How author Jane Howard inspired a career and a life.

Clearing out closets in preparation for a move, I sat on the floor tearing pages out of my old writers’ notebooks and detaching the wire spirals, before recycling them.

But I held back a fistful of pages from a steno pad dated 1996, the year I earned my MFA in Literary Nonfiction from Columbia University. This list caught my eye:

Jane Howard’s Legacy:

- Enjoy mango milkshakes every chance you get

- Have a hymn for everything

- Edit in green

- Enjoy food, music, poetry

- Bring a bathing suit wherever you go, for just in case

- Break bread with whoever you meet

- Choose your own family—and make it a big one while you’re at it

- Even if you’re dying (especially if you’re dying) dance, sing

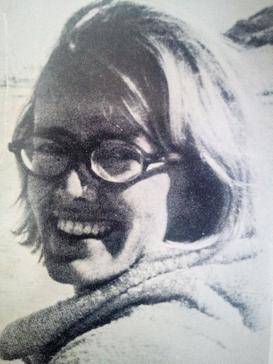

Jane Howard was my mentor and I was her research assistant in the mid ’90s when I was studying at Columbia, and until her death at age 61 in 1996. She was best-known for her biography of Margaret Mead, but my favorite of her books was A Different Woman, a folksy, rambling survey of early 1970s feminism. The title suited Jane as well. Born in 1935, she never married, and never had children. She had a career as a journalist writing for LIFE magazine, and was also a professor at Yale, the University of Georgia, and, of course, Columbia.

I admired her for all of that, but I really loved her rules for creating a unique life as an independent, intellectual, and fun-loving woman.

As Jane’s assistant I spent hours in her apartment talking over her latest writing project, often with a mango milkshake in hand. I remember opening a closet door in the kitchen, on which there was a list for what the housekeeper should do:

Fold laundry, put away laundry, dust books and shelves, clean cat litter.

Clean cat litter? There was no cat, and no sign that any had been in residence in the recent past.

Later, when Jane was very ill with cancer, I found a prayer notice tacked above her fax machine that had been given to her by her housekeeper. Apparently, a congregation in Spanish Harlem was praying for Jane, who according to the obituary which would later run in the New York Times, was raised as a Congregationalist—though she found spirituality in nature, not church.

But evidently she accepted prayers from all comers. Perhaps especially from her housekeeper, whose voice I heard one morning after Jane had been hospitalized, speaking in halting English on her answering machine saying, “Jane, I like you. I like you very much.”

I liked Jane very much, too. I liked that she was the type of woman to wear green sneakers and trousers because she liked green, and for no better reason. I liked that her eyeglasses were reliably smudged and dirty, because it told me she had more important things on her mind than keeping things tidy. Outer appearances were beside the point with her, it seemed.

Although I studied under her to learn the craft of literary nonfiction, ultimately Jane’s prescriptions for living a good life inspired me to write my first self-help book. (I am now the author of three books in that genre.)

I didn’t know Jane for long, but her legacy lives on in me. Not only do I edit my my students’ (and my own) papers in green ink, I keep a bathing suit in the trunk of my car all year long … for just in case, and I treasure my large, chosen family. I haven’t had many mango milkshakes since leaving New York shortly after she died, but ever since meeting Jane I have been making my own lists for living a beautiful and meaningful life–and doing my best to stick with it.