones where they are still operating of the old version of “I’m great, you’re not.”

ES: Right, which isn’t that conducive to having stabilized—

JK: Right. Rather than actually having stabilization—it actually presents bullying to say it brutally.

ES: Right, interesting. Can you explain how someone would actually apply these principles—I’m very interested—if you could talk a little bit more about the principle of the triad and how that impacts—and how you can use that principle to impact the environment around you.

JK: Well that was really at the heart of it—I love this question—and it’s one I’ll have to create a little bit with you. But because it’s a little bit abstract here—I could draw it and it would be a little bit different perhaps—but one of the things that I—shock, shock, shock—one of the things that I realized at a certain point in time was that there was a limit to what the individual could actually produce. Then there was something the individual could produce if they were to, in a sense, enslave other people and dominate other people and make other people do it. We call that management. But when I saw—and started looking at extraordinary results at the level of team—when I started that, what I saw was that people had radically shifted their attention from their own survival to the success of the other people they were working with. And when I saw that, I began to look at how do we work together. I asked this question: what’s the minimum number of people in a relationship that has it be stable? I’ve asked that question several thousand times. And the answer that I almost always get is two. But when I ask people where they learned that, for the most part, they don’t know. They point to maybe their parents or they point to some sort of something. But the truth is, it’s a myth, and it’s a myth that we’ve been fed by the social sciences: Sociology, Cultural Anthropology, Psychology. We’ve been fed that it’s about two [people].

ES: How did you discover that [it] was a myth?

JK: I discovered it in a way that was very touching to me. I have a friend who had a beautiful talented son who was being scouted to go to Notre Dame University and he was an athlete and a scholar—very stunning young 15-year-old boy—and, I got a call one day—and it turned out that the boy committed suicide. Shot himself in the head. And, it was such a shock to me because this kid had such a life in front of him—that I began to—I couldn’t get my mind around it—so I went to a whiteboard and started drawing out—I knew him fairly well, and so, I started drawing out every significant relationship that the young man had. And when I drew them out, they came out as triangles, and, I began to look at that and consider that the only way that we are truly stable is when we are in some kind of triangulated relationship. I looked physically across the room—and I have a camera on a tripod—and looked at the tripod and I went “oh! The fundamental structure for stability is at least three anchor points, not two, and maybe I could think from that.” So, I looked at this diagram of triangles, and, I saw that what had happened for one reason or another over a course of several months is that every single triangle that this young man was in—as his network of relationships had broken—they had gone away, they had stopped, they had literally dissolved. And here was a young man who was standing alone—but it looked like he had his family—and his friends, and his school, and everything else—I got everything looked cool but it turned out that it was not so. He had shifted from one school to another school, and, when he shifted from one school to another school—his best friend who had been his friend for life and his girlfriend who he loved—decided they were in love, and, they abandoned him. So his mother and father had kind of gone away from [him], his sister kind of gone away from him, his friends—he gone to a new school—his friends were missing, he was at Stage 2 to begin with, and then all of a sudden, the straw that broke the camel’s back for him was that his best friend and his girlfriend decided that they were in love. Now people don’t take teenagers very seriously in the matter of being in love. They say it’s puppy love. But for them, this is love. This is the real deal. He didn’t have any way to deal with it. So what he did was he stole his parent’s car—you know—hijacked the car and got a couple of buddies, and, went over to his ex-friends house and beat him up. And then the roof fell in on him and everybody around him, including his parents, the boy’s parents, and so on like that, just landed on him. And he was forced to shame himself or humiliate himself in front of the family—both families—to the guy who had been the guy who stole his girlfriend. At least that’s the way it looked in his life. And he was forced to shake his hand. When he did, the guy whose hand he shook—who was 15-years-old also—smiled because he won. And he literally kind of rubbed it in. Then he went home and he was still in trouble because he’d stolen the car, and he’d lied, and he’d done this and he’d done that, and, then a couple of days later, he was found in his parent’s bedroom closet, and, he had blown his brains out. And this was totally shocking. But what it got me to was—that when I drew out the figures on the whiteboard, what I saw was, we are stable when we are in triangulated relationships, and so that became the basis of the way that I look at networking and it became the basis of something that I called triads. Then I saw that when you move from Stage 3 to Stage 4, if you took a couple of people with you, and you did it in such a way that everybody in the triangle was committed to the success of the other two rather than worrying about their own survival—the thing about it is that the building of a triad is a mutual thing.

