This piece was first posted on Substack. To comment, please go there.

Throughout the COVID lockdown, I often found myself listening to podcasts. In particular, I gravitated towards podcasts that helped ground the pandemic in historical and political context, providing perspective on an uncertain moment. As I listened, it struck me that, no matter what happened in the past—no matter how tumultuous an era, how disruptive a war or plague, how shocking a sudden turn of events—everything that has ever occurred, the immense variety of historical incident, ultimately becomes the same. Everything becomes a story.

This begs the question: what story will we tell about COVID-19? The events of the past year and a half were more than just a story of the emergence and behavior of a virus. It was also a story of the social, economic, scientific, and political context into which the virus emerged, and the intersection of these forces within complex, dynamic systems. Given this complexity, it can be difficult to predict which stories will rise to the surface of the overarching story of the pandemic. Yet it is important for us to try. The stories we tell about health shape how we engage with the present moment to support a better future—or how we fail to do so.

Consider the issue of race in America. For a long time, the story we told about race was distorted, incomplete, often serving to entrench systems of injustice in the present as we failed to come to grips with our history. This had consequences for the COVID moment, as racial health gaps, informed by this history, worsened the crisis. This reflects why the issue of stories is not merely an issue of how we curate our collective memory. It has deeply-felt implications for the present, shaping our capacity to build a healthier world.

With this in mind, this article will suggest four key narratives which emerged from the broader story of the pandemic and which have the potential to help define the overall COVID narrative in the years to come. This essay is the first of two parts. Having here addressed which stories we might remember, I will next week address the perhaps deeper issue of why we remember what we remember.

The first narrative which has come to define the COVID moment is that of scientific excellence. This is not to say it is the main narrative. I begin with it because it is what has enabled the stage of the pandemic we are currently in, with the virus waning in some parts of the world, even as it continues to rage in others. The speed with which a COVID vaccine was developed, supported by mRNA technology, reflects a new era in cutting-edge science. This narrative of scientific excellence is powerful for two key reasons. First, because this latest vaccine technology is indeed new and impressive, and has begun the long-awaited process of helping return us to our families, friends, colleagues, lives. Second, it is powerful because of how closely it aligns with how we already tend to think about health. We often think about health in terms of treatment—doctors and medicines—which can cure us when we are sick, rather than in terms of the structural forces in society which shape whether or not we get sick to begin with. We tend to confuse health (the state of not being sick) with healthcare (what we turn to once sickness strikes), which has led us to invest vast sums in healthcare at the expense of the core forces that shape health. The success of vaccines reflects that this investment is indeed core to supporting scientific excellence, but our story of health, and of COVID, is incomplete if it is confined to science and treatment alone.

This leads to the next core narrative of the pandemic, and arguably the central one—the presence of inequities. These include, centrally, inequities in morbidity and mortality, inequities in who bears the burden of the steps we have taken to mitigate the virus, and inequities in vaccine uptake. When COVID struck, it soon became clear that certain groups—such as Black Americans, people over 65, and people with underlying health conditions—were more vulnerable to the virus than others. This vulnerability was shaped by longstanding health inequities informed by marginalization, social and economic injustice, and other foundational forces in our society. The story of COVD is, in large part, the story of these forces. It is for this reason that the core argument of my upcoming book, The Contagion Next Time, is that preventing the next pandemic depends on our willingness to heed the lessons of this story and address these foundational forces. That Black Americans were twice as likely to die from COVID as white Americans, or that nursing homes and care facilities were uniquely vulnerable to the disease, are data that reflect challenges which predate the pandemic, pointing to the need to address the roots of these inequities.

These inequities have also come to define who has most felt the consequences of our efforts to mitigate the pandemic. COVID caused us to embrace extraordinary measures, shutting down society and incurring severe economic costs in the process. The pandemic led to significant job losses, which most affected low-income, minority workers. When the economy began to recover, with higher-wage workers bouncing back relatively quickly, lower-wage, minority workers recovered at a far slower rate. The effects of this inequity will likely be with us for some time, shaping the story of the pandemic and the lives of those who lived it.

Just as these inequities helped define the spread of COVID and our efforts to mitigate it, they also defined our efforts to vaccinate the population. Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director General of the World Health Organization, has said“Increasingly, we see a two-track pandemic: many countries still face an extremely dangerous situation, while some of those with the highest vaccination rates are starting to talk about ending restrictions.” The divide between these two tracks is deeply shaped by the socioeconomic conditions that determine vaccine access, allowing countries with greater resources to get the vaccine first, while less well-resourced countries wait. These factors also shape vaccine uptake in the US, creating the conditions for certain communities—in particular, communities of color—to lack access to vaccines, despite the disproportionately heavy burden of COVID and its economic costs many of them faced throughout the pandemic. The fact that we have the technological capacity to end the pandemic worldwide but are prevented from doing so by the features of that world—by all the ways it is not yet optimized for health—constitutes what is surely a key story of the pandemic.

