Learning to live, love, and thrive together

There’s an old piece of wisdom that advises us to establish relationships with people who challenge us. Doing so can be incredibly difficult — particularly for the long term — but by pursuing the ability to navigate through such challenges, we are engaging in nothing less than the journey of self-acceptance. The rewards are profound, often unexpected, and lifelong.

For the past two decades, I have lived with a partner diagnosed with Complex PTSD (or C-PTSD). This type of post-traumatic stress disorder comes from repetitive trauma rather than a single instance or a series of isolated instances.

Repetitive trauma, especially over a long period of time, strips the sense of safety, trust, and well-being from an individual and leaves a raw wound that doesn’t quite heal. People affected by recurring trauma can instantly return to heightened anxiety, fear, hurt, or anger when instances carrying flavors or reminders of past trauma arise.

In general, C-PTSD is much more common in American society than many recognize. It stems from extended childhood abuse, institutional oppression, imprisonment, bigotry, and poverty-based violence. It wears the mask of bipolar disorder, multiple personality disorder, schizophrenia, and myriad other diagnoses. Many people walk around with volatile emotions spilling out into their lives without knowing why, and still others do their best to drown them out with distractions.

That’s not to say that all “difficult” people have C-PTSD; rather, it’s to acknowledge that unresolved past trauma is a major and prevalent teratogen (aggravator) of challenging behavior.

Forming a lasting relationship with someone affected by past trauma means you will invariably come face to face with their emotional wounds (whether they want you to or not). It probably won’t be when you expect it, and it may happen frequently. If you aren’t solid in your own foundation, it can shake you to your core (as it has often shaken me). But if you are willing and able to endure it, if you can open your heart “once” more (again and again), the bounty of unconditional love is yours to claim.

When I was little, I remember hearing an African folktale about a lion with a thorn in its paw and a mouse that pulled it out. I loved the idea that a tiny mouse was not only brave enough to approach a roaring, angry lion when no one else would, but it was astute enough to see that the lion was hurt and compassionate enough to remove the thorn from its paw.

One of the most important pieces of consideration to keep in mind when dealing with a “difficult” person is to see if you can identify if there is a thorn in their paw. Regardless of what the thorn is, if there is a source causing them hurt, their behavior is reflective of that rather than their direct relationship with you (excepting those situations when you are the direct cause of hurt).

Using this method will help you learn to recognize a good person who is hurt rather than a bad person (i.e. someone who maliciously derives pleasure from the pain of others).

To relate this to “real life,” the mornings are the most turbulent part of my partner’s day. This is due to recurring instances in his youth when he was awakened abruptly in situations of high danger that necessitated his complete awareness and preparedness.

As he explained it to me recently, he wakes up feeling “old” and gets younger as the day goes on. In other words, he feels the intensity and the burden of life first thing in the morning (particularly when elements of it are still continuing in the world at large), and gradually becomes more “lighthearted” as his healthy coping mechanisms settle in.

In the morning, the thorn in his paw is sharp and painful, and even though we both know it is there, it still hurts as freshly as ever. He roars sometimes, causing all the creatures in the jungle to run away. As the day goes on and we talk and bond, the immediacy of the pain lessens.

The thorn never goes away, but by acknowledging it and the pain it causes, we can walk forward together, one step at a time.