ES: Right.

JK: In other words, it won’t just work for me to pick you and some other random guy and then be committed to your success unless I’ve got you in a non-zero-sum game with me in which you realize that my success is your success and the other person’s success is your success. The rule is: the one person in the triad is accountable and responsible for the success of the other two. If you looked at it like a triangle, you would say the vertex is accountable for the success of the opposite leg, and, it requires that all three people in the triad are actually on the same boat. And the reason this is good is because it starts to bring up stuff that we start hearing a whole lot about. But we hear it discussed in an ineffective way. For example, this is where values come in. If I take you and another person, we have to be very clear that our values are aligned with each other, and so, if somebody has significantly different values, this is probably not going to work. This is where generosity comes in. Leadership is a generous space. This is where the idea of having the permission of the others comes in. Leadership is a distinction that operates or is granted by the permission of the people being led. So what you’ve got to have is you’ve got to have an environment in which all can succeed and that what you’re there [for], is you’re there for the success of the others in the group. Some people are extraordinarily good at this but not very many—maybe 20% of the population—if they wake up to it. So if I took the numbers and I said 3% are at Stage 1, about 20% is at Stage 2, roughly 50% are at Stage 3 at any given moment—and it’s a very fluid in-and-out thing—Stage 4 is 20%—its an enlightened 20% of people who are interested in the success of something that’s bigger than me—bigger than them. So something that comes in at Stage 4 is something called a noble cause, something that makes it bigger than me, bigger than the three of us, and something that is worthwhile for us spending our time, and our effort, and our money, and our ingenuity on to make happen. This is the—I don’t know—the golden egg I suppose or the Holy Grail of organizational culture thinking. If we can get everybody working, and working happily together in a respectful and honoring way with each other, inside of the same kind of value set, and working on something together that is worth accomplishing together, that’s bigger than us, then we have a good chance of putting ourselves at Stage 4. Otherwise, it just devolves into: I won this round or I lost this round.

ES: Right. So if someone is part of an organization and they notice that the culture is at either Stage 2 or Stage 3, how can they start to begin building triads to move to a stable Stage 4? What are some things to start looking for?

JK: Well, for one thing, listen to the way that people talk and you will find that in some way, shape, or form, people in these particular environments—along the lines of “my life sucks” or “I’m great and you’re not”—and they’re that way with each other—in other words, there’s all kinds of internal competition and a lot of putting people down—it’s often pretty snarky—so one of the things is—if you listen to the language, that will give it to you. Another is, if you take a look at how they organize, at Stage 2, people are disconnected. There in and around the group but they’re not really connected to the group. If you take a look at someone who is sort of drifting and they don’t really seem to have people—except maybe people who talk like they do, which is “my life sucks”—but other than that, they’re not really well connected, that’ll be somebody at Stage 2. Stage 3 is at the center. Stage 3 is the person who considers themselves to be the leader and they may have had five or six people around them that depend on them. They form a hub-and-spoke. So if you think of the “so-called leader” at the hub and you think of the people at Stage 2 as being the spokes—that’s what they do—they’re smart: they put people around them, they lie to them, they tell them that: “I’m going to take care of you,” but ultimately, if you take a look over time, their practice is not to take care of people but to take care of themselves first. And then, if there’s anything left over, maybe take care of a few of the people that are the spokes.

ES: Could you say that those kinds of relationships are more transactional or commoditized?

JK: Yeah absolutely transactional. This is something that, I want to win this game, or, I want to win this account, and, I’m going to do what it takes in order to beat you to do that. Very transactional. The long-term kind of relationships are the ones where we decide: we’re all in this together—and in all of us being in this together—I have to support you—and I’m expecting your support—so that we the three of us, the five of us, the seven of us—think—you know—some more than one—that what we’re doing is—we’re working on something that’s going to be of benefit to each and every person, and if it’s not of a benefit to all of us, we don’t do it.

ES: If you want to move your organization from Stage 2 or 3 to having it be stable at [Stage] 4, you essentially are looking for those people that could be your partners in building those triads. Is that the sense of it? What has been your experience?

