There is no doubt that black Americans face more stressors in their daily lives, in general, than many other racial groups. This is not just because they have less control over and access to financial resources, due to generations of inequality, but also because of the constant structural, social, and psychological violence of racism and general discrimination.

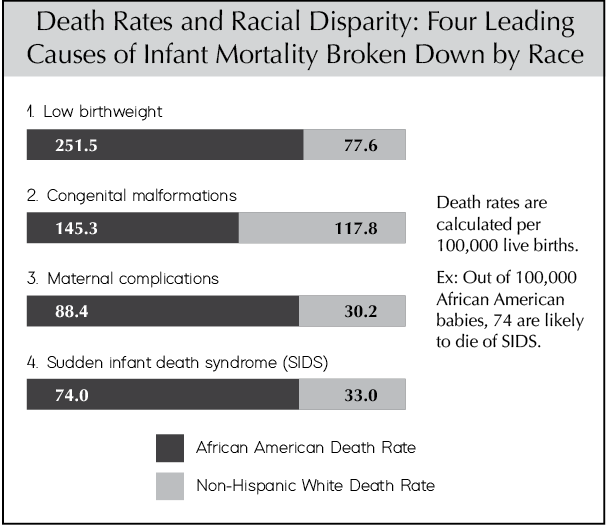

SUID rates generally parallel increases in degrees of racism, poverty, and marginalization, especially in urban locales and amongst indigenous peoples like Native Americans. However, these effects are not felt equally across minority groups. Because indigenous peoples and black Americans, in particular, face more severe socio-cultural and economic marginalization, almost all studies show negative impacts on the health and well-being of people in these groups. This includes significant increases in infant illness and mortality before issues of sleeping arrangements are even considered.

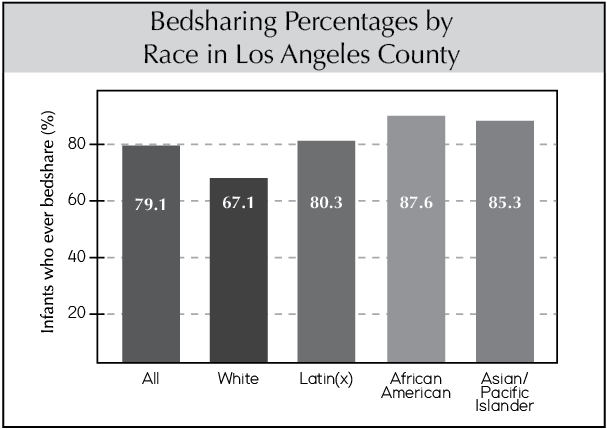

A survey in a 2005 issue of Pediatrics found that the prevalence of bedsharing among black children was five times that of white children in the U.S. While black families top the bedsharing charts, Asian and Hispanic households also report higher rates of bedsharing than white households (1). Although black American families experience higher-than-average SUID and SIDS rates, Asian and Hispanic households experience lower-than-average SUID and SIDS rates, meaning that bedsharing is not the deciding issue.

Local media stories about bedsharing deaths rarely, if ever, probe into the larger social context. This context includes the high percentage of black babies born prematurely (a risk factor for SIDS) and the existence of other risk factors that are almost always associated with bedsharing deaths in these communities. For example, in the U.S., black mothers initiate breastfeeding at about a 20% lower rate than white mothers. Yet again, before sleeping arrangement even comes into the picture, these babies are at an increased risk of dying. For poor black families living in large cities such as Chicago, Cleveland, the District of Columbia, and St. Louis, the impact of these risk factors is even more pronounced. It is not surprising that where black Americans live in the greatest poverty, the highest numbers of infant deaths attributed to bedsharing take place (2, 3).

Low breastfeeding rates, in particular, contribute significantly to the likelihood of infant death. A study published by Dr. Renata Forste (4) found that breastfeeding accounts for racial differences in infant mortality “at least as well as low birth weight does.” She and her colleagues write: “Breastfed infants are 80% less likely to die before [one year of age] than those who never breastfed, even controlling for low birthweight,” and, “For every 100 deaths in the formula-fed group, there were 20 deaths in the breastfed group…the formula group with 100 deaths had five times as many deaths, or a 500% increase in mortality.” This is truly an extraordinary statistic that calls on local and national health institutions to lead campaigns promoting breastfeeding, especially in black communities, as stridently as they have driven the anti-bedsharing campaign.