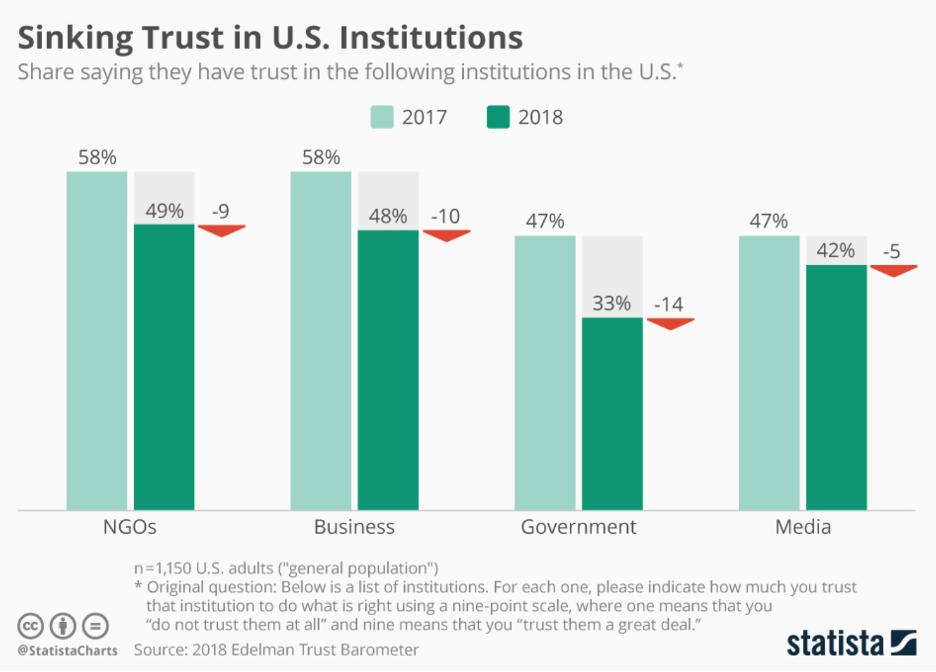

Third, the story of COVID would be incomplete without an honest reckoning with widespread loss of trust in institutions, and the consequences of this for public health. The most prominent example of this was how the inconsistent, often dishonest, words of former President Trump informed a lack of trust in guidance coming from the White House throughout the crisis. It is also true that seeming inconsistencies occasionally characterized the efforts of public health, perhaps most clearly in our field’s widespread embrace of civic protests last summer, in apparent contrast with our guidance on social distancing and masks. There is a case to be made, of course, that addressing the public health crisis of racism justified this temporary suspension of prudence. But it is still possible to see how our actions might seem contradictory, creating an impression among the general public that ideology may at times supplant public health’s commitment to the data. Given that COVID emerged at a time when trust in institutions was already declining (Figure), the story of the pandemic may well be, in large part, a story of how this trend accelerated, making it harder for anyone to speak with a widely-heeded, authoritative voice on matters core to health.

From Armstrong M. Sinking Trust in U.S. Institutions. Statista Web site. https://www.statista.com/chart/12620/sinking-trust-in-us-institutions/. Published January 22, 2018. Accessed June 23, 2021.

Finally, a core narrative of the pandemic, one which could well characterize our future memory of this time, is that, as bad as COVID was, it could have been far worse. I realize that this may seem strange, even unfeeling, in the context of mass death and suffering. But it is nevertheless true. COVID has been a disaster. Yet the virus itself, when compared to past pandemics, is nowhere near as lethal as it might have been. A future pandemic could combine the high transmissibility of COVID with the lethality of, say, SARS, or even of the Black Death. While the latter may seem historically remote, there is no reason why we could not see something as deadly strike in our own time. The better we understand this, the more the story we tell about COVID can help inform our efforts to build a world which is no longer vulnerable to contagion. Whether, in the future, we talk of COVID as a near-miss because we have finally built such a world or because we did not build it and are hit with a nightmare scenario, one which makes COVID seem like a mild trial run, will depend on what we do now, on the story we choose to embrace about what we have just been through.

Each of these stories represents a key part of the broader narrative of COVID. When we look back on this moment, it will likely be through the lens of scientific excellence, inequities, the erosion of trust in institutions, and how it all could have been fundamentally worse. It is also the case that one or two of these narratives may rise even further to the top of our minds, to define this era more conclusively. Only time will tell for sure what will happen. However, I would argue there are a number of factors which contribute to making stories “stick” when we think back on key events, and which increase the chance that the stories I have presented here will long outlast this moment. I will explore these factors, and how we come to believe what we believe in our narratives, next week.