JK: Yeah it’s a good question because you would think that you would look at the Stage 3 [people] because they’re a little higher on the food chain. But the truth is, when people are at Stage 3, and they’re winning, there is basically no incentive for them to change. So they’re very difficult to change. What we’re looking for are people who are at Stage 2, but who are bright and who are open and willing to make a change. So—my life sucks—but I could see that it could be better if I was—you know—working with you and you—and we were actually up to something that was going to be a benefit to all three of us. Where you look is you look at the Stage 2’s and you put together—what I’m going to call awake or enlightened Stage 2’s who see that—I’m sick and tired of being in survival, and, I’m sick and tired of being the loser and on the bottom end of this deal, and, what I want to do is I want to actually work my way out, and, the way that I work my way out is in a true authentic partnership with at least a couple of other people.

ES: I would add to that—and tell me your thoughts on this—that there’s going to obviously be some people who are hanging around talking about how “my life sucks” in that environment. They’re not really awake, but you could say, that if you’re in a Stage 2 or Stage 3 culture, that people who are awake—and maybe you could even say—have a commitment to partnership, a commitment to Stage 4-ness in a culture—they’re inherently going to be at Stage 2 in that kind of environment.

JK: Yeah, it’s true. There’s an ontological rule that: you have to have a breakdown before you can have a breakthrough. Stage 4 is a breakthrough place. It’s a breakthrough in several ways. It’s a breakthrough because it’s no longer a survival place. It’s a place where you’re actually generating abundance. It’s a breakthrough because it’s no longer singular, it’s social. And it’s a breakthrough because, I have this realization of: working with people is actually going to work for me, so that’s a breakthrough. And when human beings went from—the one individual to the team player, the collaborator—that’s when the whole conversation called human being began to move forward rapidly. For example, you take other primates—chimps haven’t learned this. So they live in a hierarchical world and they’re brutal. It’s a brutal world, a brutal competitive world, and it’s all about survival. So what we’re looking for is—we’re looking for Stage 2’s—who while they may be in a survival-based relationship—Stage 2/Stage 3—they actually can see that if they were thinking about it differently—that there’s actually a different, more powerful, and more effective way to think about the way that I work with people. At Stage 2, the way that people work with people is they work in a way where they’re disconnected. If I work in a way that I am profoundly connected to other people—and what I mean by profoundly is: you’re connected at the level of some sort of resonance of your values—then you’re more than: we’re not just manufacturing widgets here—this is an honest person who does things in a way that I admire and I want to work with that person.

ES: Right.

JK: I was working once in a utility years ago—they were very good at working with each other once they understood that they could drop the bravado and the machismo of Stage 3/Stage 2—and all of a sudden, they started working in a way that was uplifting to the company. I asked the class—I said: “I don’t know quite why I like working with you guys.” And this guy says, “I know why”—because he was one of the ones who was a leader in this area—and I said, “why is it, Tony?” And he said, “we cut square corners.” And it hit it right on the nail head for me. We like people who are honest, effective, generous, and they’re willing to work with other people, and it’s not based on their likes or dislikes, it’s based on their commitment to what it is that they’re doing together.

ES: Right. Now I want to further distinguish something. When you say someone at Stage 2, you don’t mean someone is inherently Stage 2, you mean they’re at Stage 2 in relationship to their environment.

JK: Yeah, that’s really a good and important point. The truth of it is there are tons of ways you can participate in life. You participate at work, you participate with certain people at work, you participate in your family, you participate maybe in your community—and you know—you may well be operating at Stage 4 in your community—think like maybe you’re a Scoutmaster or something like where you’re doing something for other people—and, at work, you’re maybe just surviving. And at Stage 2, it’s not uncommon for people to be in one of those stages and then to leave that stage and go somewhere else and then come back. And quite often, people don’t notice it and that is why I actually articulated the vocabulary. The vocabulary is very clear. As you speak, that will actually define the stage you’re in. And then if you take a look, a close look, [at] what your physical structure in relationship with others is: am I amongst the group and floating? That’s Stage 2. In effect: am I connected but I’m in a hub-and-spoke but I’m either the hub or the spoke? That’s a Stage 2/Stage 3 kind of relationship. Or am I in some sort of triangulated network kind of relationship where—wow this is kind of easy and we’re getting a lot done, and, we like each other, and, we’re enjoying the work because we’re doing it for some greater cause, some greater reason than just to turn out the work.