Research has shown that there is a link between living in poverty and high rates of infant deaths. These deaths are not just due to the risks of formula-feeding, but also due to other contextual factors, including other children sleeping next to the infant, bedsharing in a small or cramped bed, the bed being placed close to a wall or furniture where a baby can get stuck, sleeping with an unrelated adult male partner in the bed, and low birthweight. All of these amount to a less stable and safe sleep environment. Unfortunately, medical and civil authorities have not been willing to tackle the social reasons why negative outcomes are associated with bedsharing in these populations or why SIDS rates can be predicted by zip code. Poorer communities have a disproportionate number of bedsharing deaths compared to white and other sub-groups practicing the same sleeping arrangement.

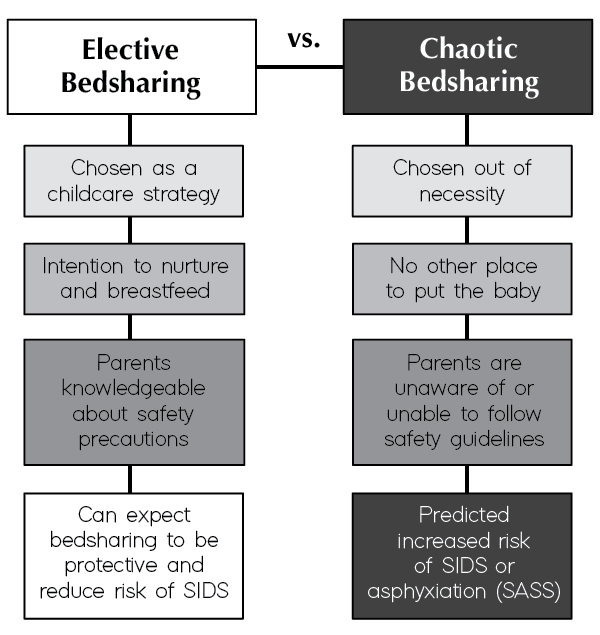

Keep in mind that there is a significant difference between elective and chaotic bedsharing. Elective bedsharing, what I am recommending and advocating for, is when parents make an informed decision to bedshare for the purpose of nurturing and breastfeeding, and are knowledgeable about the risk factors and how to avoid them. In this scenario, we can expect that bedsharing will reduce the risk of SIDS.

Chaotic bedsharing, on the other hand, is when bedsharing is practiced out of necessity rather than as an intentional parenting technique. In this case, parents sleep with their infants because they feel they have no choice due to circumstances like a lack of beds or cribs in the house, the presence of rodents, or numerous other factors. Families who practice chaotic bedsharing also tend to be less knowledgeable of SIDS or SASS risk factors, such as smoking, drugs, alcohol, unsafe beds, or having other children in the bed with an infant.

Unfortunately, poverty and its associated stressors are more likely to cause families living under these conditions to practice chaotic bedsharing, leading to relatively higher numbers of bedsharing deaths compared to elective bedsharing families (typically from higher socioeconomic groups). It’s a sad fact that socioeconomic struggles can affect the safety of your child as he or she sleeps, but that is not to say that the environment can’t be made safe for lower socioeconomic families through proper education and recommendations from healthcare providers.

For the healthcare providers in question, when choosing to support or not support a family’s sleeping arrangment, it’s important that the family’s intentions and general circumstances are considered. In many cases, the problem is not bedsharing, but rather the manner in which it is practiced.

Again, I have to stress that it is a tragedy that such disparities exist between and within groups of people living in the same country, whether it is bedsharing, prematurity, or the birth of underweight infants that accounts for up to 40% of black births. However, using statistics derived from families in low socioeconomic situations to make conclusions about all bedsharing is inappropriate. Instead, this data points to the need to address the perils afflicting poor households directly. This may include simply working harder to share the critical importance of breastfeeding during prenatal care visits with pregnant black mothers. For many reasons that we will explore in Chapter 6, simply choosing to breastfeed greatly increases the safety of bedsharing, reducing risk of injury or suffocation (5).

1. Lahr, M.B., Rosenberg, K.D., & Laipidus, J.A. (2005). Bedsharing and maternal smoking in a population-based survey of new mothers. Pediatrics, 116(4), e530-42.

2. McKenna, J.J. (2002). Breastfeeding and Bedsharing: Still Useful (and Important) After All These Years. Mothering Magazine, 114, 28–37.

3. Blabey, M.H. & Gessner, B.D. (2009). Infant bed-sharing practices and associated risk factors among births and infant deaths in Alaska. Public Health Rep, 124(4), 527–534.

4. Forste, R., Weiss, J., & Lippincott, E. (2001). The decision to breastfeed in the United States: does race matter? Pediatrics, 108(2), 291–6.

5. Nelson, E.A., et al. (2001). International Child Care Study: Infant Sleeping Environment. Early Human Development, 62(1), 43–55.