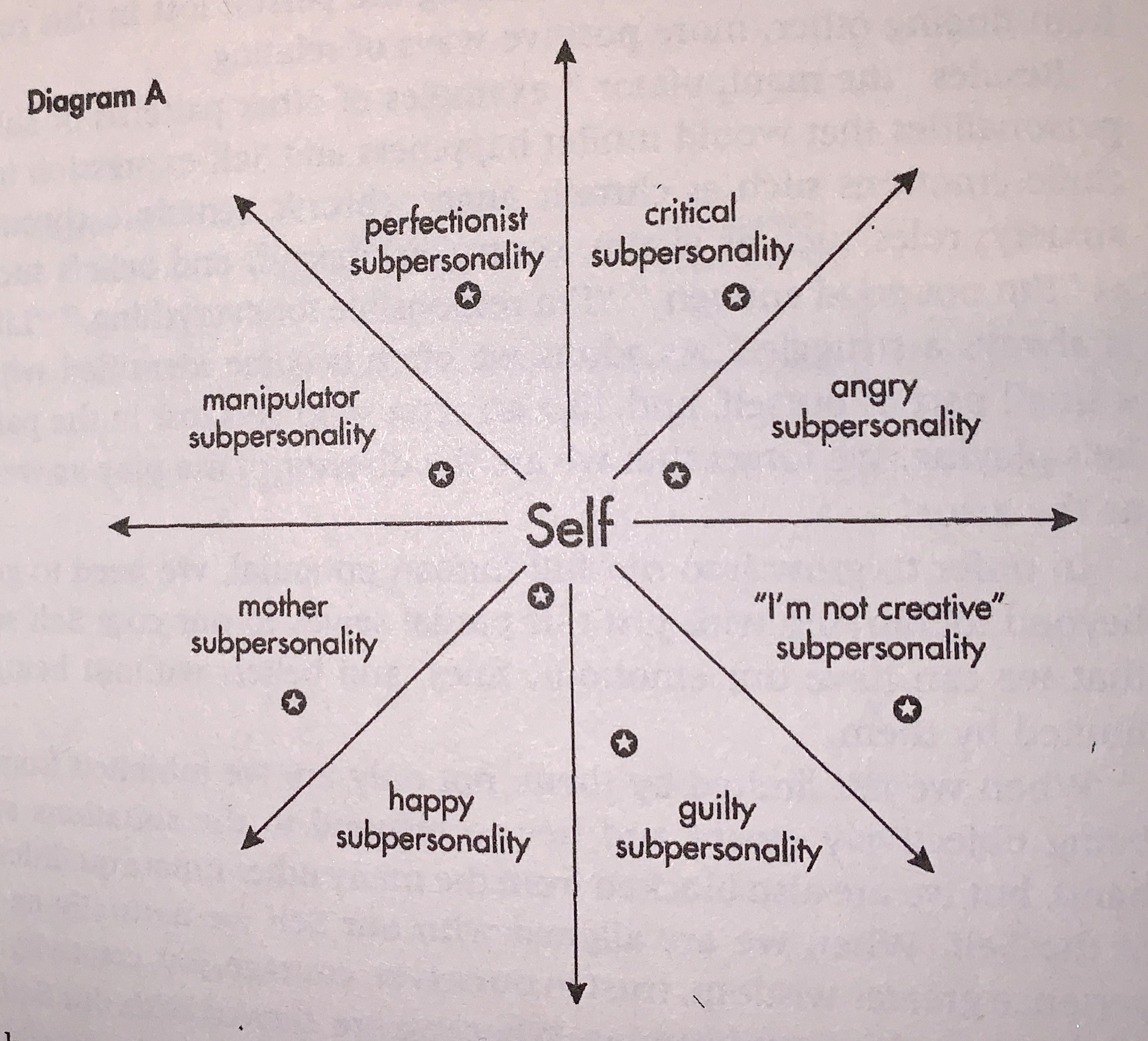

Knowing the effects that different stimuli prompt in our behavior is a valuable tool in interacting with and building a relationship with anyone, including ourselves. It doesn’t matter if its trauma, societal expectations, or imposed archetypes: we can diverge from our truest, most pure Self for a myriad of reasons.

When you are interacting with someone, you can focus on their center Self to get the best measure of them as an individual. Doing so requires looking past their surface selves, a feat accomplished by determining what caused the surface self to emerge.

By acknowledging and accepting the surface self of another (and what causes its manifestation), you can help light the way back to their center Self. You can open the door for their own Self-acceptance and remove the turbulence of disconnection. You can help dissolve the thorn each day, until its constant removal becomes the fact rather than its constant presence.

Just as our brains myelinize the neural pathways we use the most often, our conscious self can learn to quickly return to its center Self through the building of deliberate pathways that become familiar through reuse. We can learn to ease our own thorns and those of others.

Hold the same standard of acceptance for your selfs and you will build a steady foundation from which you can interact with the world in your fullest, most aware capacity. Know what causes you to become decentered — to want to roar — and acknowledge those causes as valid but manageable factors. Identify your Self and foster your connections back to it as much as you can.

In this way, the process of learning to see and love “difficult people” is one of seeing and loving your own Self. That is the greatest gift we can receive and exchange in our journey through life.