You take a look at championship teams. All the teams meet at the beginning of the season and they all decide whether they’re going to go to the Super Bowl. Are they going to win the Super Bowl? Are they going to make it to the playoffs this year? And in that meeting is where they actually design whether they’re going to be a Stage 2/3 team—which most teams are—or a Stage 4 team that occasionally rises to the occasion of Stage 5. In football, Stage 5 is winning the Super Bowl.

ES: Yeah.

JK: And by the way, teams meet in the Super Bowl competition—and when we get to the end of the competition—for one of them: “life is great”/Stage 5—and for the other “my life sucks”, which is Stage 2.

ES: The pitfall for some people when they first get introduced to the Tribal Leadership work is they hear the principles through an overarching context of the individual which your work is not really about. Right? So, I am Stage 2/I am Stage 3. Or—I need to use language in order to be Stage 4 so I’m going to use a lot of we language—there are all of those things that people could hear at the beginning which I think—and tell me if you think I’m wrong—but I think it’s shaped by the context of our society as a whole.

JK: Well, particularly around business, we live in a management-driven culture not a leadership-driven culture. And as a result, we often see that leadership is a subset of management, and, it’s not true. That’s backward. Leadership comes first and then management occurs afterward. Management Is granted by authority. If somebody tells me I’m the manager I come in, I go, Hi I’m your new manager. There’s no voting and we are now automatically put in a state of: I’m Stage 3 and you’re Stage 2 and I’m managing you. Leadership is granted by permission of those being led. So it’s a collaborative/cooperative kind of space. But you’re not going to collaborate/cooperate with me unless you are somewhat inspired by what I’m offering to you—as you know—what we’re going to be working on together. Management is pretty much saying the way things work is by domination, however, we’re going to make it a little nicer. B-schools teach people: oh what you need to do is you need to think about people, you need to take them into consideration, you need to listen to them. They give you all kinds of tips and all kinds of strategies so that you can get more out of these poor god-forsaken Stage 2’s.

ES: Yeah.

JK: But that’s not how it happens. How it happens is by having authentic relationships with people where there is authentic give-and-take in the relationship and where we are literally collaborating and cooperating with one another in order to get something done. That’s not the way we think when we’re in survival. When we’re in survival, we think about saving our own case and it doesn’t matter what happens. We have a point of view in the movie of our life because we’re not related to reality, we’re related to some kind of story that we’ve got going on in our life.

ES: Almost like a belief about your life?

JK: Belief—and it’s like a bad movie, Eric—like—I am the writer, producer, director, and star of the movie of my own life. And everybody else in my life is supporting cast, at best. So that means your mother, that means your mate, that means the people you work with—they’re there to support you—the hero in the movie I’ve called the life of Eric. And until we get that the life of Eric is actually a low-level sort of game that everybody is playing—I mean everybody is playing—until we understand that until I can actually combine my movie with your movie, and, a couple of other movies—and strip out the drama so that we can work together where we’re in a pragmatic realistic working relationship—we’re going to be inside of a whole bunch of people bumping up against each other doing nothing other than the movie of their own life and it’s a movie that really needs better writing, better directing, better producing, and better acting.

ES: Yeah. Can you explain the relationship between—in the personal development and and the consulting world, there’s a lot of emphasis on being in this peak performance state, on being in what they would call a flow state—can you explain the relationship between flow and Stage 4 and culture in general?

JK: Yeah. Stage 4 is a flow state. So, when we get it going, when we get everybody going, we’re in flow state. Well, what is flow state? Flow state is part of a cycle. There’s a four-part cycle and the first part of the cycle is something where we’re learning a whole lot, where it’s called loading and we are becoming overwhelmed with the information that we need and the adjustments we need in order to work effectively. So there is the learning part. Then, there is a formal part called the release. And the release is a place where maybe we do something socially together, we do something to kind of get away from what it is that we’ve been working on, and then coming back, what has happened is we have bonded in such a way that we go into flow. So if you think—I can look back and look at the military—so basic training was brutal. But after basic training, you got to a point where you really were able to kind of release the energy of all of that and bond with your buddies. And you came back—and you came back as: wow, we’re really bonded as a platoon—so it happens on every sort of level. A smart leader teaches, teaches, teaches, teaches, teaches—watches the frustration—and then at the right point—provides something quite often—it’s a place where they can laugh and they can have a good time and even poke fun at the person who is the leader—and then they come out of that and they are connected together and they go into flow. And flow—your productivity is just off-the-charts. People think flow is a place that feels good. It’s not [about] a place that feels good, and it might, but it’s not about feeling good. Flow is a place of accelerated learning. So what you’ve done is you have loaded up, you have got the release, you’re now working with the other people, and now you’re in a state of accelerated learning. You’re learning about what they can do, you’re learning about what you could do, and you’re applying the principles that you’re learning really fast. So accelerated learning leads to accelerated performance. And that gives us an access to the cycle of flow.

