Download

I first learned about artist Alexandra Grant through a panel discussion at Jack Rutberg Gallery of Fine Arts in April 2013, which is a gallery I was introduced to by Marcia Reines Josephy, the former director of the old Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust.

When I then heard about Alexandra’s project Forêt Intérieure/Interior Forest at 18th Street Arts Center, I was immediately hooked and became one of her participants. I always had a thing for French culture and literature. I loved the French language and used to play Chopin waltzes and Debussy’s Arabesque and Reverie. Besides, I grew up in a literary town in Germany, the neighborhoods of Friedrich Schiller, Hermann Hesse and Eduard Moerike with a father who binges on books.

Part of my education in Germany consisted of having to read the works of German writers, but the problem in high-school was that I had my own interpretation of literature. I didn’t want to just look at literature from the point of view of the teacher. I was a young woman with a vivid imagination and a unique life experience with a desire to look at the work of a creative person through her own pair of eyes. That’s why I was fascinated by Alexandra’s participatory project, because of our shared love for the written word and the French language, but also because of her free and creative approach to literature. The French author Hélène Cixous had asked her to create a work based on the concepts of her book Philippines, which is a combination of reverie, autobiographical memory, and an imaginative re-creation, centering around Peter Ibbetson, a novel by Georges du Maurier, in which two childhood friends are separated by fate and then reunite as adults through a shared dream-life. Maurier’s novel is about love, as many literary works, but a love that’s less talked about. It is the kind of love in which one isn’t together in real life but through fantasy and dreams. Hence the love in the novel is symbolic and could stand for the shared emotions a piece of music, a work of literature, a film or a painting evokes. In a way, it’s an artistic spiritual kinship. Alexandra came up with a forest as a place for shared imagination and collaboration. We helped her to create that forest.

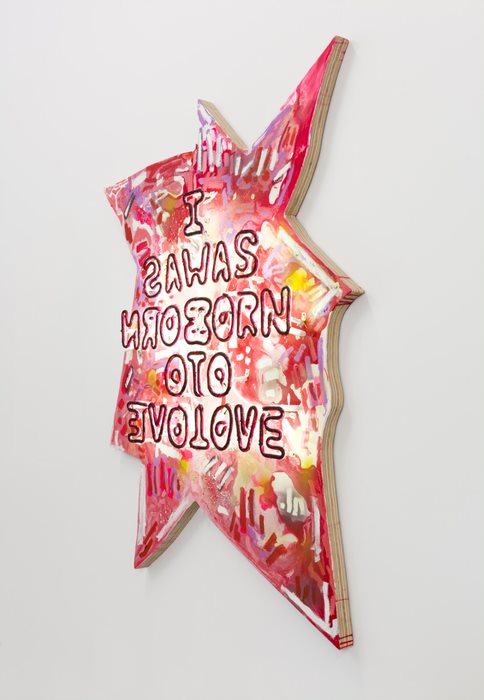

I then noticed that in Alexandra’s following works the theme of love occurred again. This time, however, it no longer was just a part of a bigger concept, this time it seemed it had turned into the essence of her work. She created her series Antigone 3000 and Born to Love, and did another participatory project titled Antigone is you, is me at the Archer School of Girls in Brentwood, California. The three projects are inspired by Antigone, one of the three Theban plays by the ancient Greek playwright Sophocles, which explores the struggle between man’s law versus god’s law and contain a line from the play, in which Oedipus’ daughter Antigone takes a stand against King Creon, the strict ruler of Thebes, who denies her brother Polyneices, a proper burial, because he attacked Thebes, a city his brother Eteocles wanted to rule alone. Since this was an offense against the gods, which would have hindered Polyneices to have an afterlife in which Antigone’s soul and his soul could have rejoined again, Antigone sacrifices her life for the love to her brother. Hence, Antigone took a stand against something she believed to be wrong, at a time, where women had no saying in society. Her courage turns her into a heroine. Therefore, in Grant’s Antigone inspired works one will find an important line from the play, which was slightly altered from “I was born to join in love, not hate—that is my nature” to “I was born to love, not to hate”, presented in her typical reversed or mirrored language, integrated in her abstractions.

Once again, I felt intrigued. Hence, when I received an invitation to Alexandra Grant’s show at Lowell Ryan Projects with the catchy title “Born to Love”, I immediately RSVP’d. The theme of love just seemed so appropriate at a time, in which people’s lives are destroyed through an unfair immigration system, and in which more and more people are acting out and killing others due to overpopulation, isolation, social envy and other reasons, and in which human relationships suffer, because of technology, careers, competition, a lack of respect and inequality.

In order to understand Grant’s work better, I then read about Sophocles’ trilogy and the entire Antigone. A new whole world opened up to me. There was poor Oedipus who was suffering from the crime his father Laius committed. He gets abandoned as a child and is left on a mountainside to die with his ankles pierced. He then commits a horrific crime, as the curse predicted. He kills his father Laius in self-defense and marries his mother Jocasta without knowing these were his parents. Subsequently, he has four children with Jocasta, which are Antigone, Ismene, Eteocles, and Polyneikes. Yet, instead of forgiving himself, because the curse was out of his control, Oedipus took all the blame and blinds himself as a form of self-punishment. Due to the curse, he has to live the rest of his life with the shame and guilt for murder and incest and gets mistreated by his sons as well. And so, what I took out of Sophokles plays is that certain things are already predetermined by fate and that we often carry the burden of our ancestors, but that regardless we shouldn’t hate ourselves nor others, but to keep walking on the path of love. For it is love that in the end will win over all the unfairness created by man.

Grant’s latest works, which recall Glenn Ligon’s Double America, and are currently hanging in the backroom of Lowell Ryan Projects, use this key phrase from Antigone again. Yet, in contrast to her previous works, in which the phrase is sometimes presented openly and at other times hidden by splashes of paint or prominent straight lines which scatter in all directions, her newest creations, present the phrase through neon lights, mounted on top of two unevenly shaped wood. Hence, this time, her words are standing out spatially and are in the viewer’s face. One can’t escape them. The one is covered in red tones, the other in blues. And if one looks closer, the shapes of the wood are similar to cut-out cookies, perhaps Christmas cookies, and the straight lines, she used for contrast, which can be interpreted as the human law, are suddenly less dominant and seem to be painted by hand without a ruler. To me, they appear like sugar sprinkles.

And since it’s the end of the year, and soon Christmas decorations will illuminate the towns and numerous fireworks appear on the sky, I see her new works as carriers of a message, perhaps a Christmas wish or New Year’s wish, or both. Hence the wish for a more humane society, in which there are more equality and compassion. A wish for an upcoming new year, the year 2020, in which not hate, but love shall reign. And if that’s not what Alexandra intended to say through her work, and I completely misinterpreted her art, then this is also okay, so let me be the one wishing it for us. And I just hope she’ll forgive me.

Lowell Ryan Projects

4851 West Adams Blvd.

Los Angeles, CA 90016

+1 323 998 0063

https://www.lowellryanprojects.com/

Alexandra Grant