I wish I were an expert in something. Anything. In fact, I feel unqualified to write this article about giving advice on one’s career journey.

How can I guide anyone if I am nowhere near completing my own idealized career journey — achieving the role of VP of Engineering? In fact, my next career goal — Director of Technology — is still one or two promotions out of my grasp.

So what expertise can I provide? Fake it till you make it?

That’s like using the How To Draw An Owl meme to become an artist.

Step 1: Draw some circles.

Step 2: Draw the rest of the owl.

Even so, how do I pretend to be a paragon of success and impart any wisdoms to help others along their journeys?

I started my career as a fraud. I was an English and Film major who, to pay the bills, took a job writing news on this new-fangled thing called a website. When that B2B went bust along with all our other Dotcom Bubble buddies, some friends recommended me for our next foray onto Worldwide Web as their Webmaster. Because in their eyes, Web Content Editor and Webmaster were synonymous. And I needed the work. I relied on a couple Sys Admins to give me the basics of JavaScript, and I was on my way.

I finally got the confirmation of my fraudulence at Walt Disney Parks and Resorts online. Forget the part that I passed two interviews and had managers who put their trust in me. Instead, focus on the one Computer Science major who kept telling me what he learned in his database classes and his Java labs. And why my way of hacking CSS to compensate for the differences between Internet Explorer 5.5 and 6 wouldn’t work. My stock in this co-worker plummeted once he began routinely asking me for advice.

Any time I was in any conference room amongst other developers, I would feel equal parts elated and dismayed when I would hear one of these other more expert developers pitch the same idea roiling in my skull. My idea would work! Only, it was never my idea. Because I kept those to myself.

So how did I overcome this imposter syndrome? I didn’t. I concocted techniques over the years to manage my thoughts and perspectives that breathe life to these unproductive anxieties. While listening to Buddhist teachings and podcasts, imagine my surprise to discover that I, myself, have been a secular Buddhist for the past 20 years! My uneducated thoughts mirrored these “experts’” teachings. Even in expanding my thought process, I highlighted the error in my certainty that my experiential-based evolution was fallacious.

Socrates wrote, “The only true wisdom is in knowing you know nothing.” This truth became evident several years back during a time of financial anxiety. Not knowing how long it would take to sell our townhome was taking its toll on my sanity. Then, I discovered the liberating idea asking why my imagined worst-case scenarios took precedence over my imagined best-case scenarios. I realized that I didn’t have all the data, all the perspectives. Why would I believe my own thoughts without having the facts? I was jumping to conclusions and deciding only one outcome would be my future, and I actually knew nothing. It was a logical evolution to apply this lesson to every situation in my life.

Nature Abhors a Vacuum or an Open-Ended Question

I no longer feel the need to be the expert. My job is to support my team of engineers as they grow and become experts in the services and solutions we provide. My favorite technique in my arsenal of influence stems from my formative days.

As a self-taught developer — before Stack Overflow or even Google — I relied on Yahoo! searches to learn how to complete my tasks. I would often land on forum posts for similar queries, but most of these questions went unanswered. Those that had responses were full of vitriol and scorn.

These lengthy diatribes explaining why proposed solutions could never work was the genesis of an internet truth: “The best way to get the right answer on the internet is not to ask a question; it’s to post the wrong answer.”

Named after the inventor of the wiki, Cunningham’s Law has helped me quickly extract detailed answers in meetings. Colleagues now use this approach when asking “what do you think we should do” goes unanswered.

Open-ended questions and innumerable opportunities overload one’s sense of choices. Throwing engineers and architects my incorrect or incomplete version of a potential solution, idea, or definition gives them a starting point and a directional focus. And I get a more rapid, accurate answer. I sometimes even elicit deeper, more collaborative discussions by throwing out the less precise suggestion.

Skill vs Will

I have a friend fond of attributing underperformance to either lack of skill or lack of will. Lack of skill is a simple problem to remedy; lack of will, not so much. I prefer to take a more nuanced viewpoint.

My wife, a reading and language teacher. has spent her entire career helping students with a spectrum of learning challenges. Each student has had some barrier between their efforts and success. For some, it is a lack of commonality between their language of origin and English. For others, it is a processing issue like Dyslexia. Or distractibility because of external stimuli, such as allergic reactions.

Learning styles vary between everyone. Taking my wife as a role model has aided me in classifying the myriad of problems that affect struggling engineers. Some suffered from anxiety. I assisted one such engineer to better regulate his thoughts with walks around the block, asking him questions that appeared to not relate to the problem but in actuality helped him refocus the problem and made him take a different perspective on the solution.

Another engineer had trouble following a lengthy list of objectives. For this engineer, I used a technique my wife uses with students compensating for dyslexia and broke his tasks up into individual cards. This engineer’s productivity soon skyrocketed.

Some engineers lacked the shared language to better communicate with delivery managers. I emphasized keywords that I knew would help bridge the understanding between these two teams. Reiterating these keywords, be it technical- or delivery-based, recalibrated how these two teams communicated with each other and helped either team advocate for the other in status meetings.