ES: There’s a model that you developed that actually breaks down that principle of flow. Can you talk about that a little bit?

JK: I’m not sure, tell me what you’re thinking of in this model—

ES: With the four quadrants.

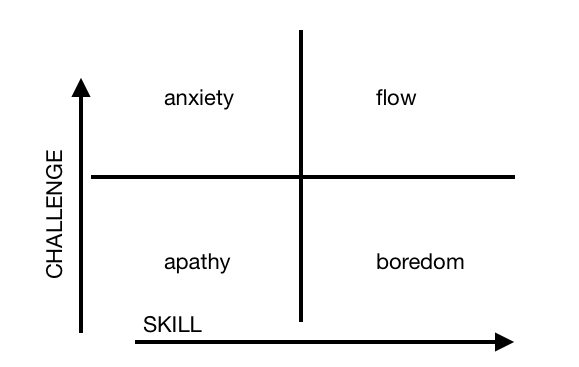

JK: Yes, well this is something that I developed for managers based on the work of Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi who is the guy who distinguished-out flow and he’s the genius who talks about it all the time. I’m just a guy who borrows from people smarter than I am. But if you look at a four stage matrix, and you look in the lower left corner, this is an area where you’re not performing well at all. So that’s an area of where it’s of low energy, it’s of low commitment. So nothing really happens here. There are two measures. One is the area that measures how difficult something is and your skill-set in being able to do it. The vertical access is how difficult things are. The horizontal axis is your skill-set. What it’s saying is low skill and low performance. However, quite often, we get people who are overwhelmed, they are in a state of anxiety, they are scared to death. If you take a look at it, you could see in the matrix that they’re in the upper left. And in the upper left there at a level of high expectation of their productivity. But if you look down on the horizontal axis you can see that their skill set is still very low. So, people who are are like that are in a state of overwhelm. And if you’re a smart manager, what you do is you provide training for those people so that they can actually do what it is their tasked to do. So if you give high training and high competitiveness, the productivity goes up immensely. If you take a look at the bottom right quadrant, this is a quadrant where people have an enormous amount of skill but they have very little incentive to do anything because they’re not challenged. So if you take a look at where the challenge is low and skillset is high, then they’re in a state of boredom. So the three states are:

low skill/low challenge: apathy

high challenge/low skill: anxiety or overwhelm

low challenge/high skill: boredom

[The fourth state would be flow. This is high skill/high challenge and would be in the upper right quadrant of the 4 stage matrix]

And where we want to get is where they’re in a state of high skill, and at the same time, high challenge. Flow—and there’s been an enormous amount of work done on this since 1991—I mean literally tens of thousands of case studies on this—where we find that if we want to get the best performance out of people, we’ve got to give them the highest skill set and the highest challenge and make it available to them.

This is why in sports—we say that you can take a look at what happened in some sports like track and field—you know 40 years ago—and we could see that the food is better, the actual activities that they’re doing is better understood, and so on like that. But ultimately, the coaching is better and the coaching is what has made—forget that they’ve got better shoes, and better surfaces to run on—all of that was going to happen with technology.

So technology is a part of it but the biggest part is that we have more aware coaches. We have people who are coaching who understand that: if I’m going to train and develop these world-class athletes, I have to get them into flow, and, the only way I could get them into flow is by high challenge and high skill set, and, so that’s what we work on.

ES: Yeah. Speaking of being action-oriented, one of the brilliant things about the Tribal Leadership work is that the principles are all applied, it’s not just theory and being intellectual about things.

JK: Yeah.

ES: And it only works when you actually apply it to situations. That leads me into strategy—and I know you have a strategy model that you developed.

JK: Yes.

ES: And I think it’s brilliant.

