Recently, the Surgeon General sounded alarm bells over the growing crisis of teenage mental health. In the last decade, the rising number of teens struggling with feelings of helplessness, depression, and thoughts of suicide has alarmed parents and professionals. The pandemic seems to have accentuated this trend.

Meanwhile, adolescents are sleeping drastically less than the rest of us, and less than they ever have before. Shrinking sleep and deteriorating mental health are not a coincidence. Sleep deprivation creates a wear and tear on the brain and body, increases stress, makes kids prone to car accidents, increases risky behaviors, and exacerbates behavioral and health issues. To address teen wellbeing, we have to address sleep – there’s just no getting around it.

The crisis of adolescent sleep loss

The severity of the problem is stark: While the majority of younger kids get sufficient sleep, by middle school, they lose their grasp on good sleep and by the end of high school, only 5 percent of kids get adequate sleep on school nights. Teens need about 9 hours of sleep per night, but the average high schooler in the U.S. gets 6.5. That’s a jaw-dropping math problem, because 2.5 hours of missing sleep every night adds up to 12.5 hours of sleep loss by the end of the week. If this were a lab experiment, we’d end it, because it’s dangerous and inhumane. We know too much about how chronic sleep deprivation affects the brain and body.

How to fix the problem: systems and habits

To fix the problem, we have to change systems along with habits. Without changing the systems that support teens, they’ll always start the day with the deck stacked against them. High schools have to move start times to 8:30 a.m. or later, and limit homework so that teens don’t burn the candle at both ends. Sports coaches can schedule practices that don’t encroach on proper sleep. Sleep improves agility, endurance, and reaction time and makes high school athletes less injury prone – so this is a win-win. Technology companies should take responsibility for purposefully and aggressively stealing our kids’ attention (and sleep), by building in sleep-friendly components into social media and content platforms, especially those designed for kids.

What families can do

What can parents and teens do, at home, to improve sleep habits? Here are a few tips to get you started:

Teen self-motivation

No surprise to any of us parents: a teen has to feel motivated to get more sleep; otherwise it won’t happen. Teens themselves have to connect the dots between how they feel, what they care about, and how sleep will support this. Teenagers need us to lead with empathy, listen to their ideas and priorities, give them information, have family conversations about sleep, school, and schedules, and gradually hand over control of such things to them as they grow. Teenagers have to find their own motivation for sleeping well. No teenager wants to be told what to do, but in our experience, all teenagers like to feel healthy and happy.

If your teen isn’t interested in sleeping better, simply giving advice is rarely effective. Adolescents often take this as being lectured to, and their resistance can increase or they just tune out. Researchers have seen that for teens, hearing advice from a parent often triggers unspoken counterarguments in their minds. This doesn’t mean there’s no place for you to offer your thoughts or to give your teen information. It just means the ultimate goal is to help them identify their own motivation. Look for an in as an opportunity to talk about sleep based on something they care about or complain about. For example: “This math homework is so hard.” “My skin looks terrible.” “I keep getting injured.” You can also ask open-ended questions, imparting information in a way that is more helpful:

Instead of “Did you know that teens need nine to ten hours of sleep?”

Say, “Check out this one paragraph here.”

Instead of “Don’t you think you need more sleep?”

Say, “How do you feel about your sleep?”

Instead of “Do you think you need to go to bed earlier?”

Say, “What are your thoughts on when you go to bed and wake up?”

Instead of “You’re tired, I can tell. Go to bed.”

Say, “I saw you nodding off while we were watching a movie.”

Instead of “Is your phone distracting you and keeping you up?”

Say, “What do you notice about your devices and your sleep?”

Adopt Paleo-Sleep

Sleep is natural, but the modern world is not. The human brain and the sleep clock within are constantly confused by the signals of modern life, and misaligned with the cues of the natural world. Our sensory systems, and especially those of teenagers, become out of sync when signals of light and activity occur at the wrong times, and this creates very late bedtimes, sleep loss, and social jet lag. The beauty is that you can use this information to change your habits and bring yourself more in line with the natural environment. Working with our bodies’ natural sleep systems is what we call “paleo-sleep.” You cannot avoid modern life, but you can take control and manage it in a smart way that brings you more in sync with your natural sleep.

Harness the dark: lower the lights in your home two hours before your bedtime. In Heather’s home, the overhead lights all go off around 8:00 p.m. and only lamps remain (her teens don’t even notice, because our eyes adjust gradually).

