April is Autism Awareness Month and there is much to celebrate. Every year, we see an increased understanding and acceptance of what it means to be on the Autism spectrum. Public and private schools have made great strides in supporting students with special needs. However, despite the progress we’ve seen, some of our most vulnerable students are experiencing trauma in a place where they should feel safest: classrooms.

To be clear, teachers, aides, and other personnel are not at fault. They are simply using the tools on which they have been trained or what they know exists. Unfortunately, those tools are outdated and ineffective. I’ll get to that shortly, but let me begin by describing the challenge.

The Challenge

Data shows that children with disabilities, including Autism, are disproportionately physically restrained and secluded each year as a means of punishment or behavior control. During the 2015-16 school year, an estimated 122,000 students were restrained or secluded in the country’s public schools, according to the U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights. Of those students, children with disabilities represented 71 percent of those restrained and 66 percent of those secluded.

To complicate matters, a 2019 report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office revealed that the federal restraint and seclusion data is likely to be under reported, so those numbers could be significantly higher. An investigative report by ProPublica and NPR found that children are restrained or secluded over 267,000 times each year in U.S. public schools, and – despite representing only 12% of the public school population – students with disabilities comprise two-thirds of the children who are physically restrained or secluded from their classmates annually.

Restraint and seclusion are practices meant to contain individuals who are at risk of harming themselves or others. However, research indicates that these types of interventions actually cause, reinforce, and maintain aggression and violence. When a child is restrained or placed in a seclusion room, it can cause them to act out even more, fueling a cycle of trauma.

Cause for Hope

Again, I am by no means placing blame. Teachers don’t want to use these techniques, but when fear and frustration take over, they believe they have no other alternative but to “force” children into physical or emotional submission. As someone who has worked in behavioral healthcare for 30 years, I was in this same position myself many times early on in my career. And I know that educators are simply using the tools they know to get through a crisis situation. Based on my own experience and the evolution of the organization where I work, as well as many others with which I now work, I’m here to tell you there’s a better way.

At Ukeru Systems, we are training teachers how to offer a safe, physical alternative to restraint and seclusion. We rely on a trauma-informed approach to create an environment of Comfort vs. Control® by utilizing patented blocking pads to de-escalate conflicts. We rolled out this system at Ukeru’s parent organization, Grafton Integrated Health Network—a Virginia-based nonprofit serving children and adults with Autism and co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses—and the results speak for themselves.

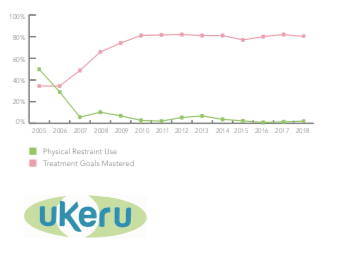

In 2003, Grafton was restraining the 220 individuals it served over 6,600 times a year and using seclusion upwards of 1,500 times. Traditional crisis management methods were failing patients and contributing to a staff turnover rate of 54 percent. We knew something had to be done, but we couldn’t find a program that provided a safe alternative to seclusion and restraint – so we decided to develop our own.

Within a decade, we reduced the use of restraints by more than 99 percent, completely eliminated seclusion, and reduced staff turnover by more than 64 percent. The number of client and caregiver injuries also plummeted. From a business perspective, the Ukeru method has saved Grafton over $19 million since 2004, including $2.5 million in annual workers’ compensation insurance premiums.

I’m happy to report Grafton’s experience is not an anomaly. More schools are recognizing that restraint and seclusion should be an unacceptable form of behavior modification, especially for children with Autism and other disabilities. So far, Ukeru has helped more than 210 schools and organizations across the U.S. and Canada provide a physical alternative to restraint and seclusion.

For example, in South Carolina, the Berkeley County School District reduced its use of restraints by 45 percent within 10 months of adopting the Ukeru method. And, in Pennsylvania, the Millcreek Township School District brought its number of annual restraints from 47 to zero. Millcreek’s Special Education Supervisor, Kate Barbaro, told us their teachers were skeptical at first, but the results ultimately won them over.

“There is arguably nothing worse than having to call parents and tell them that you had to put your hands on their child; that there may be red marks or bruising,” said Kate. “We had no student or staff injuries in the year we implemented Ukeru. Our staff is mostly pleased to have an alternative to restraint that works.”

I am grateful for how far we’ve come to support individuals with Autism, but there is still more work to be done. Let’s not forget that kids with Autism grow up to be adults with Autism. If teachers, schools, and healthcare providers step up to support these children today, society will be better for it tomorrow.