JK: Thank you.

ES: Any corporate strategist would tell you that strategy is very hard, there’s a very high rate of failure. Your strategy model has a very high success rate on average. One of the things that you figured out—which I think is incredible—is you saw the connection between taking on a strategy [and taking on a strategy] that was actually conducive to the culture that it was in. So if you have a team-based strategy in a Stage 2 culture, it’s not going to really work very well.

JK: Not at all, won’t work at all.

ES: Can you explain a little bit about—

JK: Here’s a little bit of my thinking about strategy. For one thing, I personally think that five year strategies are fine, two-to-five year strategies are fine. And I think that people should have an idea of where they’re going in two-to-five years. But I think that if you’re going to put that out as your strategy, you’re going to end up somewhat like [what] China does and Russia does with their five year plans because all kinds of things happen between here and the next five years including that we forget what we’re doing and we have to be driven to do it. So earthquakes occur, floods, famines, hurricanes, divorces, deaths, births, all these things are things that alter an individual’s strategy. So for myself, I began to just look at myself and I began to see: I can hold an idea powerfully for 90 to 120 days. So I thought to myself: I wonder what it would be like if I devised a strategy model that was only 90 to 120 days long. And then I re-strategized and I built a series of strategies on top of each other like people set pancakes on top of each other to get to the top one. But rather than going for what’s going to happen in five years, because it’s a lie, I’m going to go for: what can I do by the end of the quarter? So I like to set the strategies on a quarterly basis and then every quarter we visit them—even often during the quarter—to see how we’re doing on the particular strategy we’re working on. And at the end of the quarter, we have a report card day, and we set the strategy for what’s going to happen in the next quarter, and we go through the process again of visiting it, and doing what I call spin the plates during the course of the quarter. The strategy is simple. And, the strategy is simple because I was a strategist and I was failing as a strategist. I was doing the Blue Ribbon Strategy which is Michael Porter’s strategy from Harvard Business School. Michael Porter is a genius and he did put together a very complex and articulated strategy which ultimately became Singapore. You can’t say anything but good about Michael Porter and Porter’s strategy. However, I found that it was not practical for the individual, not practical for a lot of people, so I decided that I would go somewhere else to look for what would be my strategy. The trouble with Porter’s strategy is that it’s only successful 30% of the time and it requires a lot of tending to. And I thought to myself: we should be able to devise something that is more effective than 30% of the time. And I did. And in my searches, I found a strategy model that was simple [and] was effective about 80% of the time. And so I took that model and adapted it. At the time, it was not a strategy model that was useful for people. It was actually useful for moving heavy machinery around. It was a strategy that was used by the United States Army. I took that strategy—and over the course of about a year of working on it and proofing it on a beta group of about 300—roughly 12-year-old girls—like they’re the smartest people on the planet and they will tell you immediately and get immediate feedback whether this is working or not—and you will also be able to see: can they teach this strategy to others? The strategy is of no real value if you can’t not only implement the strategy but [aren’t able to] teach it to others so [that others] can implement the strategy for themselves.

The strategy model that we do is a simple. Basically, [a] Y-shaped strategy with 3 moving parts and three challenging questions. If you can unlock that strategy yourself, you will devise yourself a strategy for the next 90 days that is doable assuming you do it.

ES: Right. Now, have you noticed—so what I think is very interesting—one of the first experiences I had to being able to shift the environment around me wasn’t through Tribal Leadership—but then I started seeing all these connections—it was when I was doing a program through Landmark [referring to the personal training and development company, Landmark Worldwide, formerly Landmark Education]: The Self-expression and Leadership Program [commonly referred to as the SELP].

JK: Yes.

ES: And one of the distinctions I remember my program leader saying was that: your Self-expression is a function of the listening of your environment and that projects are an access to shifting that listening. Can you talk a little bit about how taking on projects can actually impact the Stage 4-ness, impact the amount of leadership versus management in a given environment?

JK: Sure. So first of all, that’s actually accurate and it’s a brilliant insight. The Self-Expression and Leadership Program actually is a senior part of the curriculum, which is called The Curriculum for Living for Landmark. The beginning of it is [The Landmark Forum], it’s all about you and getting you out of survival. Once you’ve done that, you go into the Advanced Course and you begin to see through the Advanced Course that your full Self-expression is going to be in the way that you interact with your communities.