Morning sun: Sunlight in the morning, even through the clouds on a winter day, is crucial to stimulating the internal clock and keeping our sleep systems in sync. Get 5-10 minutes of sunlight in the morning and after a couple of weeks, this helps your teen fall asleep easier at bedtime.

Resist the glorious sleep-in

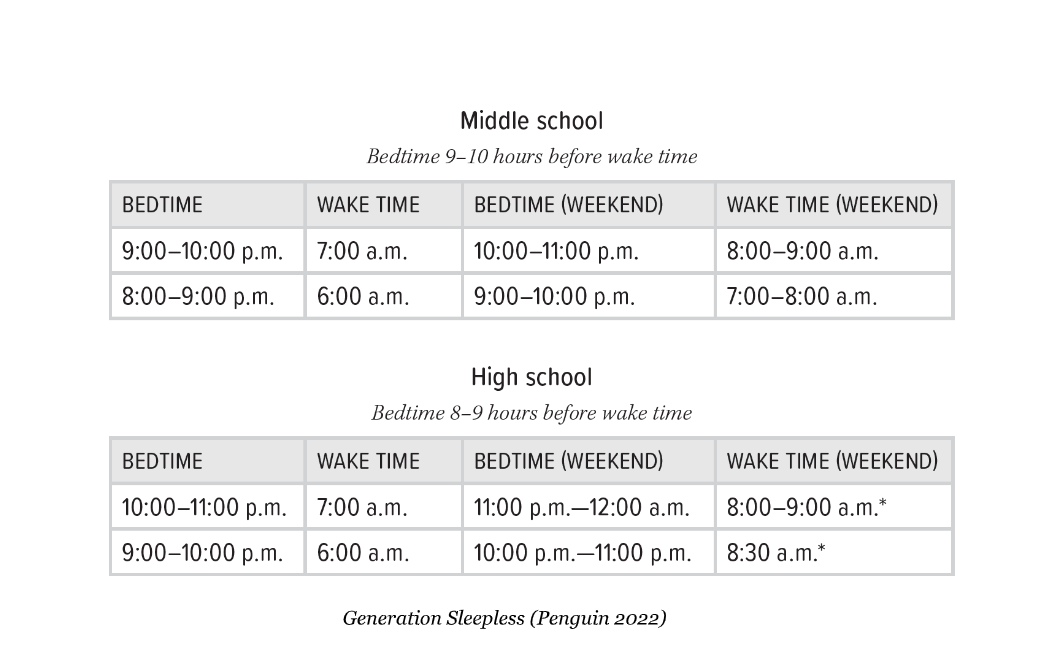

On the weekends and holidays, the temptation is to stay up late and make up for lost sleep by sleeping in, but when we lean into this too much, it exacerbates social jet lag and also makes the transition to Monday morning extra hard. As luxurious as sleeping in on a Saturday morning can feel, if we take it too far, it comes back to steal our sleep later on. On weekends, since very few high school students have gold-standard sleep during the week, the best approach is to split the difference, sleeping in some, but not so much as to confuse the body clock. For most kids in middle and early high school, one hour past their usual wake time is enough to enjoy the benefits of a full night’s sleep, without going too far off the weekday schedule. If your teen has an extreme schedule that requires significant sleep deprivation during the week (we can’t ignore the reality for some high schoolers with very early classes and mountains of responsibilities), then he might need to sleep one or two hours later on the weekends.

Keeping wake-up times regular on the weekends and school breaks and getting five to ten minutes of sunlight in the morning are extremely helpful for keeping your brain in sync and falling asleep at bedtime.

Here’s a good example of schedules for teens:

Adolescence is a stage of life when proper sleep is vital and game changing—to a degree that few of us fully appreciate. Books on baby sleep are stacked high on our bedside tables, because no one doubts the importance of sleep to a growing baby. But the truth is, a teenager’s brain is going through an equally important stage of growth (with potentially more life-altering and consequential outcomes). Adolescence is an awe-inspiring and pivotal developmental phase, when the brain undergoes massive reorganization and growth, and much of that vital work happens during sleep. Missing sleep raises the risk of mental health issues, heightens teen stress at a neurochemical level, makes athletes more accident prone, and causes the brain’s memory storage to malfunction, which short-circuits learning and academic success. When sleep is missing, the ripple effects on mental and physical health are tremendous and exponential.