Amid the deluge of bad news, there is still a case to be made for informed optimism. Taking the long view, it is an extraordinary moment to be alive, maybe the best in human history. This might sound crazy given the immense challenges we’re facing – whether the COVID-19 pandemic, the climate emergency or our bitterly polarized politics. But it’s easy to forget the many technological, social, economic and political revolutions that are reshaping our lives, mostly for the better. Despite recent setbacks, more people are living longer, healthier and wealthier lives than at any period since Homo Sapiens started their journey out of Africa 200,000 years ago.

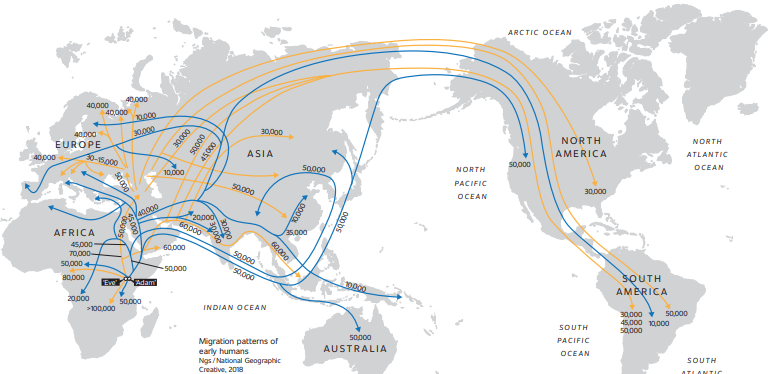

As explained in my new book with Ian Goldin – Terra Incognita: 100 Maps to Survive the Next 100 Years – maps can help make sense of the world around us. They are also one of our most incredible inventions. Think about it. For most of human history we had literally no idea where we were. What could not be directly observed was unknown. That started to change when our ancestors started painting their cave walls with the images of berry patches, herds of deer and natural springs. About 3,000 years ago, they started committing maps to paper, or rather papyrus. For the next few millennia they marked unexplored areas with fantastic and terrifying beasts – dragons, serpents and lions. Until recently, our planet (and progress) was virtually unknown.

Terra Incognita 2020

Today, maps are instrumental to guiding us toward greater understanding about the world and our place in it. High-resolution satellite maps are helping people predict everything from the onset of extreme weather events that threaten global trade or travel to the spread of dangerous crop infections that could destabilize food supplies. Maps are illuminating social and economic changes too, from how the world’s mega-cities are expanding to the volume of greenhouse gases they emit. In Terra Incognita, we show how maps infuse our everyday to the point where we forget they are even there. We use dozens of maps to explain some of the most extraordinary developments in human history.

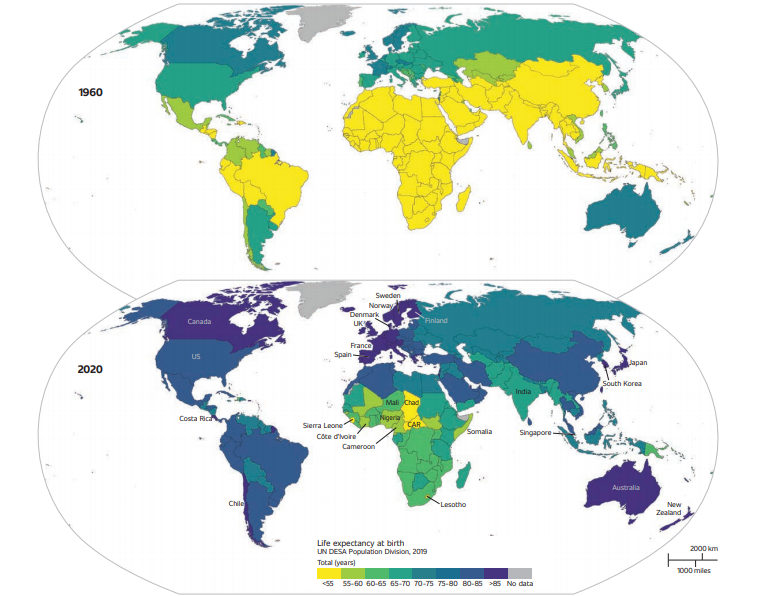

One of the top feel-good stories of the last few centuries relates to population health. Average life expectancy across the globe increased by a staggering 20 years in just the past five decades. It took from the Stone Age to the middle of the twentieth century to achieve similar improvements. It is easy to forget that for about 99.9% of our existence on this planet, humans were lucky to live more than 25 years. So, notwithstanding the grim toll of COVID-19 and the stubborn inequalities strafing our societies, most people are living longer and healthier lives than ever. This is not a call for complacency, but rather to re-frame today’s seemingly intractable challenges as solvable problems.