And then you go into the SELP program, and in that, you design a project which does several things. It teaches you how to do projects. It shows you that if you can bring people into a project, and have it be a worthwhile project, something is going to bring a benefit, or in the language of that particular program, create a possibility for a group of people that you are touching—and the term that they say is touching, moving, and inspiring—that if you could do that one thing, what you will end up [having] out of that is a profoundly heightened sense of effectiveness. So there is lots to be said of the Self-Expression and Leadership Program in terms of your engagement with a project that gets you out of it—actually gets your nose out of your own navel—out of the way of your own Self—gets you into a conversation that is about designing effective and useful futures for other people, and as you do this, you will you will experience more success in your life.

One of the things I like about that program is that it’s about starting a program and that at a certain point of the program letting it go, just turning it over to the other people and going and finding another program. [In this sentence, John uses the word program instead of the word project]

Because you as a human being—see, in your case Eric, you’re a young man and I would guess that between now and when you die—if you live a normal lifetime—you will probably do 200 or 300 projects in your life. And one of the things that particular program does, and one of these things that I’m concerned about is: teaching people how to be effective and successful in doing whatever the projects are that they bring up. I’m a huge fan of the SELP program that Landmark provides.

ES: There was something else I wanted to ask you regarding survival. You said that—you talk about taking yourself out of survival, you have a term—and I don’t know if you’re the one that coined it or if you just use it—but you talk about the capital S Self versus the lower case self—and these two selves. Right?

JK: Yeah.

ES: Self, as an expression of who you are—and then this sort of this automatic identity—this kind of automatic machinery running in the background—

JK: Yeah.

ES: Can you go into how that plays into the environment that you’re in? If there is a correlation—

JK: Yeah, It’s the capital S Self. I think is something I came on—probably when I was about 17 or 18-years-old and I was reading Alan Watts—or it was that point in my life where I began to see that there was a difference between who identified myself as, what’s called my persona or the mask that I wear or constructed, or, what’s really at the heart of the matter for me as a human being.

And so that is what I call my capital S Self. The distinction that I like to look at is the difference between excellence and greatness because it gives me access to this. See, excellence is what other people say about you. You do something and you do it well and they say that is excellent. Excellence is something that is like a jacket that you put on, and, it looks excellent on you. Greatness is something that is deeply and profoundly inside of you, it’s not an external thing, like how you appear to the world. It’s actually your relationship to your inner—what I say capital S Self—and how do we nurture that?

Now both of those are going on all the time at the same time. And as a matter of fact, in the world of survival—to get back to your question—in the world of survival, mostly all we’re concerned with is:

How do we appear from the outside-in?

How do we appear to our peers?

How do we appear to our culture or community?

It’s all about, in the coinage of some people [in the Landmark community], it’s all about looking good—and people will sell their soul—I don’t think that’s much of a reach to say—people will sell their soul to look good. And when I say soul—you might want to say that people will sell out on their Self, they will sell out on their dreams, they will sell out on their values, they will sell out on the things that they truly stand for in the interest of looking good in other people’s eyes.

So when I say excellence versus greatness or when I say identity versus capital S Self, that’s just another way of how I look at it.

ES: Interesting. So I think that covers the models and principles in “Principles of Power” [here I am referring the models and principles that John developed specifically, not every single model and principle in the book].

Is there anything else that you think you’d like to add to this conversation or contribute to this conversation?

JK: Not so much. You know it’s kind of like—I had a friend say to me the other day, it’s not like eating an apple, it’s more like peeling an onion, and I like that. It’s kind of like as we talk about these things, and we’re sort of peeling it away, or peeling it away to see that which is underneath what that which is underneath—what is the source or the cause of something—and if you’ve eaten an apple all the way down, you’re left with a core. There’s something right there in the middle. But if you peel an onion all the way down, and you peel it all the way down, there’s nothing at the center. And nothing is your area, your soul, your Self, the place where you generate your creativity, the place where you access your true power. It’s never going to be outside-in. But outside-in is the way you’re going to always be perceived. It’s always going to be you as a human being and how you generate from the inside-out from nothing.

ES: That’s great. Well John, I really appreciate your time.

JK: Well, thank you. And, I appreciate the questions Eric. And I appreciate the opportunity to talk about something that I love a lot.