It’s mid-afternoon on a Tuesday. I’m wearing pajamas and sitting on my couch with my tuxedo cat buried deep in my lap—not a typical day for an internal medicine intern. It’s March in Boston, and outside my window there is heavy snow falling, high winds howling, and large trucks plowing. On this blizzard day, I somehow manage to be scheduled to the only shift in residency that is non-essential. With only three patients of moderate acuity at the Veteran’s Association (VA) intensive care unit, my long call team has offered me the day off.

You might guess that I’m feeling overjoyed at the opportunity to sleep in, watch television, and stuff myself with leftover birthday cake. I am indeed contemplating these activities, but elation does not exactly describe my current emotion. I felt clogged with panic.

My co-residents are completing their afternoon tasks on patients I cared for yesterday, including an eighty-nine-year-old who will likely pass away during this storm. My fiancé is in the hospital serving an oncology service and won’t be home until later in the evening—if he can even make it through the snow. Our second-year residency schedule was just released, placing my first rotation as a supervising resident in the scariest place in the hospital—the cardiac intensive care unit. I am already feeling unprepared for that dreaded moment and am lamenting that today will be a day without learning and practice. I just don’t feel like I deserve this day off.

This feeling is not unfamiliar to me. Sometimes I call it guilt, sometimes anxiety. It has been around me and inside me for some time. As a thirteen-year-old, for an English assignment in which I was asked to describe my superstitions, I described it as “an evil cloud, living right below my ribs sending vibes out everywhere.” It is the feeling that something is just not quite right. In clinical terms, it is my depression. And medical school was the first time I named it as such.

My depression is episodic—sometimes fleeting, and sometimes hanging on for days or weeks. While it has been smoldering within me since childhood, medical training gave it the ground to blossom. When I entered medical school, I hopped onto that conveyer belt that doesn’t stop moving, doesn’t tolerate weakness or hesitancy, and doesn’t allow space for grieving or loss. And with that momentum, I lost the ability to care for myself in the ways that I needed.

I hit my low when I took a year off for research and I was no longer frantically filling each moment of my day with a check box. It surfaced when I had a chance to sit down and read fiction, a moment to learn a new recipe, and the time to think up a hobby. It was the first time in years that I was forced to face myself—rather than focusing on the tasks ahead of me in the next hour, and the steps ahead of me in the next years.

I spent many hours crying and finding fault with myself. At my worst moments, I hit my temples with the palms of hands and fantasized about the sharp blade of the kitchen knife. I was a bad daughter, a bad partner—and someday I would be a bad mother. While I had once known I would be a good doctor, I now questioned this notion immensely. I had entered a career path where good was never good enough. And I was surrounded by people too tired to care for themselves, much less give me the immense reassurance I suddenly needed from everyone around me that I was going to be ok.

This was my secret life. Outside my home and my relationship, I put on a show. I presented myself as competent and energetic, and boasted a sarcastic but compassionate sense of humor. I ran the student wellness group, and spoke publicly about the risky intersections of mental health and medical school. My goal was for no one to imagine that I was in a dark place myself. And thus, I perpetuated the stigma that everyone entering medicine confronts on those days in which they just can’t muster being perfect.

I sought help. I leaned on a therapist for weekly consultation. I started a medication that helped me weather the ups and downs. I leaned on a small group of friends from whom I kept nothing. And I relied on my partner, whose patience and love were tested every day. Day-by-day, the darker moments got shorter. I anticipated the plummets and learned to call them out before they consumed me. And while I believe I have recovered from my worst symptoms, I imagine my depression will always lurk within me. When my world quiets down, it finds a path to resurface—like a potential space whose physiology is as predictable as a beating heart.

These days in residency, each moment is filled with one, two, or three tasks at a time. I write my notes while on hold. While my patient shares extraneous details, I check his labs at his bedside. While I put in orders, I eat my lunch and respond to a nurse’s concern behind me without even turning my head. Yet when there are seconds to spare, I am often filled with the dread that I am missing something, that I’ve made a mistake that will harm my patients, or that I am somehow letting down my peers around me. Because even when the task in front of me is literally impossible, I am expected to complete it. To ask for help is demoralizing. To admit I need a moment of rest or recuperation, unthinkable.

I will never know if my fear of a snow day would have emerged if I had not become a doctor. However, I do know that medicine imbeds self-doubt into even the most confident, pessimism into the most positive, and worry into the care-free. I know that medical training has taken far too many young lives, whose exhaustion and sense of inadequacy grew too great to bear. And I know that despite my daily decision to trudge on, I too am not immune to contemplating the tempting relief of escaping it all.

Since writing this piece in 2017, Katherine has finished residency, is a proud new mother and will be starting work as a hospitalist this fall. She continues to ask for help when she needs it, and encourages other students and residents to do the same

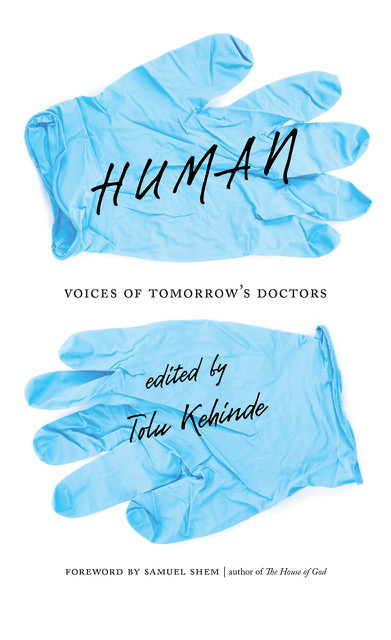

This essay appears in Human: Voices of Tomorrow’s Doctors, published on September 15, 2019, and available through Dartmouth College Press distributed by Chicago Distribution Center.

Follow us here and subscribe here for all the latest news on how you can keep Thriving.

Stay up to date or catch-up on all our podcasts with Arianna Huffington here.