Terra Incognita 2020

To date, the oldest person who ever lived is a Frenchwoman named Jeanne Calment. She was purportedly born in 1875 and died in 1997 at the extraordinary age of 122 (and 164 days). Although her record is astonishing, it won’t last. Jeanne is a member of a super exclusive club: only a few thousand people have earned the distinction of being ‘super-centenarian’, living more than 110 years. By way of comparison, there are several hundred thousand centenarians – people over 100 – a disproportionately high number of whom are Japanese. While living more than 110 years is still an extremely rare event, soon lifespans such as Jeanne’s will not seem so special.

Depending on where they live, most people born in 2000 can expect to live for at least 100 years. Some scientists believe that human life could be extended by an order of magnitude longer. If you think this sounds like science fiction, you are not alone. For years, the accepted view was that we had reached the outer limits of human longevity. But this may soon be a minority opinion. A wave of new research led by biologists and gerontologists suggests that the maximum age may be much higher than earlier believed. Advances in technology, especially gene editing and regenerative medicine, means that average life expectancies could be elongated to 150 years by the end of this century. This of course raises enormous questions about the future of care, work, pensions and more.

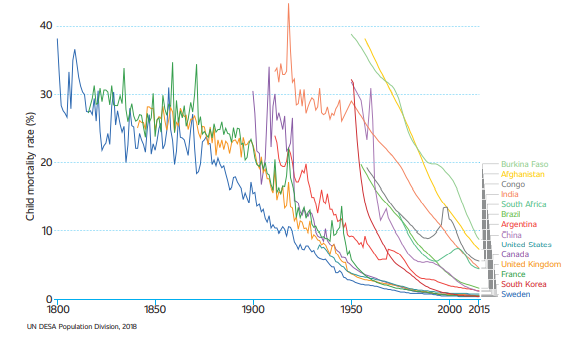

The reason so many of us are healthier and living longer – including in most developing countries – comes down to the spread of hygiene, nutrition, antibiotics and professionalized medicine. These innovations have helped beat back many of our mortal enemies, especially bacteria and disease. The spread of education and changes in mindsets about health were revolutionary. Straightforward and common-sense ideas – that smoking kills, universal vaccination is smart, national health systems can save lives – generated staggering improvements in population health. Maternal and child mortality plummeted in most parts of the world (though remains stubbornly high in some countries). And while viruses such as COVID-19 (and others) are a reminder of our vulnerabilities, we have come a long way in an incredibly short period of time.

Terra Incognita 2020

With or without a vaccine, COVID-19 will be with us for years to come. It could accelerate and deepen inequalities and global tensions. But the growing recognition of our vulnerability to infectious disease also represents an opportunity. Some governments, businesses and citizens are rethinking how to build back better – not only to improve health preparedness, but to make their communities greener and more inclusive. In Terra Incognita, we shine a light on how some of our remaining gaps can be closed and provide direction on how to truly realize our potential. The first order of business is not to succumb to cynicism, fatalism or despair. Instead, we should do what we’ve done in the past: mobilize our ingenuity and resources to achieve progress for the most people. This starts with educating ourselves about where the problems are most acute and mobilizing the best evidence to fix them.

In the COVID-19 era, there are low-hanging solutions for improving global health. Universal healthcare coverage is the most obvious way to reduce the gap in outcomes between and within countries and populations. The provision of basic hygiene and health care for infants, children and mothers – especially to those countries experiencing chronic disadvantages – is essential. Eradicating mosquito-born diseases – especially malaria, which infects almost 220 million people and kills 400,000 every year – would also help eradicate poverty and reduce ill-health in the poorest countries where it is endemic. Another goal must be to eliminate especially devastating diseases and viruses – and minimize the threat of superbugs. With help from groups such as the World Health Organization, the Global Vaccine Alliance, the Gates Foundation and others, we have done this before and we can do it again.