In the dozen years since undergoing a pair of brain surgeries, Tara MacInnes became a reliable resource for others with her condition – the roughly 1-in-100,000 who have moyamoya disease, a disorder caused by blocked collateral arteries near the base of the brain.

Her devotion is evident in her email address. It starts with “moyamoyadvocate@”

Yet for all the unsolicited emails Tara received from fellow survivors, she rarely sent any.

Then came the night in January 2017 when she found herself in an emotional rut.

Needing a mood-lifter, she asked Google to find her a story of a “Coast Guard” “cancer survivor.” (Joining the Coast Guard was a childhood dream ruined by her disease.)

Facing too many options, she switched to “Coast Guard” “brain surgery.” Same problem.

Being a stroke survivor herself – a result of the moyamoya disease – Tara refined her search to “Coast Guard” “stroke survivor.” Up popped stories mostly about the same guy: Sean Bretz.

Sean had been several years into his Coast Guard career when an aneurysm burst in his brain. He couldn’t talk or walk for about six months. The stories she read and videos she watched showed the progress of his journey to his current status: fully recovered, he’s a physical therapist assistant at a facility where he was once a patient. Better still, he too was involved in stroke-related advocacy work.

Tara sent Sean a friend request on Facebook, then went to bed. He saw it before work the next morning and accepted. She responded with a short note.

She pondered how her message would be received. She hoped he greeted it with the warmth and appreciation she’d detected in everything she saw the night before.

Sean indeed was comfortable with people reaching out. As he considered replying, he thought, “I’ve got nothing to lose.”

Another thought: “She’s very cute.”

May is American Stroke Month, making this a great time to tell the story of these two people who overcame strokes at young ages – Sean’s ordeal at 23; Tara’s strokes occurring when she was 5 or younger, and her surgeries at 17.

A better reason is that on May 4, they were married.

As soon as they were engaged, Tara and Sean knew they’d walk down the aisle the first Saturday of Stroke Month. As a bonus, World Moyamoya Day was two days later.

The charming story of how they met and their cross-country courtship – her in San Antonio, him in Savannah, Georgia – is delightful. You can read a detailed version here. But for the rest of this telling, let’s put the spotlight back on Tara and everything she’s done for the stroke and moyamoya communities. And we’ll start with her showing what survivors can accomplish.

Before her brain surgeries, Tara was a varsity swimmer and varsity water polo player in high school in San Jose, California. It was part of her preparation for that dream job in the Coast Guard – as a rescue swimmer.

After her surgeries, Tara was recruited to become part of the inaugural swim team at Grand Canyon University.

“It was a bit of, `Take that, moyamoya! Take that, stroke! I’m going to regain a part of my life that I didn’t think was possible,’” she said.

Her next feat was swimming from Alcatraz Island to San Francisco. A few months later, she swam the choppy waters beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, south end to north end.

Then she rose above the water. Way above.

“I went skydiving from 15,000 feet,” she said.

Through it all, she was consumed by a constant thought: “This is me chasing after things I never got to do in the manner that I envisioned and dreamed of doing.”

That’s how she replaced the adrenaline jolt she would’ve gotten from being a Coast Guard rescue swimmer.

But there was another void created by the dashing of that dream. She needed a new career path.

After two years at San Jose State and a year at Grand Canyon, her search continued at Our Lady of the Lake College in Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Tara was considering nursing when her dad suggested she become a counselor. What seemed like a surprise to her made perfect sense to him. Because it’s what she’d already been doing through her work with stroke survivors, especially moyamoya patients.

Tara was treated at the Stanford Moyamoya Center, which is both one of the nation’s top facilities for the condition and only a half-hour from her parents’ home. Tara and her mom knew many families came from far away to be treated there and didn’t have a local support system, so they became exactly that for about 40 families. Tara also became a regular at the center’s annual summer picnic-reunion, a tradition she continues.

Tara went on to get a master’s in clinical mental health counseling. She moved to San Antonio to begin her career. She sought extra hours to earn her state license more quickly, and several people recommended she pick up shifts at the VA hospital.

Extra work and a military connection? It seemed perfect.

Then Tara learned the VA hospital only hired people with a similar-but-different certification than hers. That was the disappointment that sent her to Google in search of a mood-lifter on that fateful evening in January 2017.

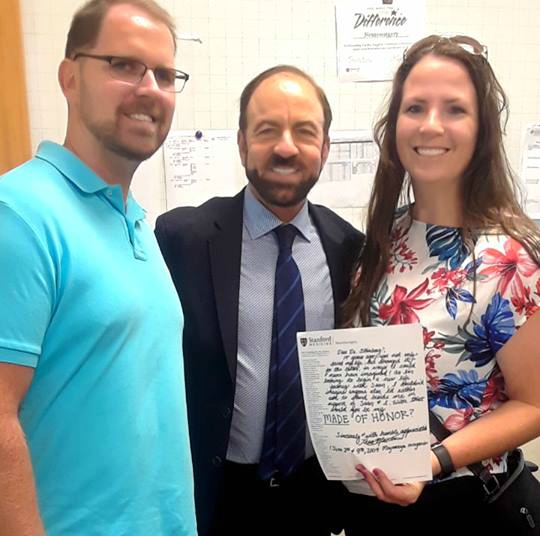

One more nifty connection involves Sean’s proposal. He did it at her parents’ house while her family gathered to attend the annual summer picnic-reunion at the Stanford Moyamoya Center.

Following their wedding in San Antonio, Tara moved to Savannah. She and Sean are excited to live under the same roof, along with their four dogs. The couple also looks forward to doing advocacy work together.

Tara, meanwhile, has one more bucket-list item in mind.

Before the stroke, she dreamed of swimming the English Channel by herself. Her modified goal is to do it as part of a relay.

“With Sean piloting the support boat,” she said.