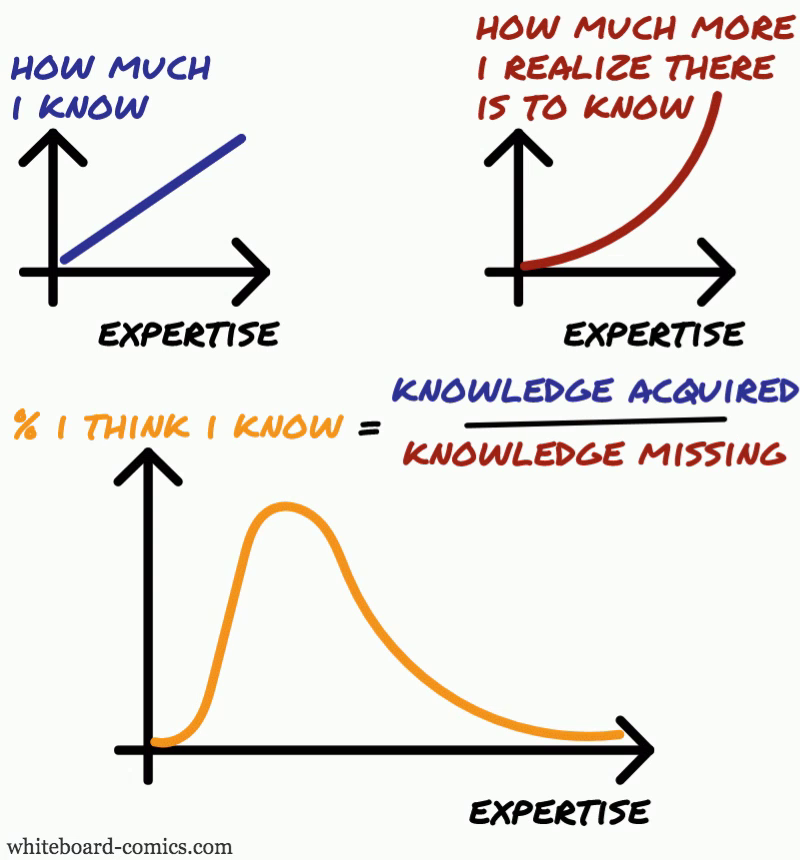

The only engineers I could not improve were certain they knew everything. Regretfully, these engineers could not keep up with their teams. They each were re-tasked, removed, or had to change career paths

Dunn-Dunn-Dunning–Kruger Effect

If Imposter Syndrome wrongly informs the suffering professional that his/her/their skills do not match his/her/their perception, then the Dunning–Kruger effect is the exact opposite but with more deleterious consequences.

One could argue that keeping an idea or thought to oneself harms the group — every idea should spawn conversation or provoke thought no matter how incomplete or uneducated. However, erroneously convincing or leading the team has more lasting consequences

Shivani Gopal wrote an excellent article breaking down Imposter Syndrome vs the Dunning-Kruger effect. I encourage you to read it.

Engineers suffering from the of Dunning–Kruger effect with whom I have encountered have always been a detriment to our team. These engineers have complained how the tasks required — combing log files for an error, learning new technologies, were beneath their skill sets or job descriptions.

Some would resort to bullying their peers, point out the flaws or weaknesses in the other teammate’s skills, or belittle engineers for commonplace oversights. The vitriolic engineers I’ve encountered inflated the feelings of the imposter syndrome in others on the team (myself included).

Nothing lasts forever

Often accompanying Imposter Syndrome, the feelings that anxiety and depression create are real and debilitating. But they are not reality.

I have a few silver bullet thoughts to get me through my own bouts of self-doubt, anxiety, and depression:

1) I don’t know everything

2) Nothing lasts forever

3) I can handle uncomfortable situations only when they have become a reality. Anything else is a made-up guess.

I have fallen in love with not knowing everything. We cling to ideas and desires that cause physical suffering in our minds and bodies. Racing thoughts, elevated pulse, tightness in our chests define anxiety. Yet the thoughts that cause this anxiety contain no truth in present reality. They are guesses. With practice, we can see through the non-reality veil of anxieties like Imposter Syndrome.

Waiting For The Other Shoe To Drop

Cherophobia is another fallacy that gives false credence to Imposter Syndrome. Translating as Fear of Happiness, this is the anxiety that something bad will soon follow good events.

Like other anxieties, cherophobia is not real; however, it is rooted in truth: Nothing lasts forever. Enjoy the times of peace because as events unfold, turbulence will occur. Appreciate the time of struggle, because that, too, shall pass.

Like every other skill we earn, following our thoughts, investigating the root of our anxieties, and having the confidence to accept that we are exactly where we need to be takes practice. I am nowhere near expert in this advice I am giving.

Ironically, I was certain my story will not relate or match anyone else’s path as I wrote this piece. I hope I am wrong. I love being wrong.